Raman Spectroscopy Of Salt Deposits From The Simulated Subsurface Ocean Of Enceladus

Saturn’s ice-covered moon Enceladus may host a subsurface ocean with biologically relevant chemistry.

Plumes released from this ocean preserve information on its chemical state, and previous analyses suggest weakly to strongly alkaline pH (approximately pH 8–12). Constraining the pH requires identification of pH-sensitive minerals in plume deposits. Several analytical techniques could provide such mineralogical information, but few are practical for deployment on planetary missions.

Raman spectrometers, which have recently advanced for in situ exploration and have been incorporated into flight instruments, offer a feasible approach for mineral identification on icy moons. However, their applicability to pH estimation from plume-derived minerals has not been investigated.

In this study, we evaluate whether Raman measurements of plume particles deposited on the surface of Enceladus can be used to distinguish between weakly and strongly alkaline subsurface ocean models. Fluids with pH values of 9 and 11 were frozen under vacuum conditions analogous to those on Enceladus. The resulting salt deposits were then analyzed using a flight-like Raman spectrometer.

The Raman spectra show pH-dependent carbonate precipitation: NaHCO3 and Na2CO3 peaks were detected at pH 9, whereas only Na2CO3 peaks were detected at pH 11. These findings demonstrate that Raman spectroscopy can distinguish pH-dependent carbonate phases. This capability allows us to constrain whether the pH of the subsurface ocean is weakly alkaline or strongly alkaline, which is a key parameter for assessing its chemical evolution and potential habitability.

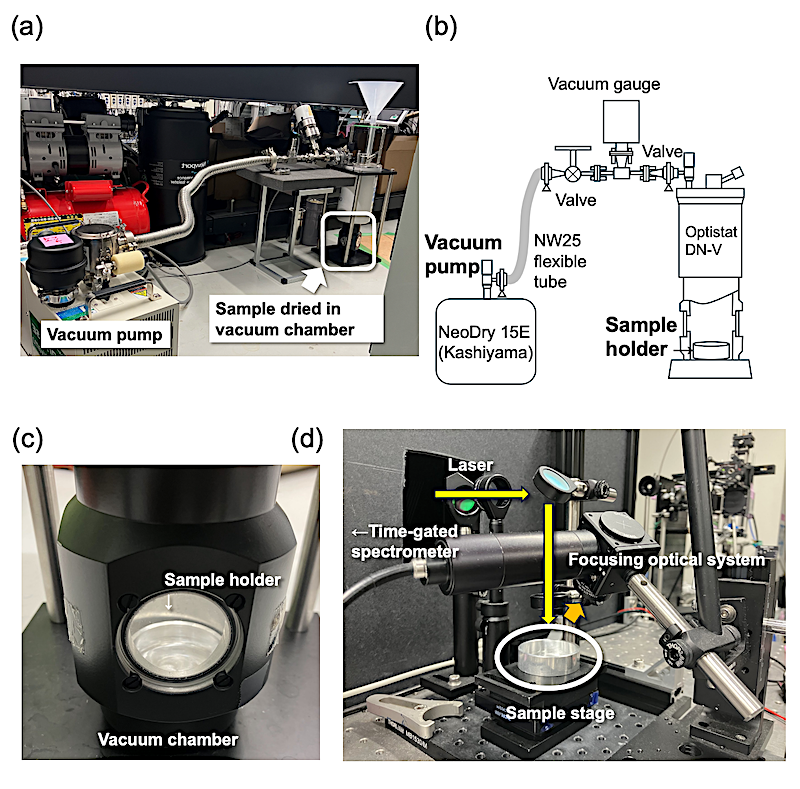

Cooling experimental apparatus. (a) Photograph and (b) schematic diagram of the dry freezing system. (c) The sample chamber with a sample (i.e., a frozen solution) in the chamber. Above this is a cooler filled with liquid nitrogen. (d) Photograph of the Raman spectrometer. — astro-ph.EP

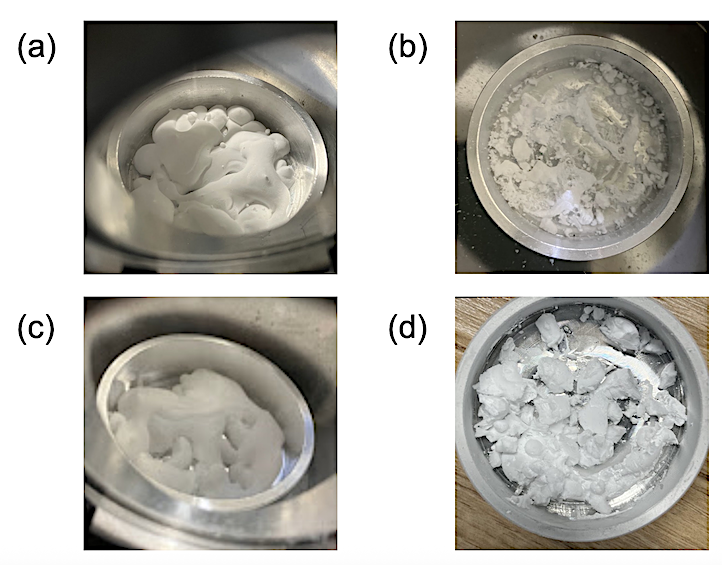

Photographs of the samples at (a) pH = 9 immediately after starting vacuum pumping and (b) pH = 9 after 18 h of vacuum pumping, (c) pH = 11 immediately after starting vacuum pumping, and (d) pH = 11 after 18 h of vacuum pumping. The sample holder is 5 cm in diameter. — astro-ph.EP

Jun Takeshita, Yuichiro Cho, Haruhisa Tabata, Yoshio Takahashi, Daigo Shoji, Seiji Sugita

Subjects: Earth and Planetary Astrophysics (astro-ph.EP)

Cite as: arXiv:2512.19183 [astro-ph.EP] (or arXiv:2512.19183v1 [astro-ph.EP] for this version)

https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2512.19183

Focus to learn more

Submission history

From: Jun Takeshita

[v1] Mon, 22 Dec 2025 09:17:45 UTC (6,255 KB)

https://arxiv.org/abs/2512.19183

Astrobiology, Astrogeology,