Earth Life Biodiversity: Vast DNA Tree Of life For Flowering Plants Revealed

The most up-to-date understanding of the flowering plant tree of life is presented in a new study published today in the journal Nature by an international team of 279 scientists, including three University of Michigan biologists.

Using 1.8 billion letters of genetic code from more than 9,500 species covering almost 8,000 known flowering plant genera (ca. 60%), this achievement sheds new light on the evolutionary history of flowering plants and their rise to ecological dominance on Earth.

Led by scientists at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, the research team believes the data will aid future attempts to identify new species, refine plant classification, uncover new medicinal compounds, and conserve plants in the face of climate change and biodiversity loss.

The major milestone for plant science, involving 138 organizations internationally, was built on 15 times more data than any comparable studies of the flowering plant tree of life. Among the species sequenced for this study, more than 800 have never had their DNA sequenced before.

The sheer amount of data unlocked by this research, which would take a single computer 18 years to process, is a huge stride toward building a tree of life for all 330,000 known species of flowering plants—a massive undertaking by Kew’s Tree of Life Initiative.

“Analyzing this unprecedented amount of data to decode the information hidden in millions of DNA sequences was a huge challenge. But it also offered the unique opportunity to reevaluate and extend our knowledge of the plant tree of life, opening a new window to explore the complexity of plant evolution,” said Alexandre Zuntini, a research fellow at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Tom Carruthers, postdoctoral researcher in the lab of U-M evolutionary biologist Stephen Smith, is co-lead author of the study with Zuntini, who he previously worked with at Kew. U-M plant systematist Richard Rabeler is a co-author.

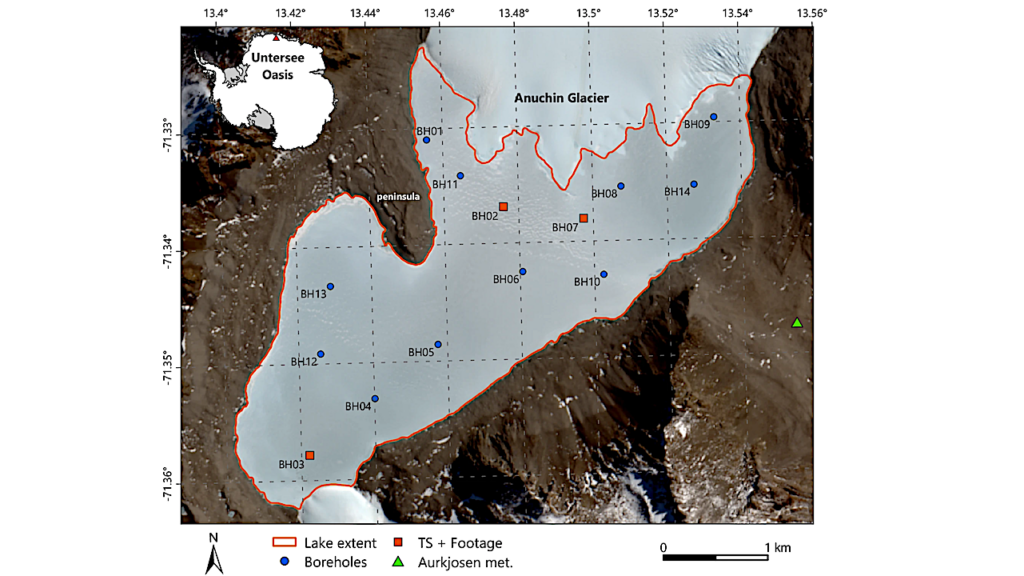

All 64 orders, all 416 families and 58% (7,923) of genera are represented. The young tree is illustrated here (maximum constraint at the root node of 154 Ma), with branch colours representing net diversification rates. Black dots at nodes indicate the phylogenetic placement of fossil calibrations based on the updated AngioCal fossil calibration dataset. Note that calibrated nodes can be older than the age of the corresponding fossils owing to the use of minimum age constraints. Arcs around the tree indicate the main clades of angiosperms as circumscribed in this paper. ANA grade refers to the three consecutively diverging orders Amborellales, Nymphaeales and Austrobaileyales. Plant portraits illustrating key orders were sourced from Curtis’s Botanical Magazine (Biodiversity Heritage Library). These portraits, by S. Edwards, W. H. Fitch, W. J. Hooker, J. McNab and M. Smith, were first published between 1804 and 1916 (for a key to illustrations see Supplementary Table 2). A high-resolution version of this figure can be downloaded from https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.10778206 (ref. 55).

