Away Team Update: Exploring Hydrothermal Vents In The Gulf Of California

When Samantha Joye and her fellow researchers once again set sail into the Gulf of California, they weren’t sure what to expect.

Andy Montgomery, Mandy Joye, and Ryan Sibert (L to R) pose in front of ALVIN after Sibert and Montgomery completed their first dive of the expedition. Montgomery and Sibert are former Ph.D. students in the Joye Lab and joined this expedition to continue their work in the Gulf of California. (Photo by HOV Alvin/Woods Hole Oceanographic/Mandy Joye)

Joye had been studying hydrothermal vents in the area for over 15 years—her first expedition taking place in 2009—but hadn’t returned since 2019 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

This is a hydrothermal flange in the Pescadero Basin. Flanges are created when superheated hydrothermal fluids (over 572 degrees Fahrenheit) mix with cold seawater and grow laterally as discharge continues. (Photo by HOV Alvin/Woods Hole Oceanographic/Mandy Joye)

This flange in the Guaymas Basin shows reflections of sea creatures present along the bottom “mirror” surface. The edge of the flange appears to shimmer from the temperature difference between hot fluid and cold seawater. This causes a trick of the light, giving the appearance of a mirror. For this reason, flanges are often called “mirror flanges.” (Photo by HOV Alvin/Woods Hole Oceanographic/Mandy Joye)

With help from a National Science Foundation grant, Joye led an interdisciplinary team in Spring 2024—composed of researchers from Montana State University, University of Texas at Austin, and University of Wisconsin—to the gulf aboard the research vessel Atlantis, a U.S. Navy ship operated by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution.

“When you’re on a ship, operations occur around the clock. When you’re the chief scientist, there is not much rest,” said Joye, Regents’ Professor and UGA Athletics Association Professor in the Franklin College of Arts & Sciences Department of Marine Sciences. “I would get about four hours of sleep each night, then I was back in the lab or preparing for a dive.”

The white blobs featured in this image are the microbial biofilm of Epsilonproteobacteria. These microorganisms oxidize sulfur and use the energy to support their growth. Deep sea anemones surround the biofilm. (Photo by HOV Alvin/Woods Hole Oceanographic/Mandy Joye)

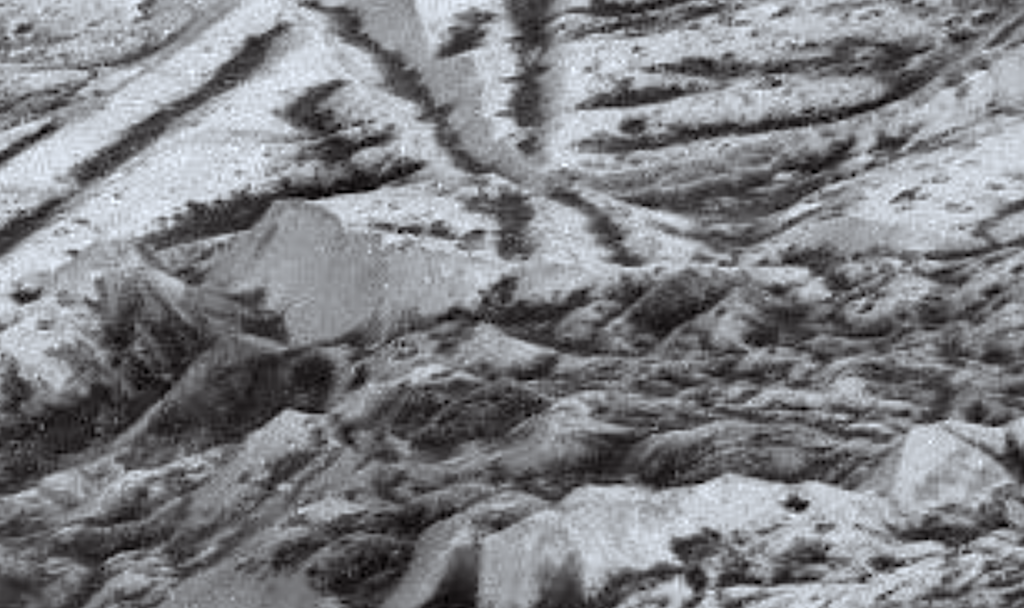

Upon finally reaching the study area, they discovered drastic changes due to many earthquakes occurring over the past five years, as well as the recent El Niño climate pattern.

“We had to start from scratch. The area had changed so much, we didn’t even recognize it,” Joye said.

The team spent three weeks at sea, investigating how recent events had affected hydrothermal systems located along the gulf’s sea floor. The hydrothermal vents release high-temperature water that creates a black “smoke” when mixed with the cold seawater.

Golden brown barite—barium sulfate—crystals can sometimes be found in hydrothermal chimneys, like this one in the Guaymas Basin. The barite precipitates as barium-rich hydrothermal fluids are diluted by sulfate-rich seawater. (Photo by Mandy Joye)

Pictured is a natural oil slick along the Sonora Margin in the Guaymas Basin. Along the Sonora Margin—indeed, throughout the Gulf of California—methane and oil seeps are abundant, and the sea surface is often marked by a rainbow sheen. (Photo by Brett Baker)

Many of these vents discharge methane gas, a highly potent greenhouse gas. Joye noted that understanding the geological and biological sources of methane in the ocean helps scientists better understand the role of the ocean in the global methane cycle and the flux of methane into the atmosphere.

The team’s discoveries were featured in the Explorers Club’s Oceans Week conference in June, and Joye is providing footage of hydrothermal vents to the upcoming “Blue Planet III” documentary, produced by the BBC.

Christelle Hyacinthe (UGA) and Valerie De Anda (University of Texas) pose with a carbonate rock collected from the “Octopus Mound” site in the Guaymas Basin. Octopus Mound is a cold seep, its name coming from an abundance of deep sea octopi at the site. (Photo by Mandy Joye)

Pictured are Riftia pachyptila (white tubes, red plumes), also known as giant tube worms. R. pachyptila have no mouth, gut, or anus; instead, they “farm” symbiotic bacteria in an internal organ called a trophosome, supplying the bacteria with oxygen, sulfide, and carbon dioxide. The orange and pink biofilm on the rock is a free-living bacteria called Beggiatoa. (Photo by Mandy Joye)

Astrobiology, oceanography,