Webb Hints At A Possible Atmosphere Surrounding Rocky Exoplanet 55 Cancri e

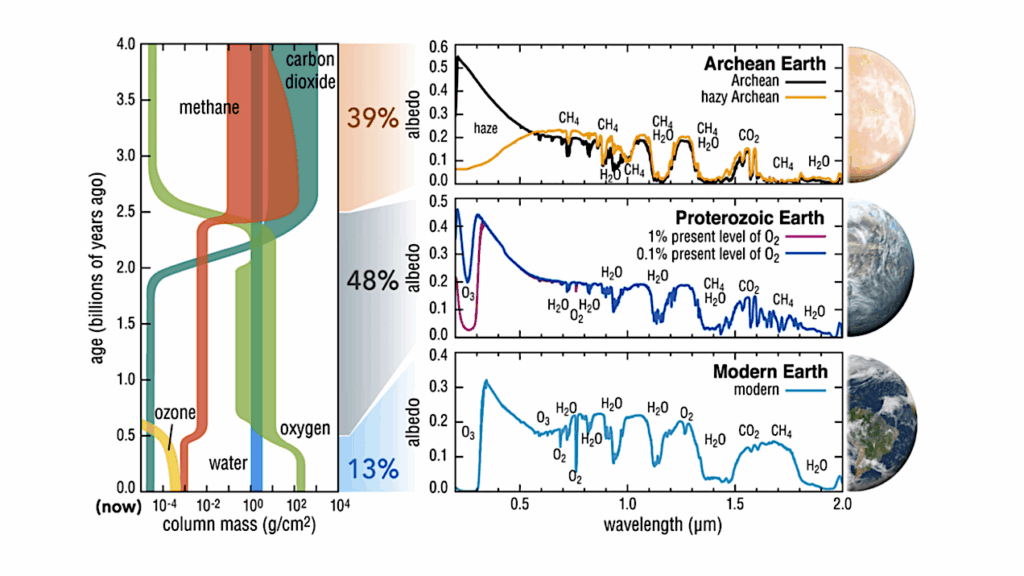

While the planet is too hot to be habitable, detecting its atmosphere could provide insights into the early conditions of Earth, Venus, and Mars.

Researchers using NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope may have detected atmospheric gases surrounding 55 Cancri e, a hot rocky exoplanet 41 light-years from Earth. This is the best evidence to date for the existence of any rocky planet atmosphere outside our solar system.

Renyu Hu from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California is lead author on a paper published today in Nature. “Webb is pushing the frontiers of exoplanet characterization to rocky planets,” Hu said. “It is truly enabling a new type of science.”

