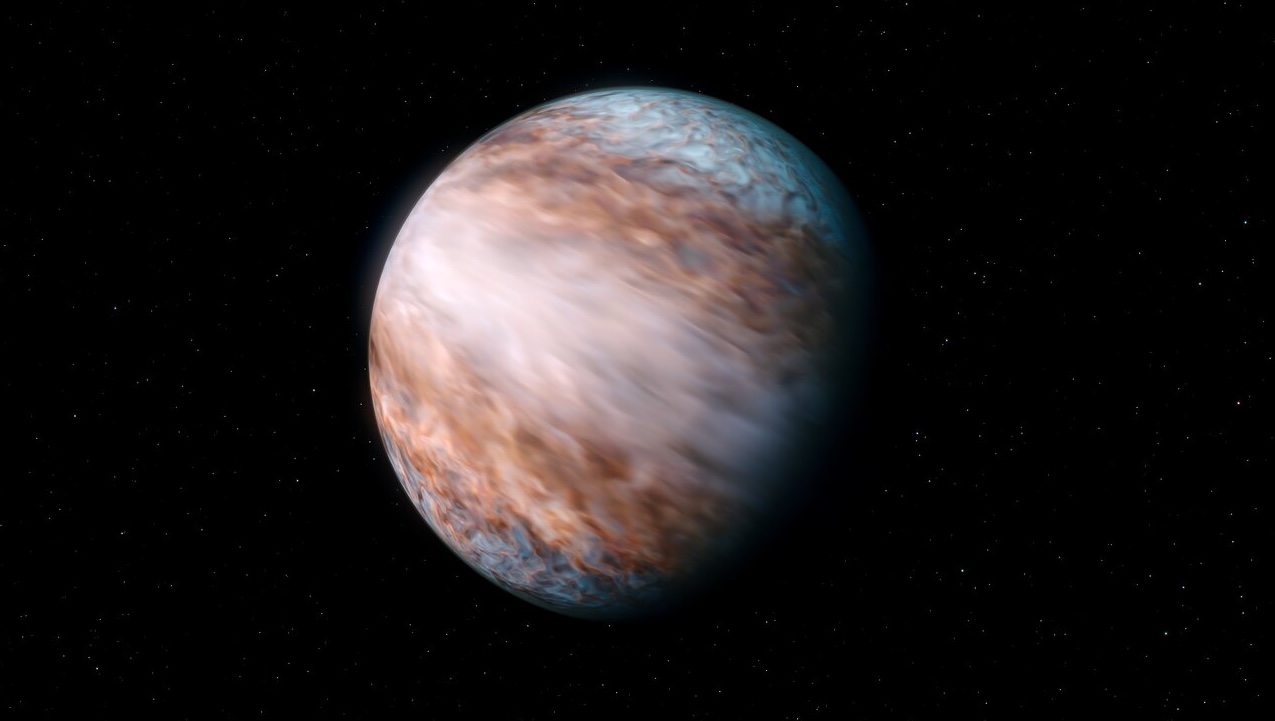

Extreme Supersonic Winds Measured On Exoplanet WASP-127b

Astronomers have discovered extremely powerful winds pummeling the equator of WASP-127b, a giant exoplanet. Reaching speeds up to 33 000 km/h, the winds make up the fastest jetstream of its kind ever measured on a planet.

The discovery was made using the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) in Chile and provides unique insights into the weather patterns of a distant world.

Tornados, cyclones and hurricanes wreak havoc on Earth, but scientists have now detected planetary winds on an entirely different scale, far outside the Solar System. Ever since its discovery in 2016, astronomers have been investigating the weather on WASP-127b, a giant gas planet located over 500 light-years from Earth. The planet is slightly larger than Jupiter, but has only a fraction of its mass, making it ‘puffy’. An international team of astronomers have now made an unexpected discovery: supersonic winds are raging on the planet.

“Part of the atmosphere of this planet is moving towards us at a high velocity while another part is moving away from us at the same speed,” says Lisa Nortmann, a scientist at the University of Göttingen, Germany, and lead author of the study. “This signal shows us that there is a very fast, supersonic, jet wind around the planet’s equator.”

