Can A Planet Have A Mind Of Its Own?

The collective activity of life–all of the microbes, plants, and animals–have changed planet Earth.

Take, for example, plants: plants ‘invented’ a way of undergoing photosynthesis to enhance their own survival, but in so doing, released oxygen that changed the entire function of our planet. This is just one example of individual lifeforms performing their own tasks, but collectively having an impact on a planetary scale.

If the collective activity of life–known as the biosphere–can change the world, could the collective activity of cognition, and action based on this cognition, also change a planet? Once the biosphere evolved, Earth took on a life of its own. If a planet with life has a life of its own, can it also have a mind of its own?

These are questions posed by Adam Frank, the Helen F. and Fred H. Gowen Professor of Physics and Astronomy at the University of Rochester, and his colleagues David Grinspoon at the Planetary Science Institute and Sara Walker at Arizona State University, in a paper published in the International Journal of Astrobiology. Their self-described “thought experiment” combines current scientific understanding about the Earth with broader questions about how life alters a planet. In the paper, the researchers discuss what they call “planetary intelligence”–the idea of cognitive activity operating on a planetary scale–to raise new ideas about the ways in which humans might tackle global issues such as climate change.

As Frank says, “If we ever hope to survive as a species, we must use our intelligence for the greater good of the planet.”

An ‘immature technosphere’

Frank, Grinspoon, and Walker draw from ideas such as the Gaia hypothesis–which proposes that the biosphere interacts strongly with the non-living geological systems of air, water, and land to maintain Earth’s habitable state–to explain that even a non-technologically capable species can display planetary Intelligence. The key is that the collective activity of life creates a system that is self-maintaining.

For example, Frank says, many recent studies have shown how the roots of the trees in a forest connect via underground networks of fungi known as mycorrhizal networks. If one part of the forest needs nutrients, the other parts send the stressed portions the nutrients they need to survive, via the mycorrhizal network. In this way, the forest maintains its own viability.

Right now, our civilization is what the researchers call an “immature technosphere,” a conglomeration of human-generated systems and technology that directly affects the planet but is not self-maintaining. For instance, the majority of our energy usage involves consuming fossil fuels that degrade Earth’s oceans and atmosphere. The technology and energy we consume to survive are destroying our home planet, which will, in turn, destroy our species.

To survive as a species, then, we need to collectively work in the best interest of the planet.

But, Frank says, “we don’t yet have the ability to communally respond in the best interests of the planet. There is intelligence on Earth, but there isn’t planetary intelligence.”

Toward a mature technosphere

The researchers posit four stages of Earth’s past and possible future to illustrate how planetary intelligence might play a role in humanity’s long-term future. They also show how these stages of evolution driven by planetary intelligence may be a feature of any planet in the galaxy that evolves life and a sustainable technological civilization.

Stage 1 – Immature biosphere: characteristic of very early Earth, billions of years ago and before a technological species, when microbes were present but vegetation had not yet come about. There were few global feedbacks because life couldn’t exert forces on Earth’s atmosphere, hydrosphere, and other planetary systems.

Stage 2 – Mature biosphere: characteristic of Earth, also before a technological species, from about 2.5 billion to 540 million years ago. Stable continents formed, vegetation and photosynthesis developed, oxygen built up in the atmosphere, and the ozone layer emerged. The biosphere exerted a strong influence on the Earth, perhaps helping to maintain Earth’s habitability.

Stage 3 – Immature technosphere: characteristic of Earth now, with interlinked systems of communication, transportation, technology, electricity, and computers. The technosphere is still immature, however, because it is not integrated into other Earth systems, such as the atmosphere. Instead, it draws matter and energy from Earth’s systems in ways that will drive the whole into a new state that likely doesn’t include the technosphere itself. Our current technosphere is, in the long run, working against itself.

Stage 4 – Mature technosphere: where Earth should aim to be in the future, Frank says, with technological systems in place that benefit the entire planet, including globally harvesting energy in forms like solar that do not harm the biosphere. The mature technosphere is one that has co-evolved with the biosphere into a form that allows both the technosphere and the biosphere to thrive.