Super-Hot Super-Earth 55 Cancri e

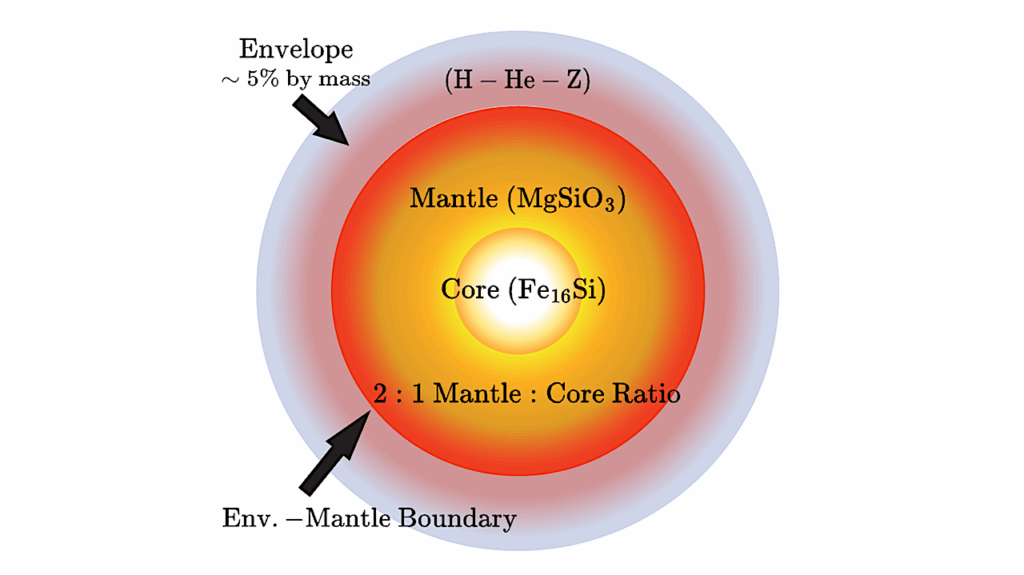

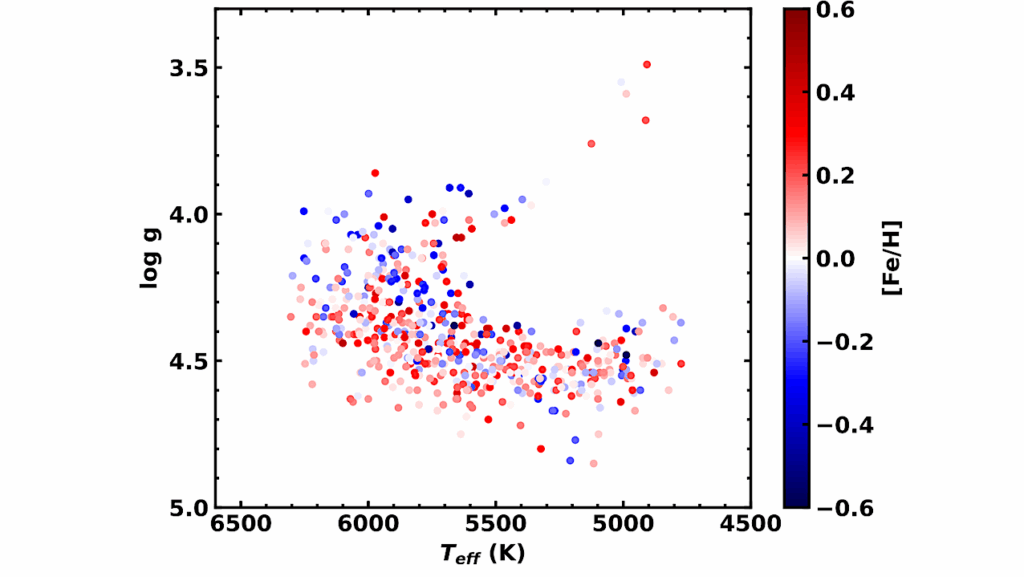

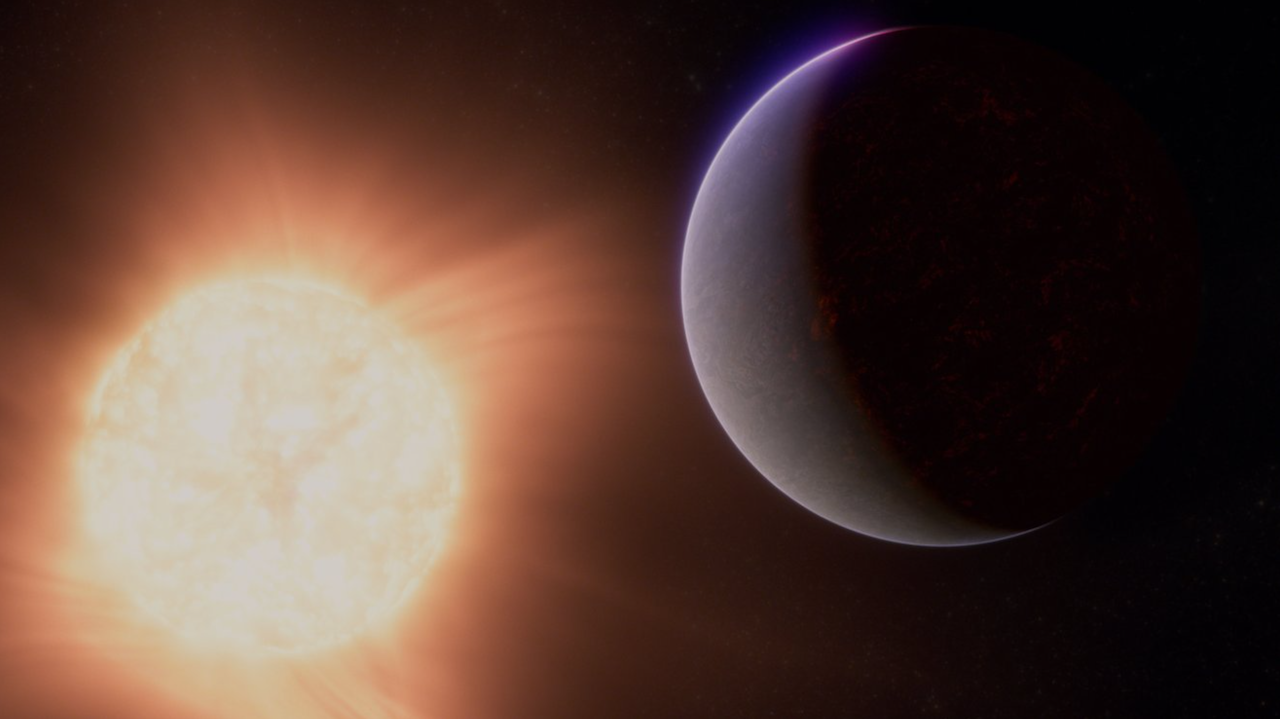

55 Cancri e, also known as Janssen, is one of five known planets orbiting the Sun-like star 55 Cancri, in the constellation Cancer. With a diameter nearly twice that of Earth and density slightly greater, the planet is classified as a super-Earth: larger than Earth, smaller than Neptune, and likely similar in composition to the rocky planets in our solar system.

Data from the Mid-Infrared Instrument on NASA’s Webb telescope shows the decrease in brightness of the 55 Cancri system as the rocky planet 55 Cancri e moves behind the star, a phenomenon known as a secondary eclipse. The data indicates that the planet’s dayside temperature is about 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI), Aaron Bello-Arufe (JPL)

To describe 55 Cancri e as “rocky,” however, could leave the wrong impression. The planet orbits so close to its star (about 1.4 million miles, or one-twenty-fifth the distance between Mercury and the Sun) that its surface is likely to be molten — a bubbling ocean of magma. With such a tight orbit, the planet is also likely to be tidally locked, with a dayside that faces the star at all times and a nightside in perpetual darkness.

In spite of numerous observations since it was discovered to transit in 2011, the question of whether or not 55 Cancri e has an atmosphere — or even could have one given its high temperature and the continuous onslaught of stellar radiation and wind from its star — has gone unanswered.

“I’ve worked on this planet for more than a decade,” said Diana Dragomir, an exoplanet researcher at the University of New Mexico and co-author on the study. “It’s been really frustrating that none of the observations we’ve been getting have robustly solved these mysteries. I am thrilled that we’re finally getting some answers!”

