Extreme Environment of Danakil Depression Sheds Light on Mars, Titan

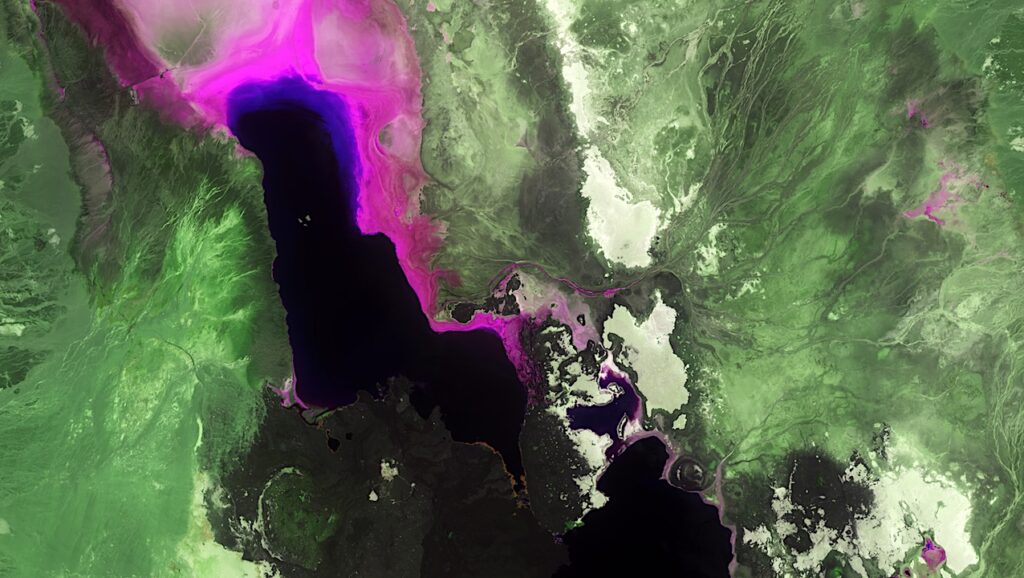

The Danakil Depression in Ethiopia is a spectacular, hostile environment that may resemble conditions encountered on Mars and Titan — as well as in sites containing nuclear waste.

From 20 to 28 January 2018, five teams of researchers and more than 30 support staff visited two locations in the region to study the microbiology, geology, and chemistry at the Dallol hydrothermal outcrop and the saline Lake Afrera.

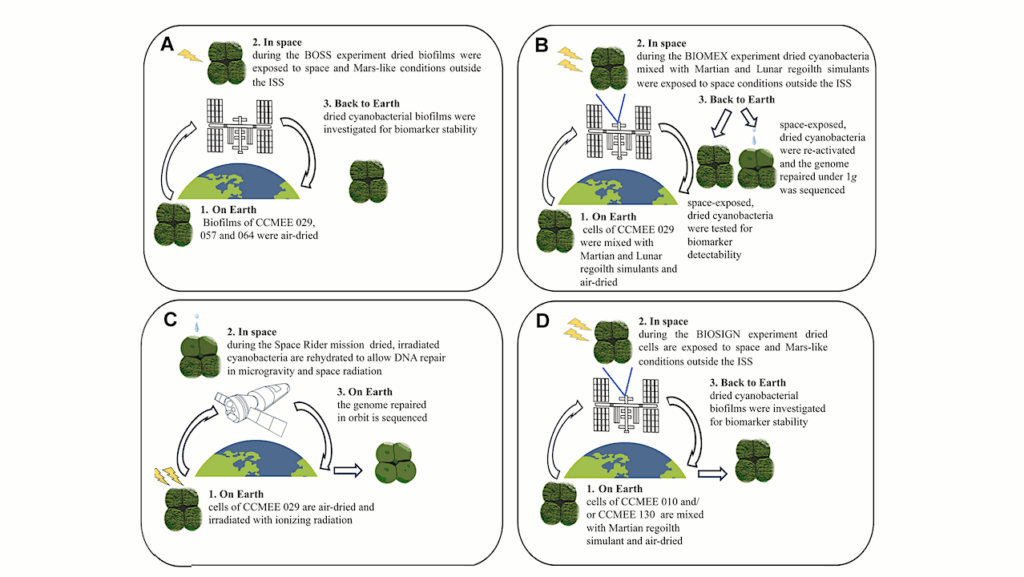

The research trip was supported by the EU-funded Europlanet 2020 Research Infrastructure (RI), which has organised a series of field campaigns over the past two years to characterise the site as an analogue for other planetary surfaces and for astrobiological studies.

Dallol is a uniquely hostile place for life due to the combination of its extreme salinity, high temperature, and acidity. It is one of the hottest places on Earth, at more than 100 metres below sea level. Upwelling water, rich in many different salts and heated by magma close to the surface, forms brightly-coloured, highly acidic pools. Toxic gases, including chlorine and sulphur vapour, hang in the air.

Karen Olsson-Francis and Vincent Rennie from the Open University are studying how microbiology is affected by variation in the physical and chemical conditions at Dallol, and where pockets of habitability might be found. They focused on two channels of highly acidic, saline water with temperatures ranging from 40 to 70°C. The pair took measurements on-site and collected samples for further analysis in the laboratory.

“Our initial findings showed that microbes may be present, despite the extreme salinity and acidity,” said Rennie. The team will now undertake further geological and microbial analysis in the coming months and hope to have preliminary results of the outflow channel study by early September.

Hugo Moors and Mieke De Craen of SCK-CEN also studied microbiology in the context of the geology and the chemistry of the water at a number of locations, and successfully tested a range of new sampling techniques and sample preservation systems. In addition to their astrobiology research related to exoplanets, the pair are using Danakil as an analogue for nuclear waste.

