Keith Cowing’s Devon Island Journal – 15 July 2007: Surreal Landscapes and Late Evening Thoughts

Leroy Chiao, Matt Reyes and I went out for a traverse today. Our traveling companions were Pascal Lee, the PI of the Haughton-Mars Project (who led the traverse), Jarloo Kiguktak an advisor and field officer for the HMP 2007 field campaign, and his son, Joseph Atchealak.

(L to R) Matt Reyes, Keith Cowing, and Leroy Chiao in front of the inukshuk built to honor Michael Anderson — Keith Cowing

We were making both a survey and a tour of the various research points of interest in and around Haughton Crater. Our mode of transport: ATVs, the workhorse vehicle of the arctic.

After filling up our ATVs at the fuel depot, we headed for Anderson Pass just north of Base Camp. After several kilometers of travel across the remains of an ancient lake – now named von Braun Planitia, we arrived at our first location.

Inukshuk built to honor Columbia astronaut Michael Anderson in 2003 — Keith Cowing

The last time I was here was back in 2003 when we built an inukshuk to honor astronaut Michael Anderson. Over the course of several months inukshuks were established across Devon Island for all of Columbia’s crew.

Inukshuks are human-like figures made out of free stone. Some are rough pillars; others have a definite human shape to them. The Inuit use such structures as markers on their landscape. Properly constructed, as was this one, they can last for centuries.

As part of our visit to Devon Island this year, Leroy, Matt and I, local Inuit boys, and members of the Haughton Mars Project Research Station family will build an inukshuk to honor the crew of Space Shuttle Challenger.

The site we chose is an obvious one. When viewed from Base camp you can just make out the inukshuk on the horizon atop one of two small rises. When you look at these two rises on the horizon you cannot but help being reminded of the “Twin Peaks” which are prominent features at the Mars Pathfinder landing site.

It was odd to return to this place. When I was last here – almost 4 years to the day – the weather was cold and it was blowing snow. Today, while it was cool, the sky was bright and filled with immense, dramatic clouds that had been dragged into vast sweeping shapes by high altitude winds.

This time I was also returning with someone who actually knew Michael Anderson as a living, breathing co-worker. For those of us who were here to build the inukshuk in 2003, he was only someone we knew from post-accident stories about his life.

After pausing at the Anderson inukshuk we walked over to the adjoining rise where we were thinking of building the Challenger inukshuk. A check showed that there was already a nice base made from remnants of an ancient coral reef. Plenty of rocks are to be found nearby. We’ll be back in a few days to do the actual construction.

Leroy Chiao, Joseph Atchealak, and Jarloo Kiguktak standing on the border of Inuit Owned Land inside Haughton Crater

We then headed off toward Haughton Crater. We quickly passed through an alien landscape that was created when the remnants of a coral reef were eroded by the action of water and ice. The rocks are from the Silurian – hundreds of millions of years old. You could film a science fiction movie here; indeed, I was reminded of some of the landscapes I saw as Kid on “Lost in Space”.

Pascal Lee and his dog Ping Pong at a stop along our traverse — Keith Cowing

We soon stopped at the Inukshuk for Kalpana Chawla, which overlooks Trinity Lake on one side and the vast expanse of Haughton Crater on the other. Leroy and I hiked up the several hundred feet of rough terrain to the small summit. The inukshuk had lost a few key stones over the past few seasons, so we replaced them.

Inukshuk Kalpana Chawla — Keith Cowing

Next stop was a large ejecta block that had been thrown out from the original impact itself. Upon close examination you can see that it was excavated from deep underground. The rock structure contains a cross section of fossil bearing rock that was already incredibly ancient when the impact event occurred.

As we headed further into the crater we crossed a variety of terrains. Muddy flat streams, dry dusty plains, vast expanses strewn with rocks several feet in diameter – and often larger. When riding an ATV, the trick is to keep a steady speed, shift gears appropriately and stay in formation.

Ancient coral reef — Keith Cowing

Soon, we entered regions that I had never seen before. The valleys were caused by the action of ice scraping across the landscape. The valleys that were left behind were stunning and some were just plain magnificent. With the exception of a few artic willows and poppies, the landscape seemed to be devoid of all life. This just served to enhance the otherworldly aspects of the places we visited.

We passed through Shoemaker Valley and ended up atop a ridge where you could see quite a distance across the crater floor. Some regions were grayish-white. This was a breccias deposit – shattered, pulverized rocks from the impact event. When you pass over such a breccias field you can find pieces of granite that were excavated from deep within this island – to a depth of up to a mile – by the impact event.

There are also small whitish gray stones with fan-like radiating patterns. These are called “shatter cones” and capture the shock of the impact event itself as it traveled through and shocked the underlying rock layers.