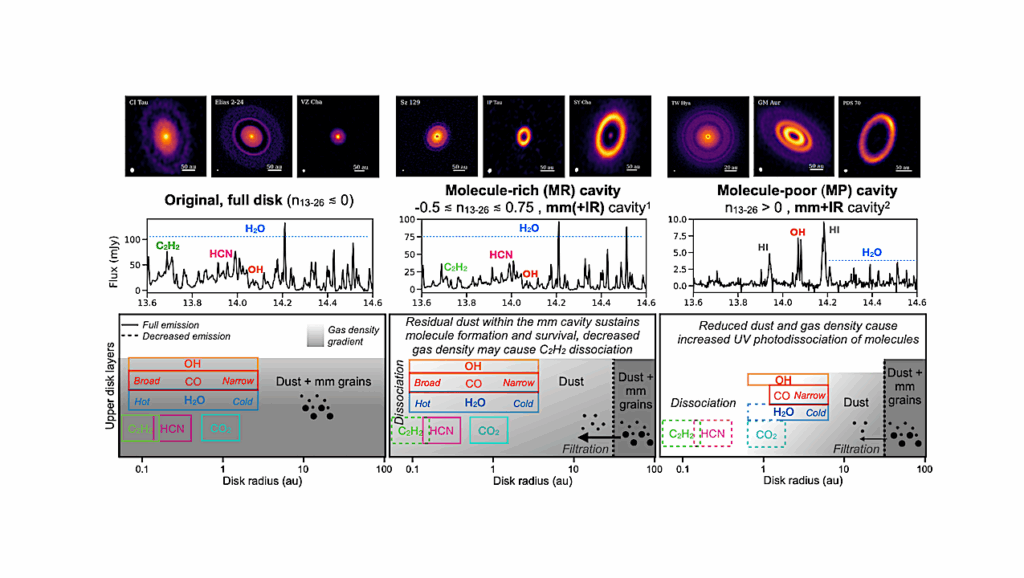

Unlike the atmospheres of gas giant planets, which are relatively easy to spot (the first was detected by NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope more than two decades ago), thinner and denser atmospheres surrounding rocky planets have remained elusive.

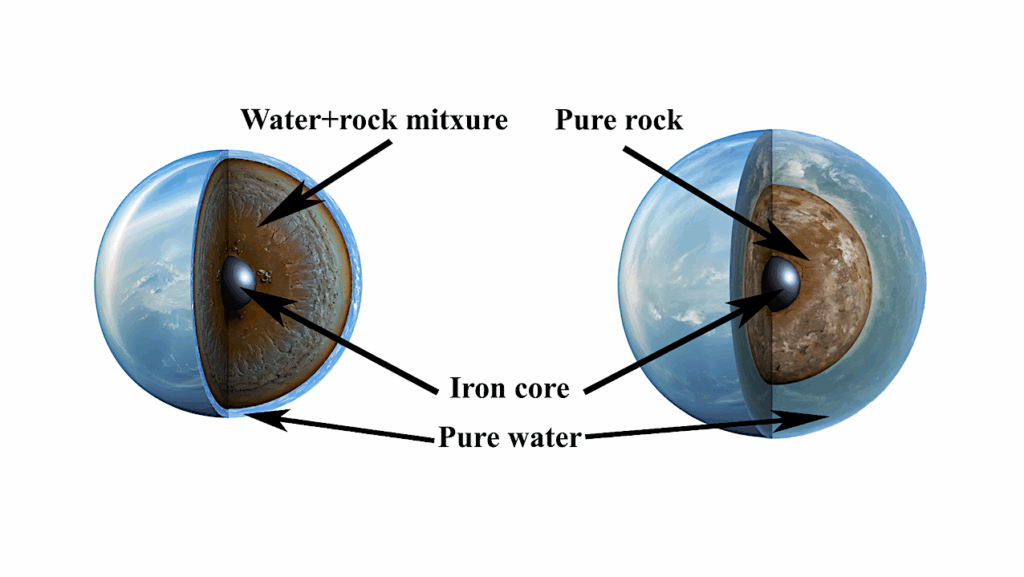

Previous studies of 55 Cancri e using data from NASA’s now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope suggested the presence of a substantial atmosphere rich in volatiles (molecules that occur in gas form on Earth) like oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. But researchers could not rule out another possibility: that the planet is bare, save for a tenuous shroud of vaporized rock, rich in elements like silicon, iron, aluminum, and calcium. “The planet is so hot that some of the molten rock should evaporate,” explained Hu.

