Kepler-62 Has Two Water Worlds Circling in its Habitable Zone

In our solar system, only one planet is blessed with an ocean: Earth. Our home world is a rare, blue jewel compared to the deserts of Mercury, Venus and Mars. But what if our Sun had not one but two habitable ocean worlds?

Astronomers have found such a planetary system orbiting the star Kepler-62. This five-planet system has two worlds in the habitable zone — the distance from their star at which they receive enough light and warmth for liquid water to theoretically exist on their surfaces. Modeling by researchers at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) suggests that both planets are water worlds, their surfaces completely covered by a global ocean with no land in sight.

“These planets are unlike anything in our solar system. They have endless oceans,” said lead author Lisa Kaltenegger of the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy and the CfA. “There may be life there, but could it be technology-based like ours? Life on these worlds would be under water with no easy access to metals, to electricity, or fire for metallurgy. Nonetheless, these worlds will still be beautiful blue planets circling an orange star — and maybe life’s inventiveness to get to a technology stage will surprise us.”

Kepler-62 is a type K star slightly smaller and cooler than our Sun. The two water worlds, designated Kepler-62e and -62f, orbit the star every 122 and 267 days, respectively.

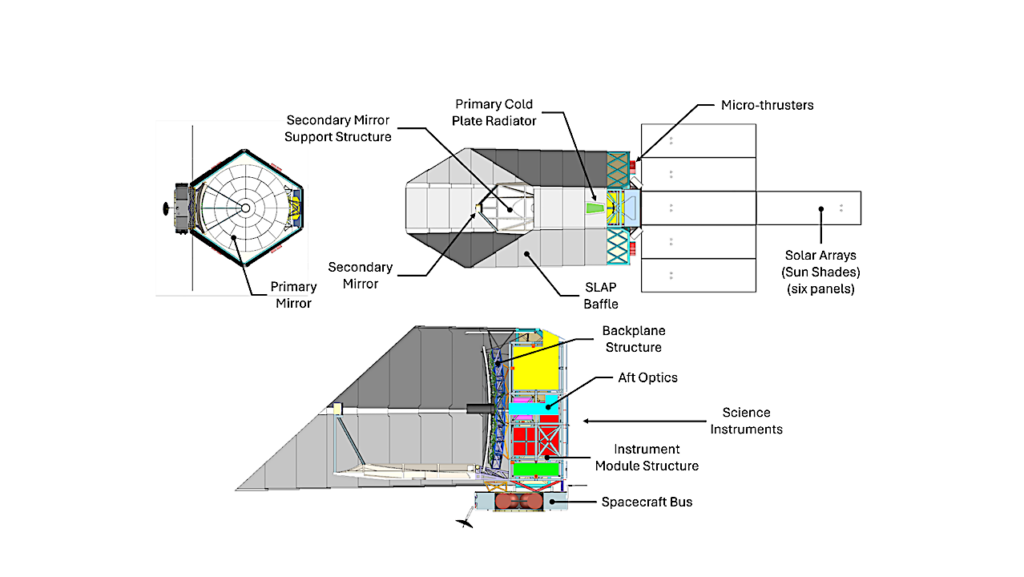

They were found by NASA’s Kepler spacecraft, which detects planets that transit or cross the face of their host star. Measuring a transit tells astronomers the size of the planet relative to its star.

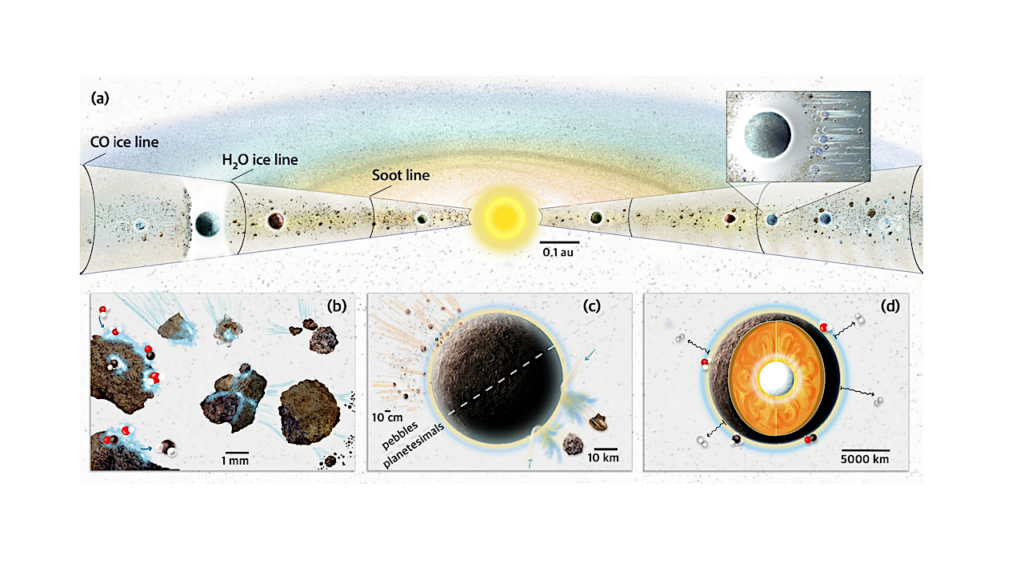

Kepler-62e is 60 percent larger than the Earth while Kepler-62f is about 40 percent larger, making both of them “super-Earths.” They are too small for their masses to be measured, but astronomers expect them to be composed of rock and water, without a significant gaseous envelope.

As the warmer of the two worlds, Kepler-62e would have a bit more clouds than Earth according to computer models. More distant Kepler-62f would need the greenhouse effect from plenty of carbon dioxide to warm it enough to host an ocean. Otherwise, it might become an ice-covered snowball.

“Kepler-62e probably has a very cloudy sky and is warm and humid all the way to the polar regions. Kepler-62f would be cooler, but still potentially life-friendly,” said Harvard astronomer and co-author Dimitar Sasselov.

“The good news is — the two would exhibit distinctly different colors and make our search for signatures of life easier on such planets in the near future,” he added.

The discovery raises the intriguing possibility that some star in our galaxy might be circled by two Earth-like worlds — planets with oceans and continents, where technologically advanced life could develop.

“Imagine looking through a telescope to see another world with life just a few million miles from your own. Or, having the capability to travel between them on a regular basis. I can’t think of a more powerful motivation to become a space-faring society,” said Sasselov.

Kaltenegger and Sasselov’s research has been accepted for publication in The Astrophysical Journal.

Contacts:

David Aguilar

+1 617-495-7462

[email protected]

Christine Pulliam

+1 617-495-7463

[email protected]

Headquartered in Cambridge, Mass., the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA) is a joint collaboration between the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory and the Harvard College Observatory. CfA scientists, organized into six research divisions, study the origin, evolution and ultimate fate of the universe.