Cheops Discovers Late Bloomer Planet From Another Era

Many Vile Earthlings Munch Jam Sandwiches Under Newspapers and My Very Educated Mother Just Served Us Nachos. What sounds like gibberish half-sentences are memory aids taught to children to help remember the order of the planets in our Solar System: Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune.

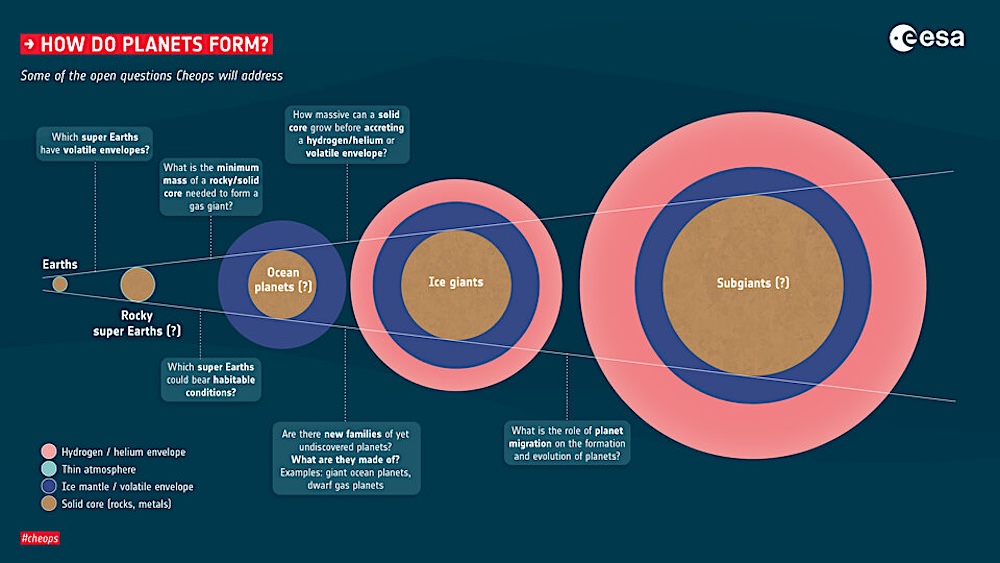

The eight familiar planets can be sorted into two different types: rocky and gaseous. The inner planets that are closest to the Sun – Mercury to Mars – are rocky, and the outer planets – Jupiter to Neptune – are gaseous.