Measuring Subtle Variations in Infrared Colors

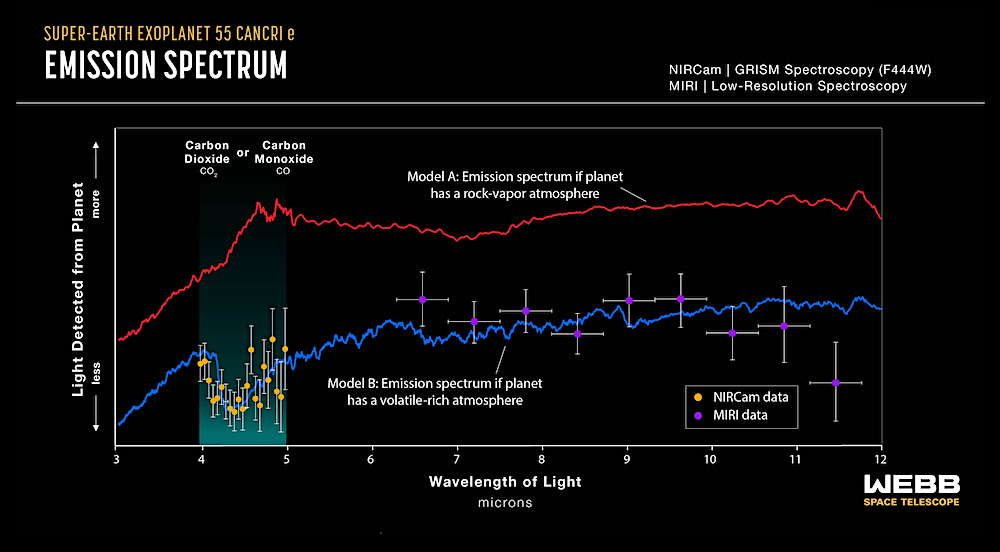

To distinguish between the two possibilities, the team used Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) to measure 4- to 12-micron infrared light coming from the planet.

A thermal emission spectrum of the exoplanet 55 Cancri e — captured by the NIRCam instrument, GRISM Spectrometer, and MIRI Low-Resolution Spectrometer on NASA’s Webb telescope — shows that the planet may be surrounded by an atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide and other volatiles. Credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Joseph Olmsted (STScI), Renyu Hu (JPL), Aaron Bello-Arufe (JPL), Michael Zhang (University of Chicago), Mantas Zilinskas (SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research)

Previous studies of 55 Cancri e using data from NASA’s now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope suggested the presence of a substantial atmosphere rich in volatiles (molecules that occur in gas form on Earth) like oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon dioxide. But researchers could not rule out another possibility: that the planet is bare, save for a tenuous shroud of vaporized rock, rich in elements like silicon, iron, aluminum, and calcium. “The planet is so hot that some of the molten rock should evaporate,” explained Hu.

Measuring Subtle Variations in Infrared Colors

To distinguish between the two possibilities, the team used Webb’s NIRCam (Near-Infrared Camera) and MIRI (Mid-Infrared Instrument) to measure 4- to 12-micron infrared light coming from the planet.

By subtracting the brightness during the secondary eclipse, when the planet is behind the star (starlight only), from the brightness when the planet is right beside the star (light from the star and planet combined), the team was able to calculate the amount of various wavelengths of infrared light coming from the dayside of the planet.

This method, known as secondary eclipse spectroscopy, is similar to that used by other research teams to search for atmospheres on other rocky exoplanets, like TRAPPIST-1 b.

Cooler Than Expected

The first indication that 55 Cancri e could have a substantial atmosphere came from temperature measurements based on its thermal emission, or heat energy given off in the form of infrared light. If the planet is covered in dark molten rock with a thin veil of vaporized rock or no atmosphere at all, the dayside should be around 4,000 degrees Fahrenheit (~2,200 degrees Celsius).

“Instead, the MIRI data showed a relatively low temperature of about 2,800 degrees Fahrenheit [~1540 degrees Celsius],” said Hu. “This is a very strong indication that energy is being distributed from the dayside to the nightside, most likely by a volatile-rich atmosphere.” While currents of lava can carry some heat around to the nightside, they cannot move it efficiently enough to explain the cooling effect.

Astrobiology