Cosmic Radiation From A Supernova Altered Virus Evolution In Africa, Study Proposes

Isolated by mountains along the East African Rift is Lake Tanganyika. Over 400 miles long, it is the continent’s deepest lake and accounts for 16% of the world’s available freshwater. Between two and three million years ago, the number of virus species infecting fish in that immense lake exploded, and in a new study, UC Santa Cruz researchers propose that this explosion was perhaps triggered by the explosion of a distant star.

The new paper, led by recent undergraduate student Caitlyn Nojiri and co-authored by astronomy and astrophysics professor Enrico Ramirez-Ruiz and postdoctoral fellow Noémie Globus, examined iron isotopes to identify a 2.5 million-year-old supernova.

The researchers connected this stellar explosion to a surge of radiation that pummeled Earth around the same time, and they assert that the blast was powerful enough to break the DNA of living creatures—possibly driving those viruses in Lake Tanganyika to mutate into new species. Their paper was published on January 15 in the journal Astrophysical Journal Letters.

“It’s really cool to find ways in which these super distant things could impact our lives or the planet’s habitability,” said Nojiri (2024, physics [astrophysics], mathematical theory and computation).

From deep space to ocean floor

Their research started on the seafloor, where a radioactive form of iron produced by exploding stars is found. They aged the element, known as iron-60, by seeing how much of it had already broken down into nonradioactive forms. The iron-60 was actually of two different ages. Some formed 2.5 million years ago, while other atoms were 6.5 million years old.

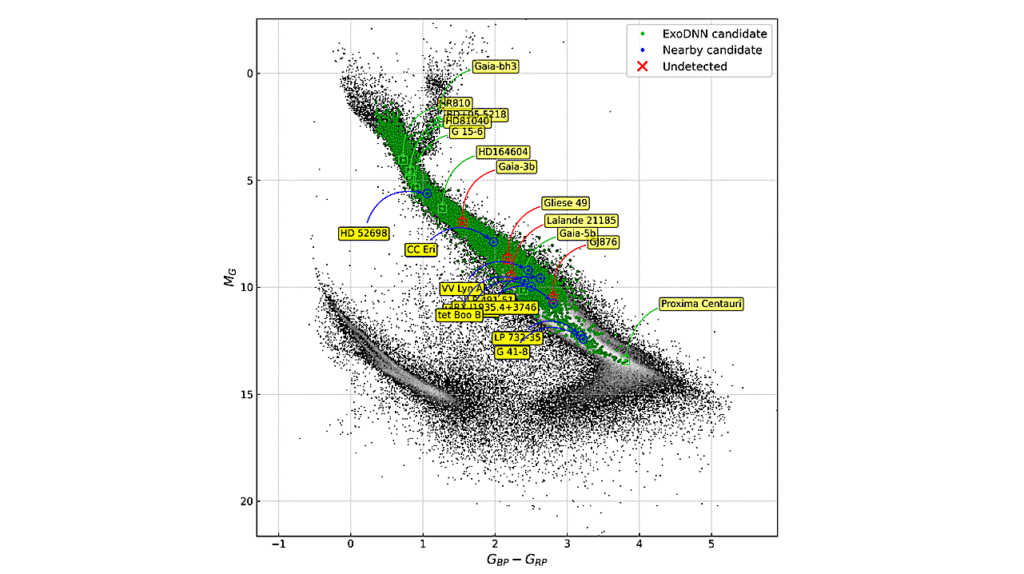

They then sleuthed the origin of the iron by backtracking the past movements of celestial bodies. Right now, our solar system is in the middle of a massive patch of relatively open space called the Local Bubble.

The Earth entered the bubble and passed through its stardust-rich exterior about 6.5 million years ago, which seeded the planet with the older iron-60. Then between 2 and 3 million years ago, one of our neighboring stars exploded with tremendous force, providing our planet with the other cohort of radioactive iron.

“The iron-60 is a way to trace back when the supernovae were occurring,” Nojiri said. From two to three million years ago, we think that a supernova happened nearby.”