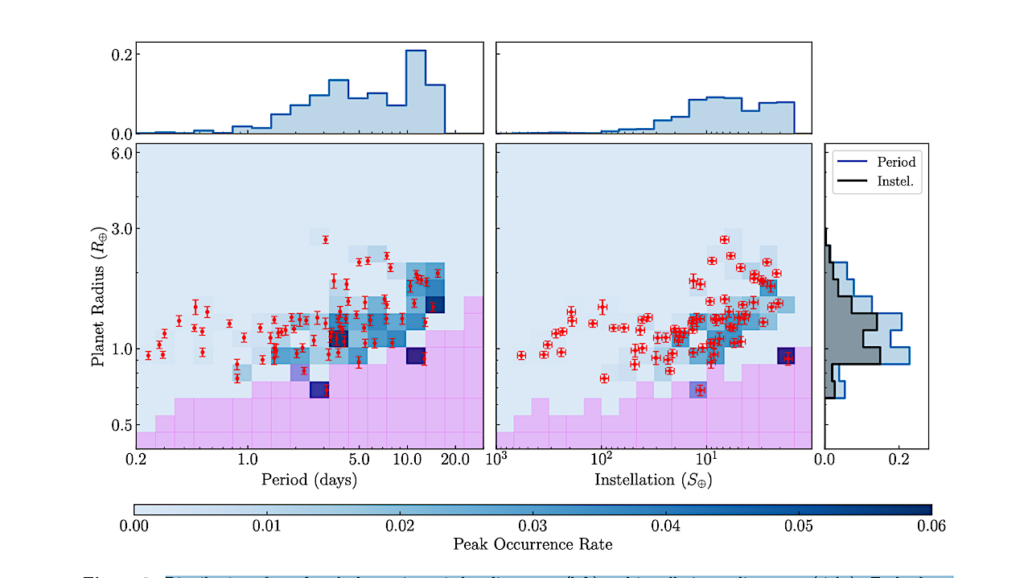

This general pattern, that planetary systems form with rocky planets closer to their star, followed by gaseous planets as the outer bodies, has been commonly observed across the Universe. It is what our current planet formation theories predict and what observations have widely confirmed to be true.

That was until scientists took a closer look at the planetary system around a star called LHS 1903 with ESA’s CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (Cheops). What they have just discovered might flip our understanding of how planets form upside down.

The four planets of LHS 1903 – LHS 1903 b, c, d, and e — ESA

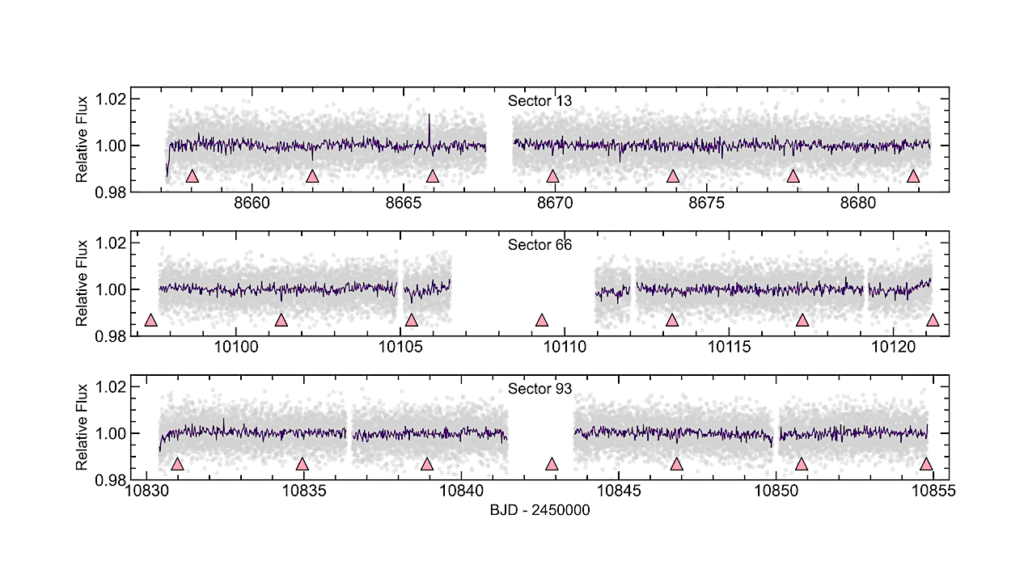

LHS 1903 is a small red M-dwarf star that is cooler and shines less brightly than our Sun. Thomas Wilson from the University of Warwick in the UK and his international team combined the efforts of various telescopes in space and on Earth to classify three planets that they had spotted orbiting LHS 1903. They were able to conclude that the innermost planet seemed to be rocky, and the two that followed it gaseous.

So far, so normal. It wasn’t until Thomas and his colleagues were analysing observations made by ESA’s Cheops, that they discovered something strange: the data showed a small fourth planet, furthest from LHS 1903. And upon closer inspection, the scientists were surprised to discover that this planet seems to be rocky!

“That makes this an inside-out system, with a planet order of rocky-gaseous-gaseous-and then rocky again. Rocky planets don’t usually form so far away from their home star,” says Thomas.

