How Life Appeared: Rise Of The Nanomachines

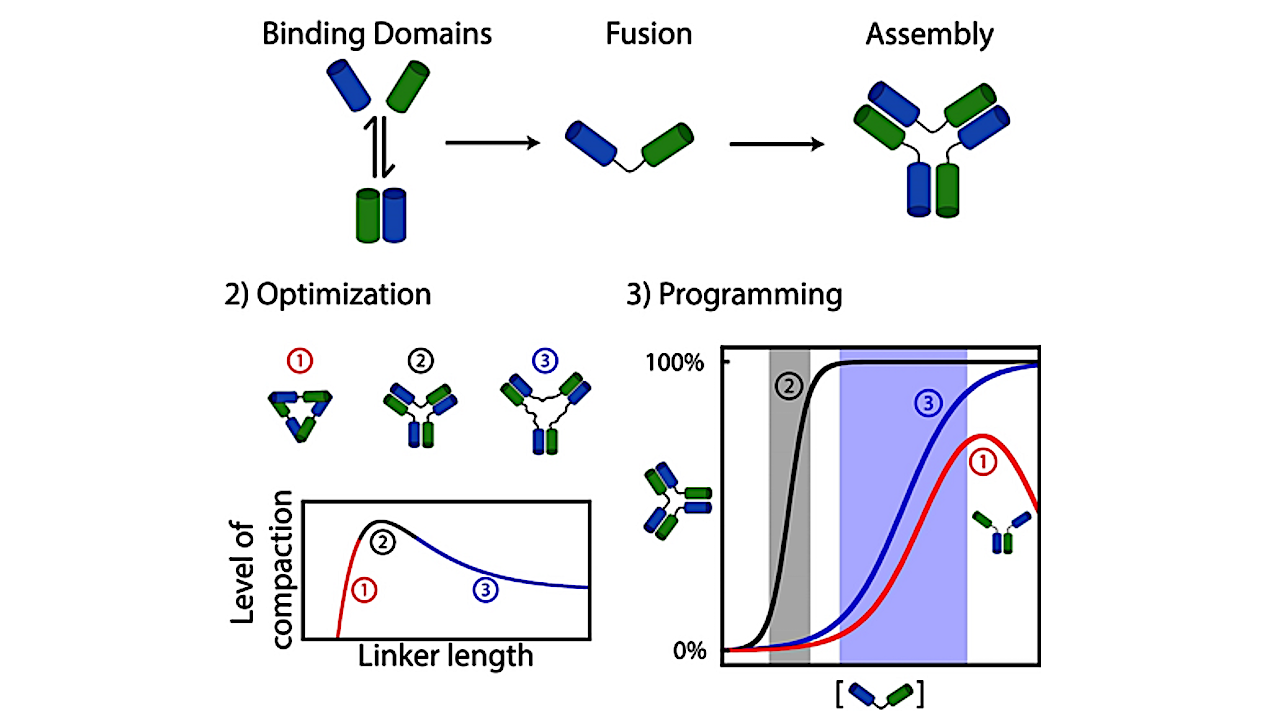

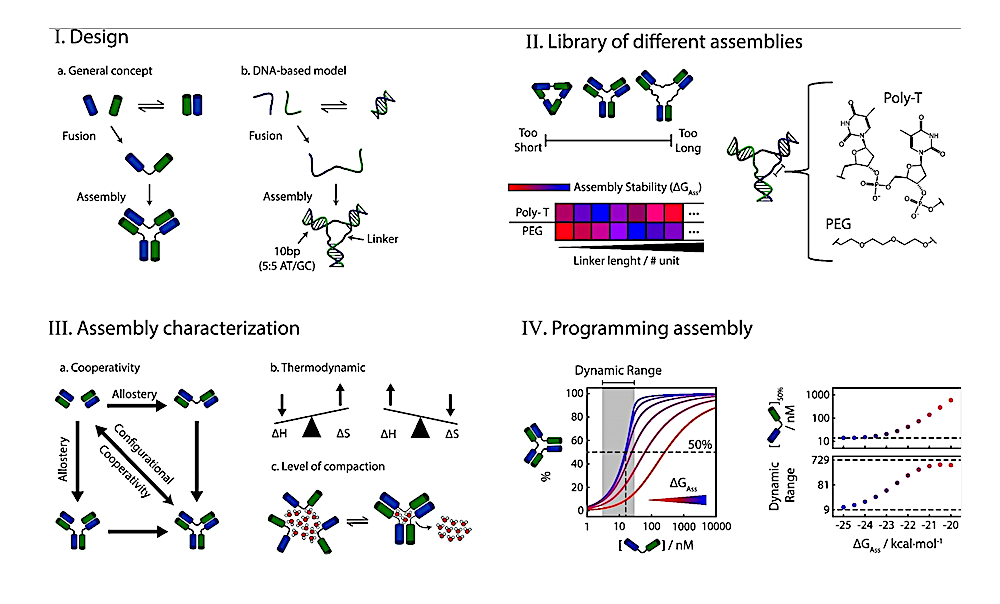

Molecular assembly can be designed by fusing binding domains. A precise optimization of the level of compaction of the assembly using linker of different lengths or compositions can provide a simple strategy to program their assembly properties (e.g., midpoint, dynamic range, and inhibition). The thermodynamic and mechanistic principles demonstrated herein also shine light behind the evolution of biological molecular assembly.

By attaching molecules together, scientists at Université de Montréal think they’ve found how molecular systems at the origin of life evolved to create complex self-regulating functions.