“The extreme conditions in the Danakil Depression might resemble some of the conditions encountered in the disposal of waste from nuclear reactors. We will now try to cultivate microbes and chemically analyse samples of the water from Danakil to attempt to understand what might be able to survive in nuclear waste,” said Moors.

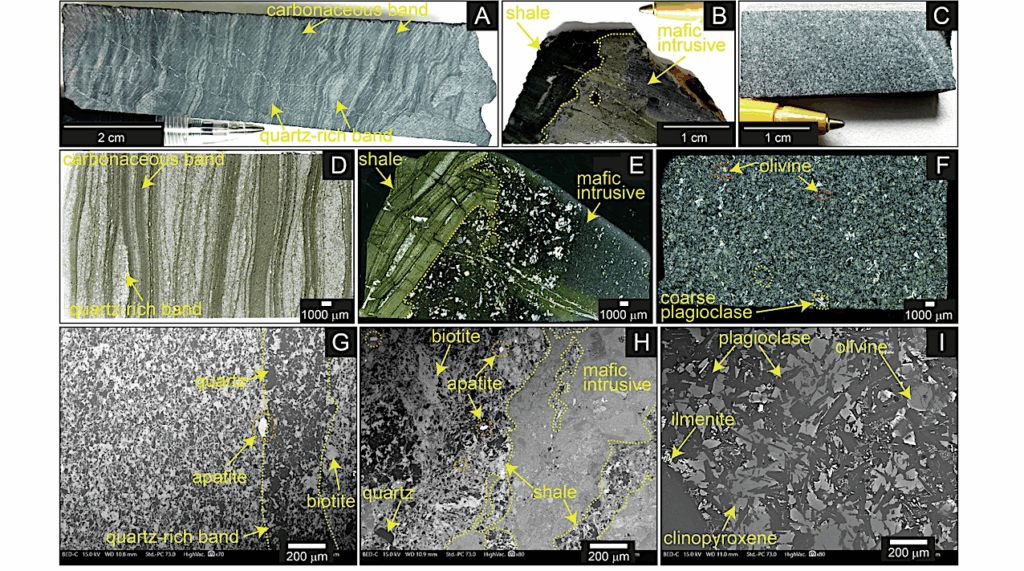

Next summer, the ExoMars Trace Gas Orbiter will begin a study of rift zones on Mars, which are characterised by salt deposits and ancient magma systems and have strong similarities to the Afar rift currently forming between the Erta Ale and Dallol volcanoes. To support the upcoming mission observations, Daniel Mège of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Ernst Hauber of DLR carried out a preliminary study of the structure of hydrothermal systems and took soil samples from several centimetres below the surface to determine microbial life present.

“We need to analyse our findings, but some of the preliminary results look very exciting,” said Mège. “We’ve also carried out reconnaissance work for a ground magnetic survey next year, in which we aim to characterise intrusive magmatic activity in the rift. We look forward to returning in 2019.”

Jani Radebaugh of Brigham Young University, with Ralph Lorenz of the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, used a handheld digital camera and ‘kite-cam’, a kite-lofted GoPro, to create image-derived Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) at a variety of locations across the playas and other regions in the Afar. They have gathered 15 different image datasets at a variety of locations, which they will then compare to RADAR data on the roughness of the terrain.

“This region is absolutely spectacular for field work from a planetary perspective, as there are so many unusual and extreme environments that have strong planetary analogues,” said Radebaugh. “The comparison of our datasets gathered on the ground with RADAR images taken from space, which quantify roughness in a different way, will help us interpret data from space missions on the roughness of surfaces at Titan and Mars.”

David Vaz and Lourenço Bandeira of the Centre for Earth and Space Research of the University of Coimbra surveyed the shape, subsurface geometry and ages of fault scarps on a rift located south of Lake Afrera. Understanding how erosion degrades these volcanic structures in very arid environments on Earth will enable them to interpret similar features on Mars and infer erosion rates throughout the Red Planet’s geological history.

Vaz said: “When you spend several years at a computer, looking at images from the surface of Mars and trying to understand what happened there, it’s easy to lose the sense of scale. Going to the field, and actually seeing things with your own eyes gives you a more real perspective on what you are dealing with. To achieve our purpose of using fault scarps as paleo-environmental markers on Mars, it would be great to survey other faults, with different ages and presenting different states of preservation. On this trip, the geophysical instruments that should give a perspective on the underground fault geometry did not work, but that’s the price we pay when working in such remote and difficult conditions. We hope to return to the site to carry out further studies.”

Felipe Gomez, Nuria Rodriguez and Beatriz Flores of CAB-INTA worked on the preparation of the Danakil site as a planetary analogue for Europlanet 2020 RI’s transnational access programme, which provides funding for researchers to visit the site and carry out experiments.

“The diversity of the research carried out by these five teams shows the versatility of this exotic landscape for planetary research,” said Gomez. “We have already had interesting findings about the preservation of organic matter under such harsh conditions, which gives important clues about martian habitability. Any scientist can now apply to carry out planetary experiments at Danakil. We look forward to seeing the results!”

“In visiting Danakil, we have purposely brought together people from different parts of the world to encourage the sharing of ideas across institutions, countries and continental boundaries,” said Gian Gabriele Ori of the International Research School of Planetary Sciences in Pescara, who led the expedition. “Seasoned researchers have worked side by side and shared their experience with young scientists. It has been a very successful trip.”

The expedition was supported by Monica Bufill and Daniela D’Alleva of the International Research School of Planetary Sciences in Pescara, Italy, Miruts Hagos from Mekelle University and Mikael Tamrat and Zablon Beyene of Zab Tours Ethiopia. The team was accompanied by the photographer, Alex Pritz.