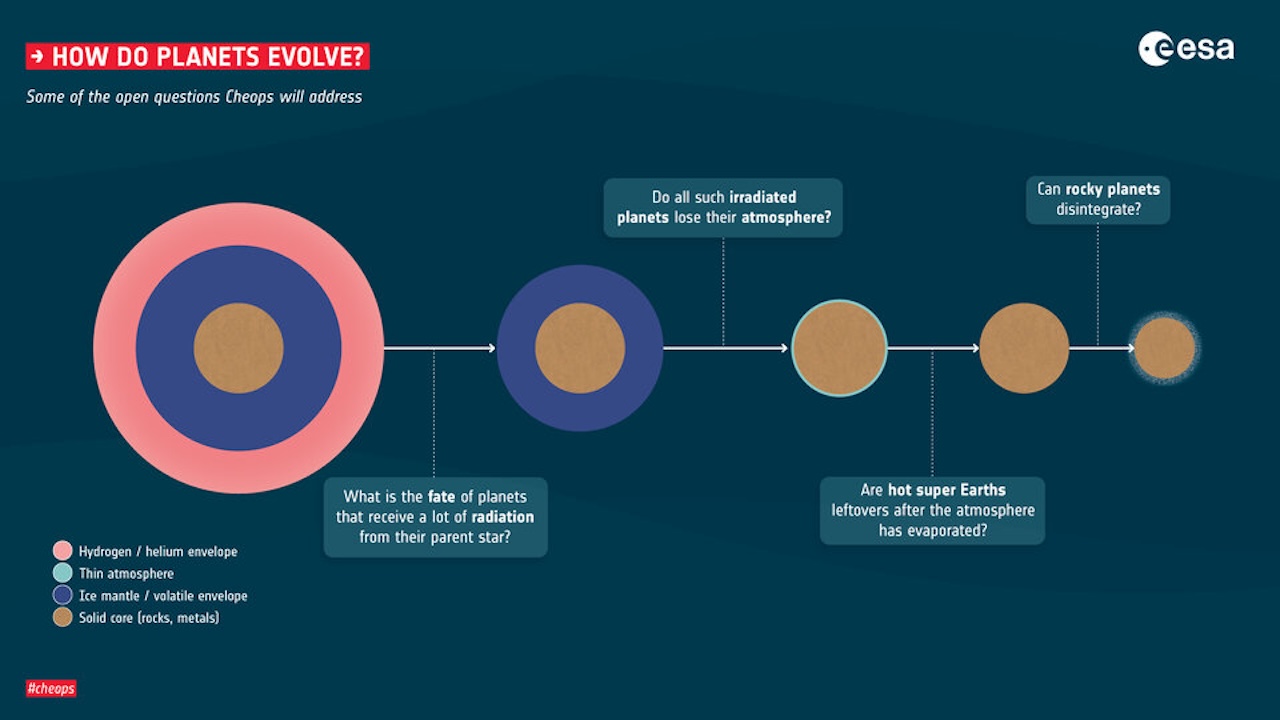

Current planet formation theories predict that the inner planets in a system are small and rocky, because close to the star the radiation is so powerful that it sweeps away most of the gas around the planets’ rocky core. Further away from the star, in the outer part of a planetary system, the conditions are cool enough for a thick atmosphere to gather into a gaseous planet.

ESA’s Cheops project scientist Maximilian Günther is enthusiastic: “Much about how planets form and evolve is still a mystery. Finding clues like this one for solving this puzzle is precisely what Cheops set out to do.”

Born to be weird?

Scientists are not quick to say that an established theory needs to be reconsidered, based on a single contradictory observation. So, Thomas and his colleagues set out to explore various explanations for why this strange rocky planet breaks the familiar pattern.

Cheops open questions: How do planets evolve?— ESA

Was the planet, for example, at some point in its past hit by a giant asteroid, comet, or another big object, that blew away its atmosphere? Or had the planets around LHS 1903 swapped places at some point during their evolution? After testing these scenarios through simulations and calculations of the planets’ orbital times, the team of scientists ruled them out.