Published in the European journal Angewandte Chemie, their findings promise to provide chemists and nanotechnologists with a simple strategy to create the next generation of dynamic nanosystems.

Life on Earth is sustained by millions of different tiny nanostructures or nanomachines that have evolved over millions of years, explained Alexis Vallée-Bélisle, an UdeM professor and principal investigator of the study.

These structures, often smaller than 10,000 times the diameter of a human hair, are typically composed of proteins or nucleic acids. While some are made from a single component or part (often linear polymers that fold into a specific structure), most of them are made using several components that spontaneously assemble into large and dynamic assemblies.

Responding to stimuli

“These molecular assemblies are highly dynamic and activate or deactivate precisely in response to various stimuli such as a variation in temperature, oxygen, or nutrients,” said Vallée-Bélisle.

“Similarly to cars that require sequential ignition, brake release, gear change and gas input to move forward, molecular systems require the sequential activation or deactivation of various nanomachines to perform any specific tasks ranging from moving, breathing to thinking.”

The researchers raised a fundamental question: how have dynamic molecular assemblies been created, programmed and fine-tuned to support life?

What they found is that many biological assemblies were likely formed by randomly attaching interacting molecules (e.g., proteins or nucleic acids such as DNA or RNA) with linkers acting like a “connector” between each part.

“As these biomolecular assemblies play a crucial role in enabling living organisms to respond to their environment, we have hypothesized that the nature of the connectivity between the attached components may also contribute to the evolution of their dynamic responses,” said Vallée-Bélisle, holder of the Canada Research Chair in Bioengineering and Bio-Nanotechnology.

Exploring the impact of connectivity

To explore this question, Dominic Lauzon, a doctoral student at the time of the study, decided to synthesize and attach dozens of DNA interacting molecules together to explore the impact of connectivity on the dynamic of assembly.

“The programmable, easy-to-use, chemistry of nucleic acids such as DNA makes it a convenient molecule to study fundamental questions related to the evolution of biomolecules” said Lauzon, the first author of the study. “Furthermore, nucleic acids are also thought to be the molecule at the origin of life on earth”.

Lauzon and Vallée-Bélisle discovered that a simple variation in the “linker” length between the interacting molecules leads to significant variations in their assembly dynamics. For instance, certain assemblies exhibited high sensitivity to variation in stimuli, while others lacked such sensitivity, or even required much larger changes in stimuli to promote assembly. More surprisingly, some linkers even created new complex regulatory functions such as self-inhibition properties, where the addition of a stimulus would both promote its assembly and its disassembly. All these different responsive behaviours are also often observed in natural “living” nanomachines.

Using experiments and mathematical equations, the researchers were also able to explain why such a simple variation of linker length was so efficient at modifying the dynamics of molecular assembly. “The linkers creating the most stable assemblies were the ones also creating the most sensitive activation mechanisms, while the linkers creating the less stable assemblies created the less sensitive activation mechanisms, even to the point of introducing self-inhibition,” explained Lauzon.

Programming molecular assemblies by connecting interacting domains. I. Design. Left. A trimeric assembly can be engineered through the assembly of three components built by linking two interacting domains (blue and green) together using a linker (black). Right. Our model system consists of a DNA interacting domains (10 nucleotides) connected via a linker that specifically form a trimeric assembly. Of note, binding domains were specifically designed to favour trimeric assembly over monomers or dimers (see DNA sequences in Supporting Information). II. Library of different assemblies. We prepared a library of trimeric assemblies with different stability (ΔGAss) by varying the linker connection (e.g., poly-T, PEG, length, …), with shorter linkers expected to prevent some interaction due to steric hindrance and longer linkers expected to compromise assembly due to higher entropic cost. III. Assembly characterization. Each assembly are thoroughly characterized to identify the main parameter that favours their assembly: cooperativity, thermodynamic contributions, or level of compaction. IV. Programming assembly. Numerical simulations of a trimeric assembly reveal the programming potential of stabilizing or destabilizing the assembly. More stable assemblies produce system assembling at lower concentration with narrow dynamic ranges while less stable assemblies produce system assembling at higher concentration with extended dynamic ranges. See the Supporting Information for the details regarding the simulation.

Sensing is crucial

The ability to sense molecular signals precisely is crucial for biological assemblies but also in the development of nanotechnology that depends on the detection and integration of molecular information.

The researchers therefore believe that their discovery may also provide the fundamental framework to create more programmable nanomachines or nanosystems with optimally regulated activities – for instance, by simply attaching interacting molecules with varying linkers. Such molecular assemblies are already finding applications in biosensing or drug delivery.

In addition to providing a simple design strategy to create the next generation of self-regulated nanosystems, the scientists’ discoveries also shed light on how natural biomolecular assemblies may have acquired their optimal dynamics.

“One well-known molecular evolution strategy of living organisms is gene fusion, where the DNA coding for two interacting protein domains are randomly fused,” said Vallée-Bélisle. “Our findings also provide the fundamental understanding required to comprehend how a simple variation in the linker length between the fused proteins may have efficiently created biological assemblies displaying a variety of dynamics, some better suited than others to provide an advantage to living organisms.”

About this study

“Design and thermodynamic principles to program the cooperativity of molecular assemblies,”(open access) by Dominic Lauzon and Alexis Vallée-Bélisle, was published Nov. 17, 2023 in Angewandte Chemie. Funding was provided by the National Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada and Les Fond de recherche du Québec – Nature et technologies.

Astrobiology, Nanotechnology,