Cosmic correlation to mutations

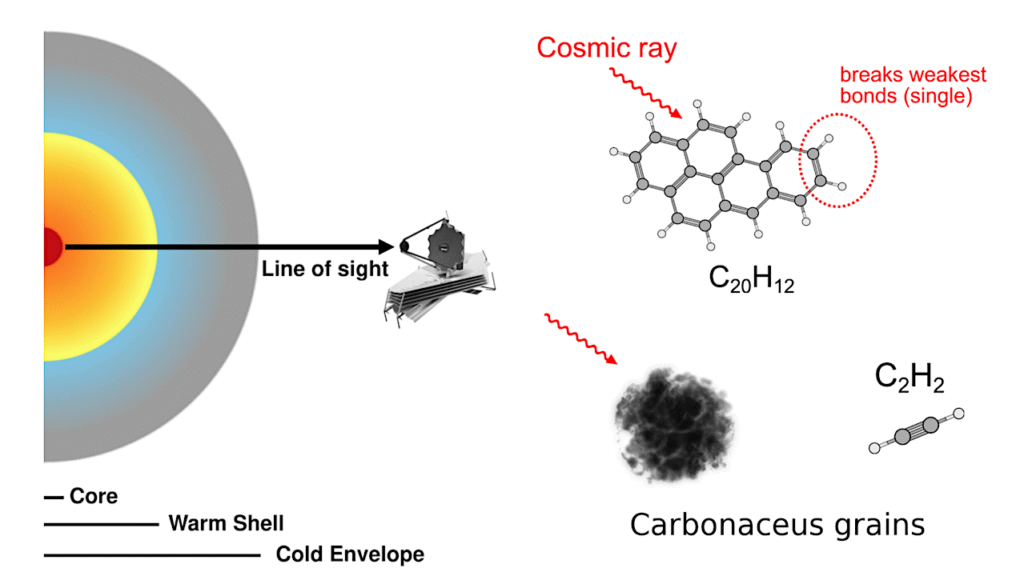

When Nojiri and colleagues simulated what that supernova was like, they found that it hammered the Earth with cosmic rays for 100,000 years following the blast. The model perfectly explained a previously recorded spike in radiation impacting Earth around that time, which had been puzzling astronomers for years.

“She was invited to give a CCAPP Seminar at Ohio State just after the paper came out,” said Ramirez-Ruiz, adding that Nojiri was the first UC Santa Cruz undergraduate to ever be invited to give a talk in that important venue.

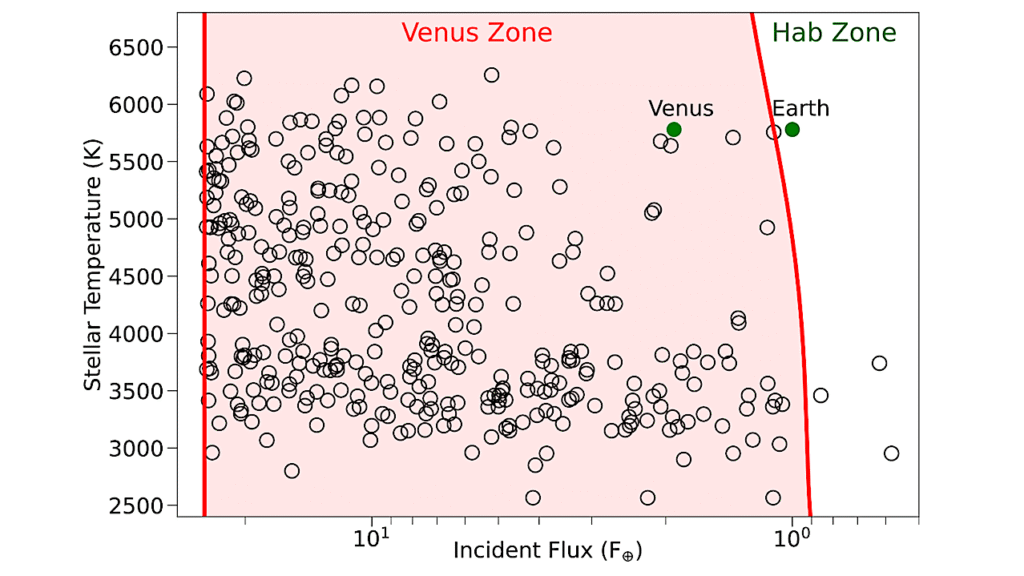

Their supernova simulation raised other questions because its cosmic rays likely bombarded Earth with enough intensity to snap strands of DNA in half. “We saw from other papers that radiation can damage DNA,” Nojiri said. “That could be an accelerant for evolutionary changes or mutations in cells.”

Meanwhile, the authors came upon a study of virus diversity in one of Africa’s Rift Valley lakes. “We can’t say that they are connected, but they have a similar timeframe,” Nojiri said. “We thought it was interesting that there was an increased diversification in the viruses.”

The value of diverse voices

Nojiri did not initially set out to be a published astronomer. “I was at community college for a long time, and I didn’t know what I wanted to do,” she said.

Nojiri eventually made her way to UC Santa Cruz, where Ramirez-Ruiz pushed her to apply for UC LEADS, a program that helps students from underrepresented groups succeed in science. “Enrico walked me to the STEM diversity office,” Nojiri said.

She also took part in Lamat, a program founded by Ramirez-Ruiz that teaches students from nontraditional backgrounds how to do research in astronomy.

“People from different walks of life bring different perspectives to science and can solve problems in very different ways,” Ramirez-Ruiz said. “This is an example of the beauty of having different perspectives in physics and the importance of having those voices.”

These programs have been a huge help for Nojiri, who is currently applying for graduate school. “I want to get a Ph.D. in astrophysics,” she said.

Life in the Bubble: How a Nearby Supernova Left Ephemeral Footprints on the Cosmic-Ray Spectrum and Indelible Imprints on Life (open access)

Astrobiology,