Antarctic Microbial Mats: A Research Dive At Minus 20 Degrees Air Temperature

Lake Fryxell is located in the McMurdo Dry Valley on the Antarctic mainland. The lake is covered year round with four to five metres of ice, and it has some special biological features.

At the end of 2025, this is precisely where Elisa Merz, a biogeochemist from the University of Konstanz, worked from a field camp with her international colleagues. Every day, after breakfast and a meeting in the only heated hut, the team of researchers headed out to the dive hole.

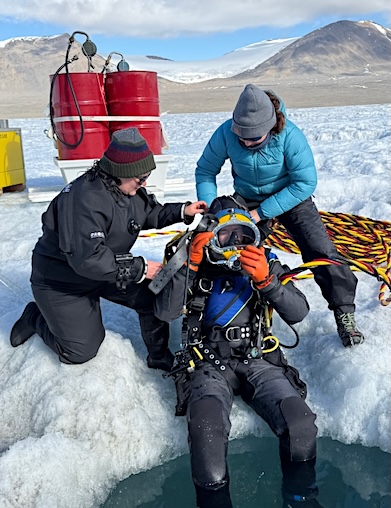

Preparation for the dive. © Marisol Juarez Rivera

The water in Lake Fryxell only contains oxygen at depths of up to about ten metres – but not any deeper. Such anoxic conditions are usually only found in places like the deep ocean or in very deep parts of inland lakes, such as Lake Constance, at depths of 50, 70 or 100 metres, which is deeper than divers usually descend.

Ten metres, by contrast, is a very manageable depth for divers. “Lake Fryxell is also special because it does not contain any macrozoobenthic organisms – no fish and no large algae – but a whole lot of microorganisms”, Merz explains. This makes it a research paradise for her: “The total ice cover means the lake is not exposed to wind and has no currents – thus it does not mix, either.