“Flowering plants feed, clothe and greet us whenever we walk into the woods. The construction of a flowering plant tree of life has been a significant challenge and goal for the field of evolutionary biology for more than a century,” said Smith, co-author of the study and professor in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology. “This project moves us closer to that goal by providing a massive dataset for most of the genera of flowering plants and offering one strategy to complete this goal.”

Smith had two roles on the project. First, members of his lab—including former U-M graduate student Drew Larson—traveled to Kew to help sequence members of a large and diverse plant group called Ericales, which includes blueberries, tea, ebony, azaleas, rhododendrons and Brazil nuts.

Second, Smith supervised the analyses and construction of the project dataset along with William Baker and Felix Forest of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, and Wolf Eisenhardt of Aarhus University.

“One of the biggest challenges faced by the team was the unexpected complexity underlying many of the gene regions, where different genes tell different evolutionary histories. Procedures had to be developed to examine these patterns on a scale that hadn’t been done before,” said Smith, who is also director of the Program in Biology and an associate curator in biodiversity informatics at the U-M Herbarium.

As co-leader of the study, Carruthers’ main responsibilities included scaling the evolutionary tree to time using 200 fossils, analyzing the different evolutionary histories of the genes underlying the overall evolutionary tree, and estimating rates of diversification in different flowering plant lineages at different times.

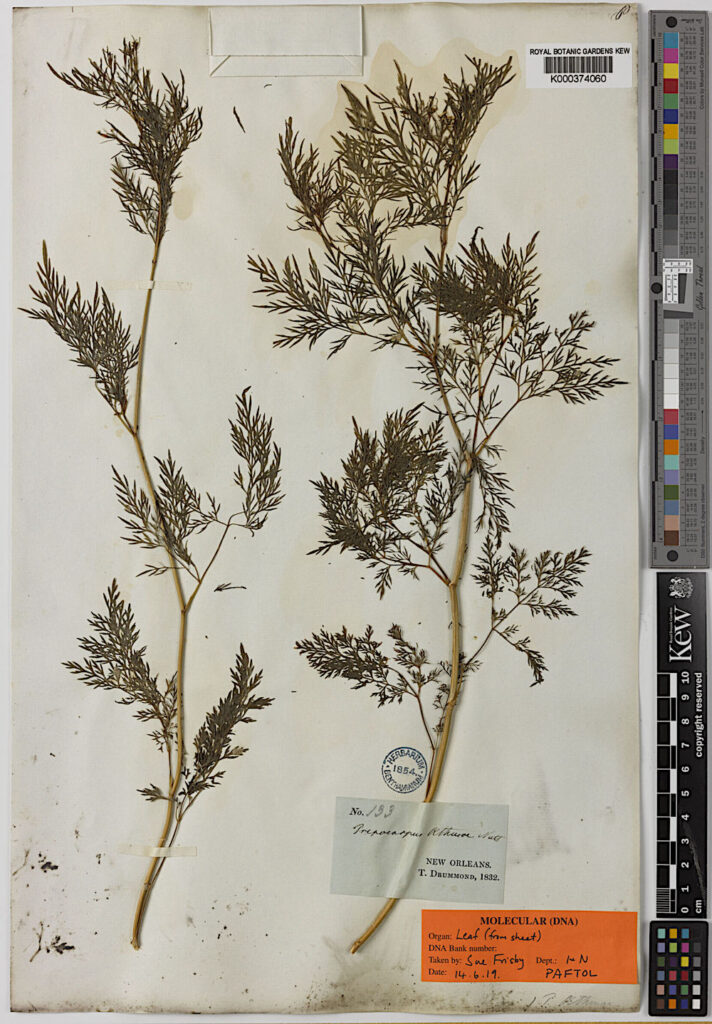

Hebarium speciment from 1832 – Trepocarpus aethusae – RBG Kew

“Constructing such a large tree of life for flowering plants, based on so many genes, sheds light on the evolutionary history of this special group, helping us to understand how they came to be such an integral and dominant part of the world,” Carruthers said. “The evolutionary relationships that are presented—and the data underlying them—will provide an important foundation for a lot of future studies.”