After a snack of smoked oysters and anchovies (always a highlight of a traverse) we began the trek home.

Keith Cowing (front) and Matt Reyes (behind) on ATVs during a traverse. — Keith Cowing

I am now sitting here writing this entry just before 11:00 pm. I am sitting outside facing due west. The sun is to my right, heading north – and low – on the horizon. My face is tight and slightly tingly – the combined after effect of incredibly strong sunlight (lots of UV), wind, dryness, and cold – all accentuated by 4 hours of driving around on ATVs amidst clouds of fine, swirling dust.

Inside the mess tent some folks are watching a movie (“Red Planet”). The K10 rover team from NASA Ames just finished an evening meeting after a productive day. Meanwhile, a bunch of geologists are in the Hub sifting and analyzing samples they brought in from the field. Out in the greenhouse, as the twin wind generators whoosh away, systems are being upgraded and checked for another season of autonomous operation.

Elsewhere, the communications folks are checking the performance of various systems, Jesse the mechanic is making sure the ATV fleet is working, and Base Camp management is planning the next days’ events.

Above my head, on a support wire which helps hold up a radio antenna, a small strand of Lung Ta prayer flags from Tibet flutter silently in the evening breeze.

For me, Leroy and Matt, we have our first live webcast with a dozen Challenger Learning Centers tomorrow. We did several full up tests today to make certain that all the components of a life webcast from the arctic will go as planned tomorrow.

As I sit here in this stark yet stunning place, I decided to inject another world by playing a nature soundtrack on my iPhone. As such I am sitting here surrounded by a forest full of life – virtual life, that is.

I have to wonder what the first people to visit Mars will do on a similar late night session of reflection. Will they wander into greenhouses and smell the plants, play nature sounds, and watch movies from back home? Or will new ways of relaxing emerge – ones that are wholly human – yet also, part Martian?

About Devon Island, The Haughton-Mars Project, and the Mars Institute

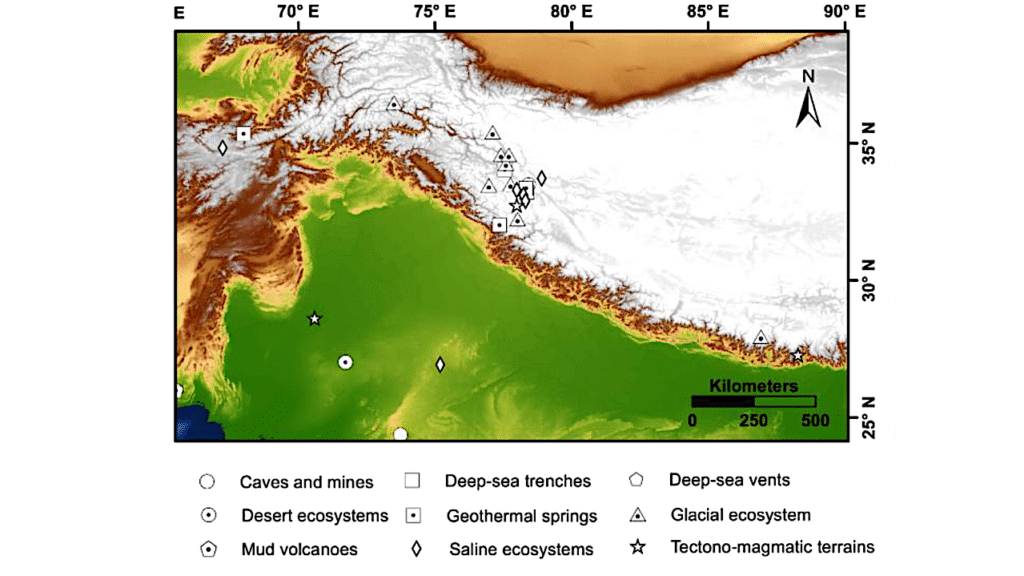

The Haughton-Mars Project (HMP) is an international interdisciplinary field research project centered on the scientific study of the Haughton impact structure and surrounding terrain, Devon Island, high arctic, viewed as a terrestrial analog for Mars. The rocky polar desert setting, geologic features and biological attributes of the site offer unique insights into the possible evolution of Mars – in particular the history of water and of past climates on Mars, the effects of impacts on Earth and on other planets, and the possibilities and limits of life in extreme environments. In parallel with its science program, the HMP supports an exploration program aimed at developing new technologies, strategies, humans factors experience, and field-based operational know-how key to planning the future exploration of the Moon, Mars and other planets by robots and humans. The HMP managed jointly by the Mars Institute and by the SETI Institute.

Astrobiology,