At 9 km per second (which is close to a whopping 33 000 km/h), the jet winds move at nearly six times the speed at which the planet rotates [1]. “This is something we haven’t seen before,” says Nortmann. It is the fastest wind ever measured in a jetstream that goes around a planet. In comparison, the fastest wind ever measured in the Solar System was found on Neptune, moving at ‘only’ 0.5 km per second (1800 km/h).

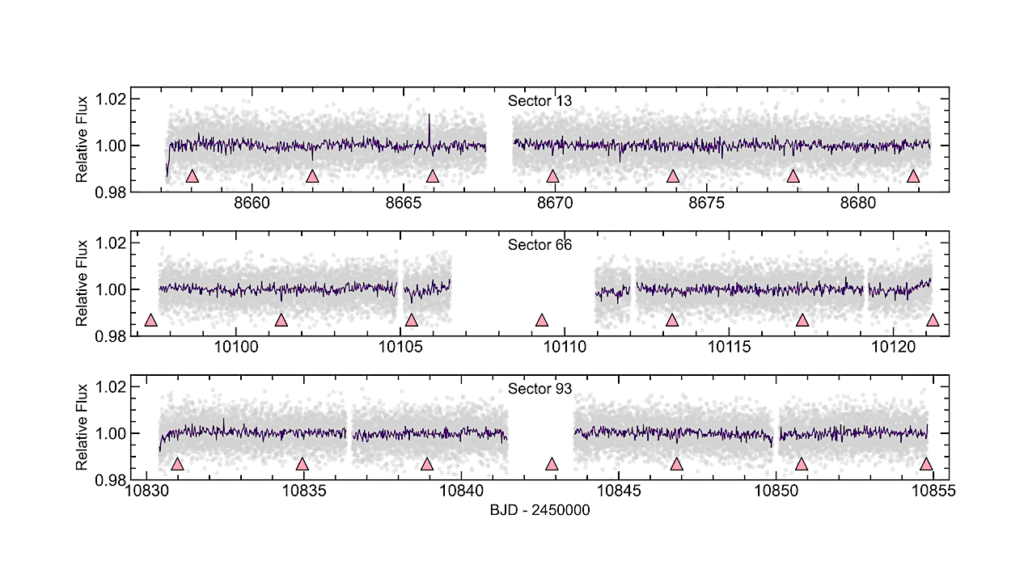

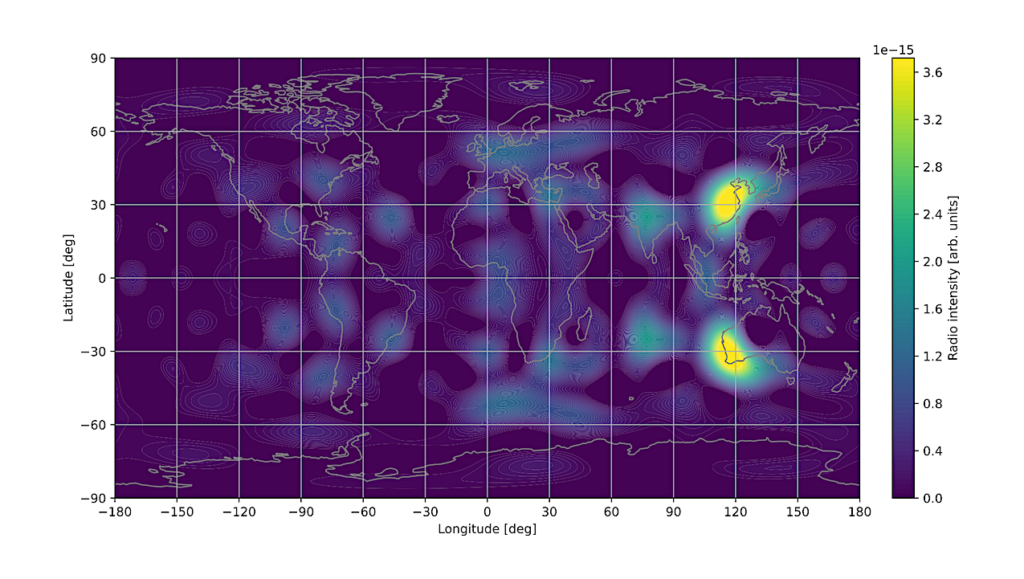

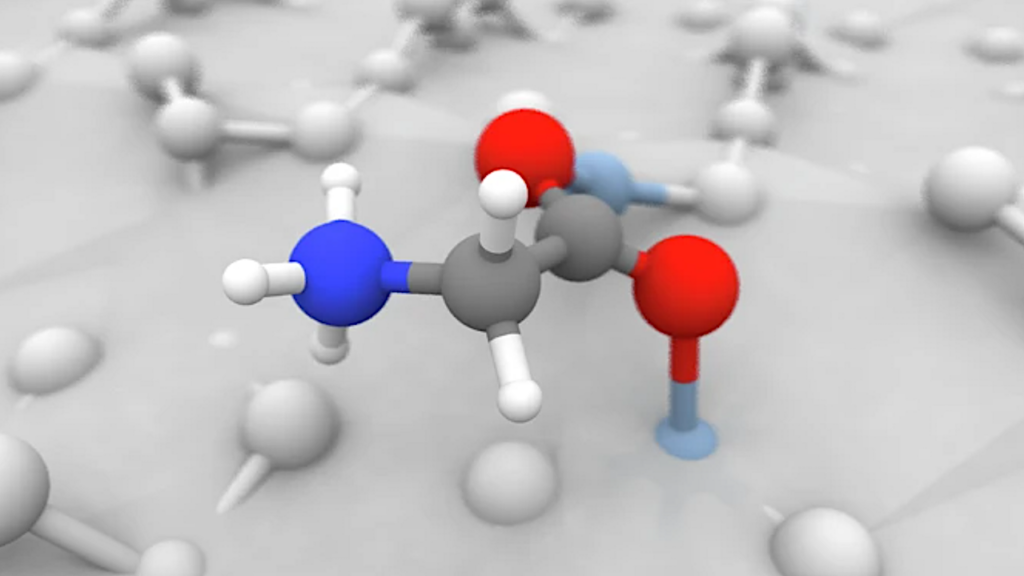

The team, whose research was published today in Astronomy & Astrophysics, mapped the weather and make-up of WASP-127b using the CRIRES+ instrument on ESO’s VLT. By measuring how the light of the host star travels through the planet’s upper atmosphere, they managed to trace its composition. Their results confirm the presence of water vapour and carbon monoxide molecules in the planet’s atmosphere.

But when the team tracked the speed of this material in the atmosphere, they observed — much to their surprise — a double peak, indicating that one side of the atmosphere is moving towards us and the other away from us at high speed. The researchers conclude that powerful jetstream winds around the equator would explain this unexpected result.

Further building up their weather map, the team also found that the poles are cooler than the rest of the planet. There is also a slight temperature difference between the morning and evening sides of WASP-127b. “This shows that the planet has complex weather patterns just like Earth and other planets of our own System,” adds Fei Yan, a co-author of the study and a professor at the University of Science and Technology of China.