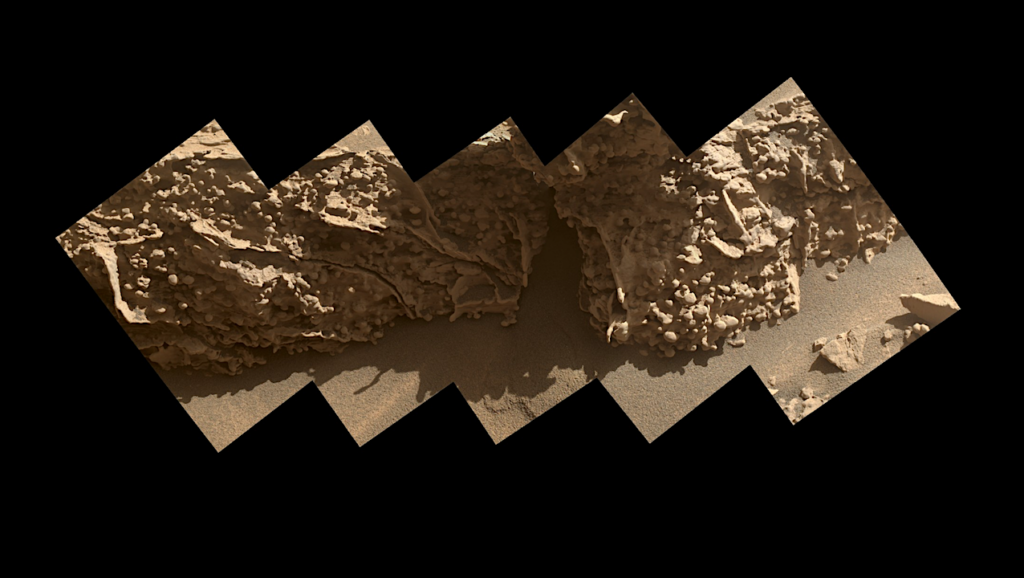

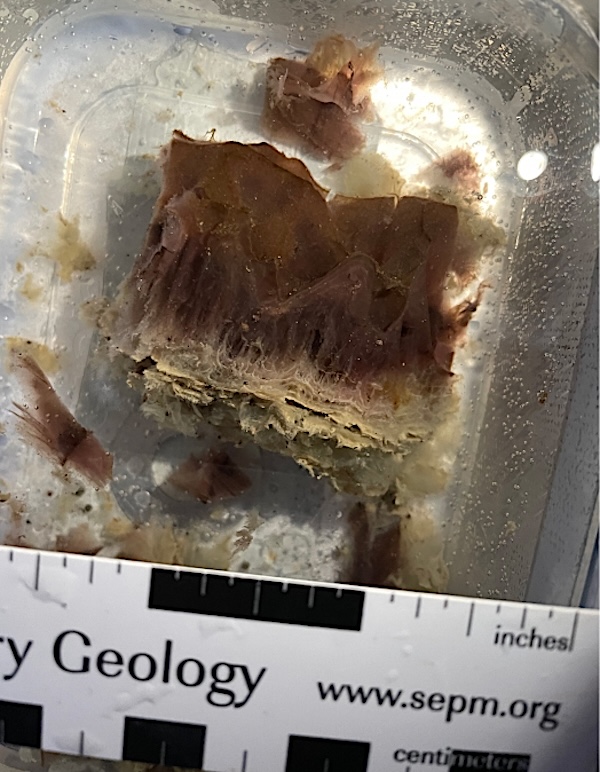

Microbial mat taken from Lake Fryxell.© Marisol Juarez Rivera

As a result, we can see microbial mats at the bottom of the lake especially well. These are colonies of microorganisms that appear layered, like lasagne.”

Diving when it is minus 20 degrees outside? “That seems incredibly cold, but the water we dive in is actually four degrees – a little bit warmer.” The hardest job, according to Merz, is being in charge of holding the diving umbilical (the line supplying divers from the surface).

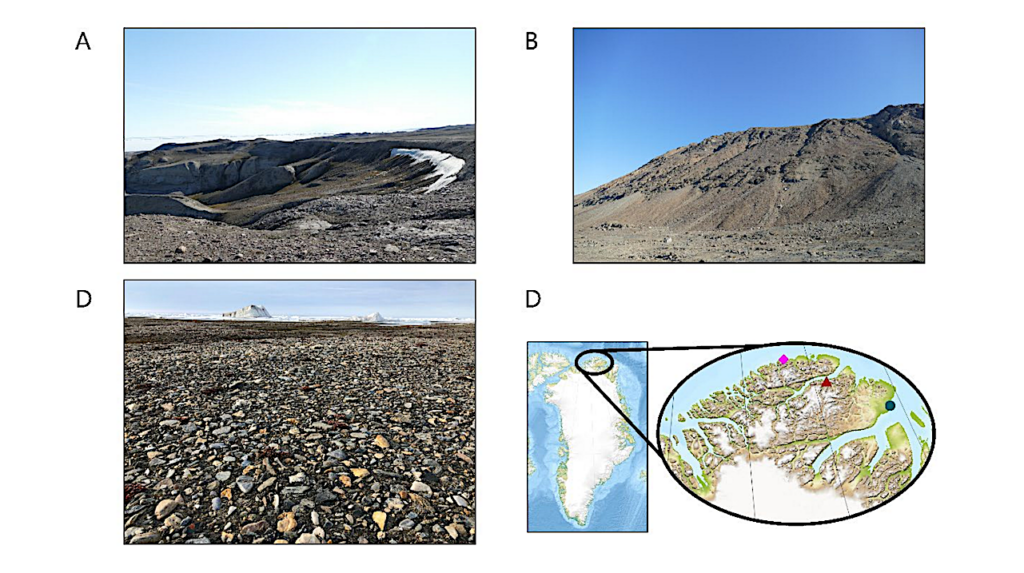

The field camp at Lake Fryxell. © Elisa Merz

This person feeds out or pulls in the line as necessary and keeps direct contact with the diver – all while standing in front of the tent and being directly exposed to the wind and cold. “Although we do take turns, 45 minutes of standing outside is really the absolute limit”, the microbiologist says.

What is it like to stay at the US’ McMurdo Station – the largest research station in Antarctica? How are the research conditions in the field camp at Lake Fryxell? And what does Elisa Merz study there? Read more in the in-depth report “In her element” from the University of Konstanz’s online magazine.

Astrobiology,