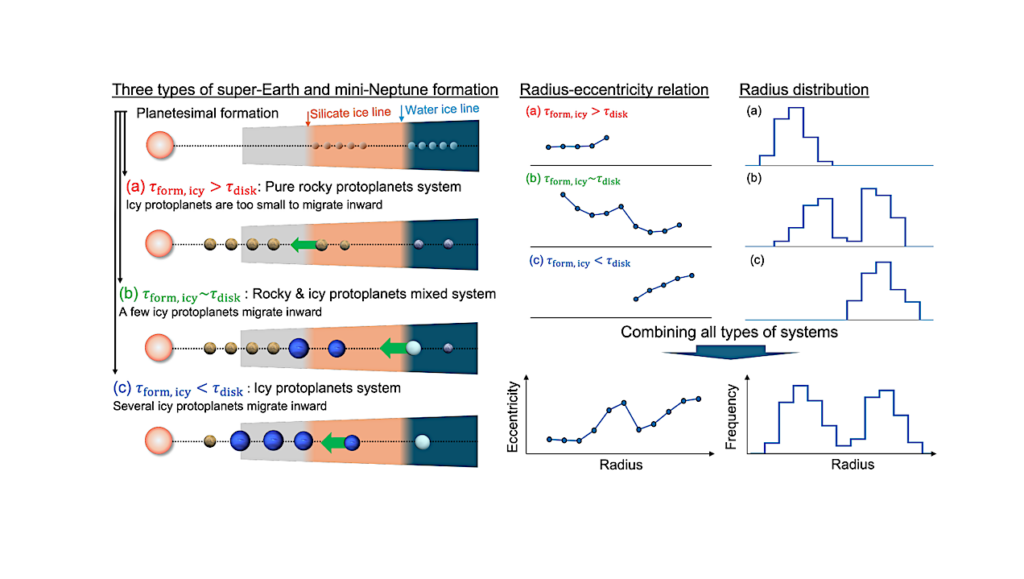

Instead, their investigation led them to a more intriguing explanation: the planets may have formed one after the other, instead of at the same time. According to our current understanding, planets form from discs of gas and dust (protoplanetary discs) by clumping into planetary embryos at roughly the same time. These clumps then evolve into planets of different sizes and compositions over millions of years.

In contrast, here Thomas and his team discovered a planetary system where the star might have given birth to its four planets one after the other, instead of bearing quadruplets at once. This idea – known as inside-out planet formation – was proposed by scientists as a theory about a decade ago, but until now, never has the evidence been so strong.

A late bloomer defying expectations

This conclusion comes with an additional catch: Much like how our younger siblings are growing up in a world that is different from the one of our childhoods, this small rocky planet seems to have evolved and formed in a very different environment than its older sibling-planets.

“By the time this outer planet formed, the system may have already run out of gas, which is considered vital for planet formation. Yet here is a small, rocky world, defying expectations. It seems that we have found first evidence for a planet which formed in what we call a gas-depleted environment”, says Thomas.

The small rocky world is either an odd outlier, or the first evidence for a trend we hadn’t known about yet. Either way, its discovery begs for an explanation that lies beyond our usual planet formation theories.

Our Solar System as a one-size-fits-all

“Historically, our planet formation theories are based on what we see and know about our Solar System,” Isabel Rebollido who is currently a Research Fellow at ESA points out. “As we are seeing more and more different exoplanet systems, we are starting to revisit these theories.”

As our instruments improve, we continue to discover more and more ‘weird’ planetary systems in the vastness of space. They force us to question our understanding and make us reconsider established theories of planet formation. Ultimately, these discoveries are helping us learn about how our Solar System fits into the big family of diverse planetary systems. They make us wonder how special the order of the planets is that we teach our children, and if maybe it is our home Solar System that is the weird one after all.

‘Gas-depleted planet formation occurred in the four-planet system around theLHS 1903 b red dwarf LHS 1903‘ by T. Wilson et al. is published in Science on 12 February 2026. DOI:10.1126/science.adl2348

Astrobiology,