The field of exoplanet research is rapidly advancing. Up until a few years ago, astronomers could measure only the mass and the radius of planets outside the Solar System. Today, telescopes like ESO’s VLT already allow scientists to map the weather on these distant worlds and analyse their atmospheres.

“Understanding the dynamics of these exoplanets helps us explore mechanisms such as heat redistribution and chemical processes, improving our understanding of planet formation and potentially shedding light on the origins of our own Solar System,” says David Cont from the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany, and a co-author of the paper.

Interestingly, at present, studies like this can only be done by ground-based observatories, as the instruments currently on space telescopes do not have the necessary velocity precision.

ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope — which is under construction close to the VLT in Chile — and its ANDES instrument will allow researchers to delve even deeper into the weather patterns on far-away planets. “This means that we can likely resolve even finer details of the wind patterns and expand this research to smaller, rocky planets,” Nortmann concludes.

Notes

[1] While the team hasn’t measured the rotation speed of the planet directly, they expect WASP-127b to be tidally locked, meaning the planet takes as long to rotate around its own axis as it does to orbit the star. Knowing how big the planet is and how long it takes to orbit its star, they can infer how fast it’s rotating.

CRIRES+ transmission spectroscopy of WASP-127 b, Astronomy & Astrophysics (open access)

Astrobiology