The flowering plant tree of life, much like our own family tree, enables us to understand how different species are related to each other. The tree of life is uncovered by comparing DNA sequences between different species to identify changes (mutations) that accumulate over time like a molecular fossil record.

Our understanding of the tree of life is improving rapidly in tandem with advances in DNA sequencing technology. For this study, new genomic techniques were developed to magnetically capture hundreds of genes and hundreds of thousands of letters of genetic code from every sample, orders of magnitude more than earlier methods.

A key advantage of the team’s approach is that it enables a wide diversity of plant material, old and new, to be sequenced, even when the DNA is badly damaged. The vast treasure troves of dried plant material in the world’s herbarium collections, which comprise nearly 400 million scientific specimens of plants, can now be studied genetically.

“In many ways this novel approach has allowed us to collaborate with the botanists of the past by tapping into the wealth of data locked up in historic herbarium specimens, some of which were collected as far back as the early 19th century,” said Baker, senior research leader for Kew’s Tree of Life Initiative.

“Our illustrious predecessors, such as Charles Darwin or Joseph Hooker, could not have anticipated how important these specimens would be in genomic research today. DNA was not even discovered in their lifetimes. Our work shows just how important these incredible botanical museums are to groundbreaking studies of life on Earth. Who knows what other undiscovered science opportunities lie within them?”

Across all 9,506 species sequenced, more than 3,400 came from material sourced from 163 herbaria in 48 countries.

“Sampling herbarium specimens for the study of plant relationships makes broad sampling from diverse areas of the world much more feasible than if one had to travel to get fresh material from the field,” said U-M’s Rabeler, a research scientist emeritus and former collection manager at the U-M Herbarium.

For the tree of life project, Rabeler helped verify the identity of herbarium specimens selected for sampling and analyzed the resulting data.

Flowering plants alone account for about 90% of all known plant life on land and are found virtually everywhere on the planet—from the steamiest tropics to the rocky outcrops of the Antarctic Peninsula. And yet, our understanding of how these plants came to dominate the scene soon after their origin has baffled scientists for generations, including Darwin.

Flowering plants originated more than 140 million years ago after which they rapidly overtook other vascular plants including their closest living relatives—the gymnosperms (nonflowering plants that have naked seeds, such as cycads, conifers and ginkgo).

Darwin was mystified by the seemingly sudden appearance of such diversity in the fossil record. In an 1879 letter to Hooker, his close confidant and director of the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, he wrote: “The rapid development as far as we can judge of all the higher plants within recent geological times is an abominable mystery.”

Using 200 fossils, the authors scaled their tree of life to time, revealing how flowering plants evolved across geological time. They found that early flowering plants did indeed explode in diversity, giving rise to more than 80% of the major lineages that exist today shortly after their origin.

However, this trend then declined to a steadier rate for the next 100 million years until another surge in diversification about 40 million years ago, coinciding with a global decline in temperatures. These new insights would have fascinated Darwin and will surely help today’s scientists grappling with the challenges of understanding how and why species diversify.

Assembling a tree of life this extensive would have been impossible without Kew’s scientists collaborating with many partners across the globe. In total, 279 authors were involved in the research, representing many different nationalities from 138 organizations in 27 countries.

“The plant community has a long history of collaborating and coordinating molecular sequencing to generate a more comprehensive and robust plant tree of life. The effort that led to this paper continues in that tradition but scales up quite significantly,” said U-M’s Smith.

The flowering plant tree of life has enormous potential in biodiversity research. This is because, just as one can predict the properties of an element based on its position in the periodic table, the location of a species in the tree of life allows us to predict its properties. The new data will thus be invaluable for enhancing many areas of science and beyond.

To enable this, the tree and all of the data that underpin it have been made openly and freely accessible to both the public and scientific community, including through the Kew Tree of Life Explorer.

Open access will help scientists to make the best use of the data, such as combining it with artificial intelligence to predict which plant species may include molecules with medicinal potential.

Similarly, the tree of life can be used to better understand and predict how pests and diseases are going to affect plants in the future. Ultimately, the authors note, the applications of this data will be driven by the ingenuity of the scientists accessing it.

Phylogenomics and the rise of the Angiosperms, Nature (open access)

Astrobiology, Genomics,