“Planets evolve through immature and mature stages, and planetary intelligence is indicative of when you get to a mature planet,” Frank says. “The million-dollar question is figuring out what planetary intelligence looks like and means for us in practice because we don’t know how to move to a mature technosphere yet.”

The complex system of planetary intelligence

Although we don’t yet know specifically how planetary intelligence might manifest itself, the researchers note that a mature technosphere involves integrating technological systems with Earth through a network of feedback loops that make up a complex system.

Put simply, a complex system is anything built from smaller parts that interact in such a fashion that the overall behavior of the system is entirely dependent on the interaction. That is, the sum is more than the whole of its parts. Examples of complex systems include forests, the Internet, financial markets, and the human brain.

By its very nature, a complex system has entirely new properties that emerge when individual pieces are interacting. It is difficult to discern the personality of a human being, for instance, solely by examining the neurons in her brain.

That means it is difficult to predict exactly what properties might emerge when individuals form a planetary intelligence. However, a complex system like planetary intelligence will, according to the researchers, have two defining characteristics: it will have emergent behavior and will need to be self-maintaining.

“The biosphere figured out how to host life by itself billions of years ago by creating systems for moving around nitrogen and transporting carbon,” Frank says. “Now we have to figure out how to have the same kind of self-maintaining characteristics with the technosphere.”

The search for extraterrestrial life

Despite some efforts, including global bans on certain chemicals that harm the environment and a move toward using more solar energy, “we don’t have planetary intelligence or a mature technosphere yet,” he says. “But the whole purpose of this research is to point out where we should be headed.”

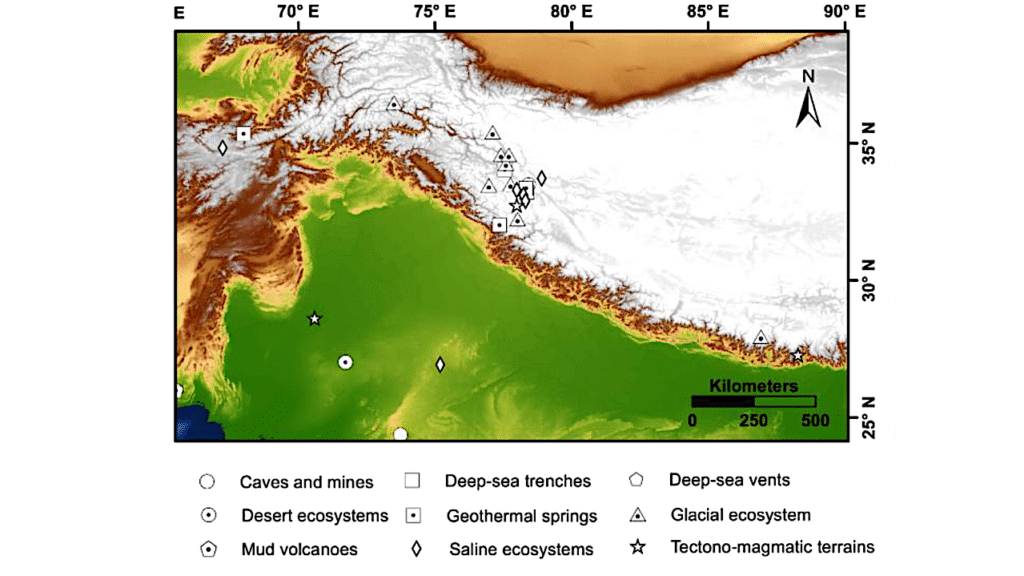

Raising these questions, Frank says, will not only provide information about the past, present, and future survival of life on Earth but will also help in the search for life and civilizations outside our solar system. Frank, for instance, is the principal investigator on a NASA grant to search for technosignatures of civilizations on planets orbiting distant stars.

“We’re saying the only technological civilizations we may ever see–the ones we should expect to see–are the ones that didn’t kill themselves, meaning they must have reached the stage of a true planetary intelligence,” he says. “That’s the power of this line of inquiry: it unites what we need to know to survive the c

limate crisis with what might happen on any planet where life and intelligence evolve.”

Intelligence as a planetary scale process, International Journal of Astrobiology

Astrobiology