Earth’s Global Carbon Cycle Could Help Assess Liveability Of Other Planets

Research has uncovered important new insights into the evolution of oxygen, carbon, and other vital elements over the entire history of Earth – and it could help assess which other planets can develop life, ranging from plants to animals and humans.

The study, published today in Nature Geoscience and led by a researcher at the University of Bristol, reveals for the first time how the build up of carbon-rich rocks has accelerated oxygen production and its release into the atmosphere. Until now the exact nature of how the atmosphere became oxygen-rich has long eluded scientists and generated conflicting explanations.

As carbon dioxide is steadily emitted by volcanoes, it ends up entering the ocean and forming rocks like limestone. As global stocks of these rocks build up they can then release their carbon during tectonic processes, including mountain building and metamorphism.

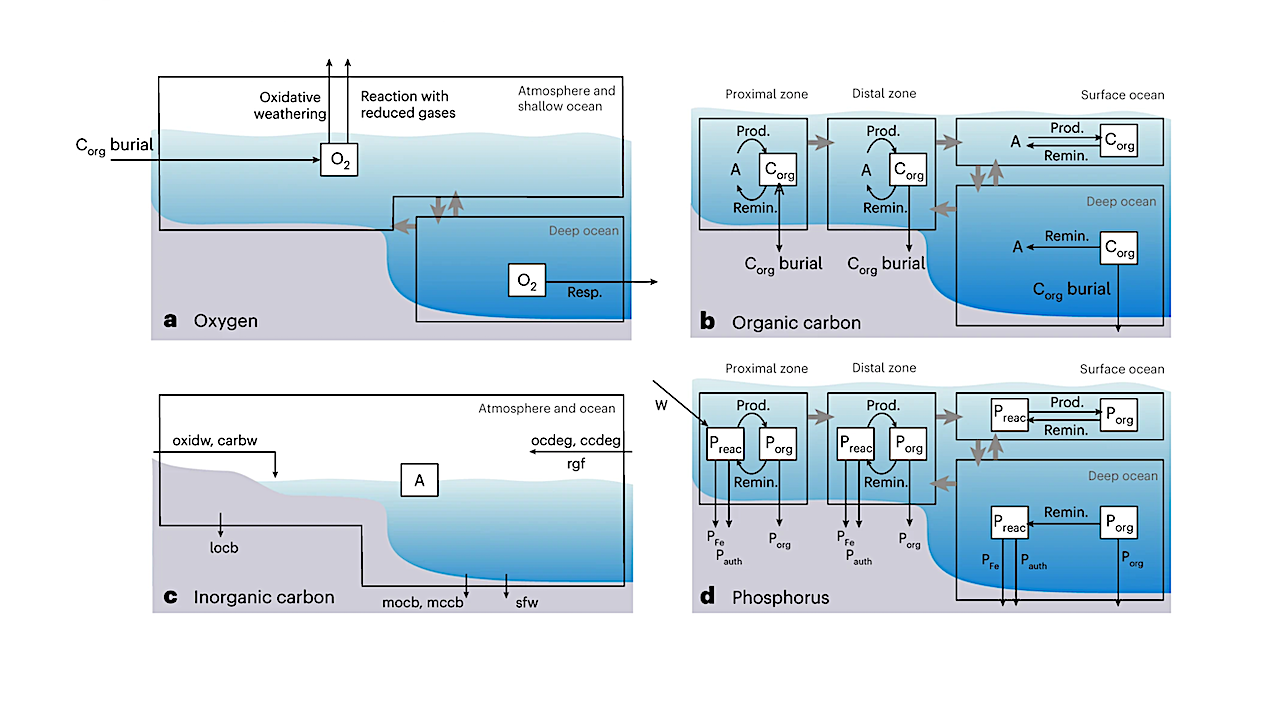

Using this knowledge, the scientists built a unique sophisticated computer model to more accurately chart key changes in the carbon, nutrient and oxygen cycles deep into Earth’s history, over 4 billion years of the planet’s lifetime.

Lead author and biogeochemist Dr Lewis Alcott, Lecturer in Earth Sciences at the University of Bristol, said: “This breakthrough is important and exciting because it may help us understand how planets, other than Earth, have the potential to support intelligent, oxygen-breathing life.

“Previously we didn’t have a clear idea of why oxygen rose from very low concentrations to present-day concentrations, as computer models haven’t previously been able to accurately simulate all the possible feedbacks together. This has puzzled scientists for decades and created different theories.”

The discovery indicates that older planets, originating billions of years ago like Earth, may have better prospects to accumulate enough carbon-rich deposits in their crust, which could facilitate rapid recycling of carbon and nutrients for life.

The findings showed this gradual carbon enrichment of the crust results in ever-increasing recycling rates of carbon and various minerals, including the nutrients needed for photosynthesis, the process green plants use sunlight to absorb nutrients from carbon dioxide and water. This cycle therefore steadily speeds up oxygen production over the passage of Earth’s history.

The research, which started whilst Dr Alcott was a Hutchinson Postdoctoral Fellow at Yale University in the United States, paves the way for future work to further unravel the complex interrelationships between planetary temperature, oxygen, and nutrients.

Co-author Prof Benjamin Mills, Professor of Earth System Evolution at the University of Leeds, said: “We have lots of information about distant stars and the size of the planets that orbit them. Soon this could be used to make a prediction of the planet’s potential chemistry, and new advances in telescope technology should let us know if we are correct.”

Crustal carbonate build-up as a driver for Earth’s oxygenation, Nature Geoscience (open access)

Astrobiology,