What Gave The First Molecules Their Stability?

The origins of life remain a major mystery. How were complex molecules able to form and remain intact for prolonged periods without disintegrating? A team at ORIGINS, a Munich-based Cluster of Excellence, has demonstrated a mechanism that could have enabled the first RNA molecules to stabilize in the primordial soup. When two RNA strands combine, their stability and lifespan increase significantly.

In all likelihood, life on Earth began in water, perhaps in a tide pool that was cut off from seawater at low tide but flooded by waves at high tide. Over billions of years, complex molecules like DNA, RNA and proteins formed in this setting before, ultimately, the first cells emerged. To date, however, nobody has been able to explain exactly how this happened.

“We know which molecules existed on the early earth,” says Job Boekhoven, Professor of Supramolecular Chemistry at the Technical University of Munich (TUM). “The question is: Can we use this to replicate the origins of life in the lab?” The team led by Boekhoven at the ORIGINS Cluster of Excellence is primarily interested in RNA. “RNA is a fascinating molecule,” says Boekhoven. “It can store information and also catalyze biochemical reactions.” Scientists therefore believe that RNA must have been the first of all complex molecules to form.

The problem, however, is that active RNA molecules are composed of hundreds or even thousands of bases and are very unstable. When immersed in water, RNA strands quickly break down into their constituent parts – a process known as hydrolysis. So, how could RNA have survived in the primordial soup?

How did double strands form in the primordial soup?

In laboratory testing, the researchers from TUM and LMU used a model system of RNA bases that join together more easily than naturally occurring bases in our cells today. “We didn’t have millions of years available and wanted an answer quickly,” explains Boekhoven. The team added these fast-joining RNA bases into a watery solution, provided an energy source and examined the length of the RNA molecules that formed. Their findings were sobering, as the resulting strands of up to five base pairs only survived for a matter of minutes.

The results were different, however, when the researchers started by adding short strands of pre-formed RNA. The free complementary bases quickly joined with this RNA in a process called hybridization. Double strands of three to five base pairs in length formed and remained stable for several hours. “The exciting part is that double strands lead to RNA folding, which can make the RNA catalytically active,” explains Boekhoven. Double-stranded RNA therefore has two advantages: it has an extended lifespan in the primordial soup and serves as the basis for catalytically active RNA.

But how could a double strand have formed in the primordial soup? “We’re currently exploring whether it’s possible for RNAs to form their own complementary strand,” says Boekhoven. It is conceivable for a molecule comprising three bases to join with a molecule comprising three complementary bases – the product of which would be a stable double-strand. Thanks to its prolonged lifespan, further bases could join with it and the strand would grow.

Evolutionary advantage for protocells

Another characteristic of double-stranded RNA could have helped bring about the origin of life. It is firstly important to note that RNA molecules can also form protocells. These are tiny droplets with an interior fully separated from the outside world. Yet, these protocells do not have a stable cell membrane and so easily merge with other protocells, which causes their contents to mix. This is not conducive to evolution because it prevents individual protocells from developing a unique identity. However, if the borders of these protocells are composed of double-stranded DNA, the cells become more stable and merging is inhibited.

Insights also applicable to medicine

In the future, Job Boekhoven hopes to further improve understanding of the formation and stabilization of the first RNA molecules. “Some people regard this research as a sort of hobby. During the Covid-19 pandemic, though, everyone saw how important RNA molecules can be, including for vaccines,” says Boekhoven. “So, while our research is striving to answer one of the oldest questions in science, that’s not all: we’re also generating knowledge about RNA that could benefit many people today.”

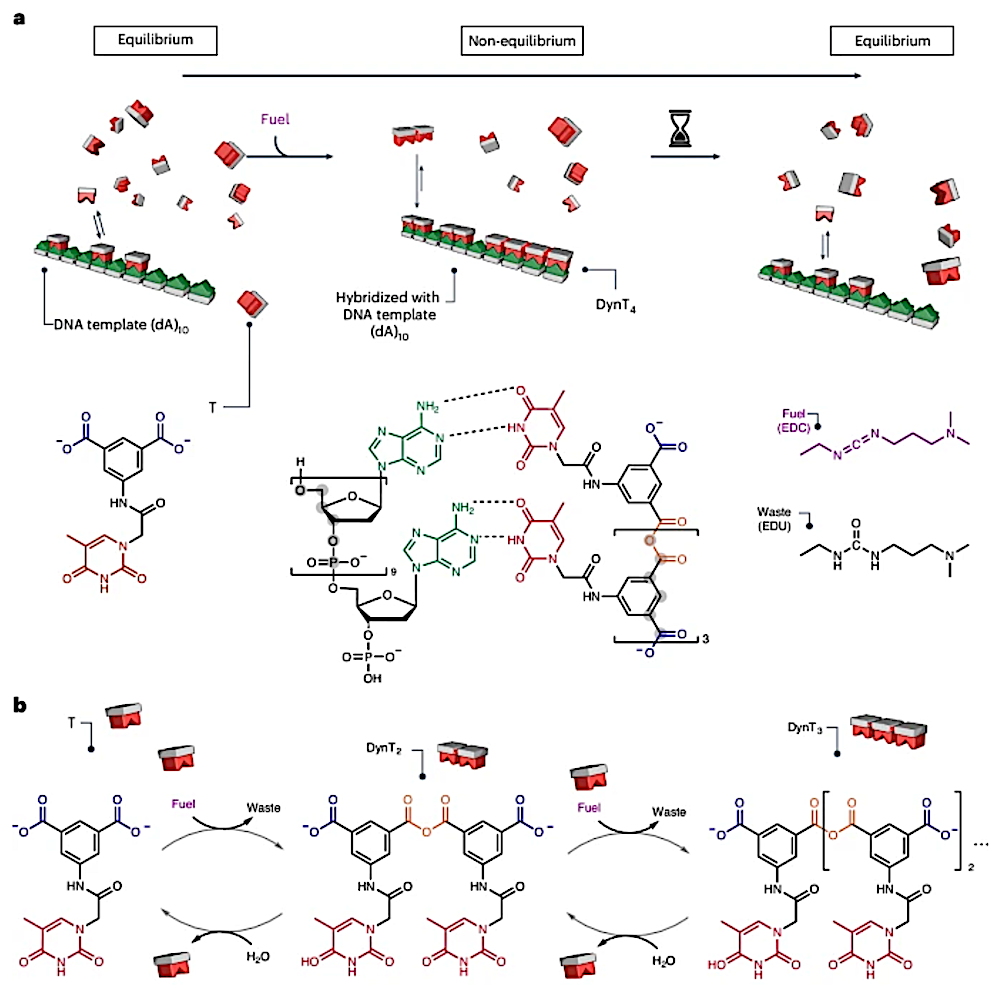

a, Schematic representation of the concept of the chemically fuelled dynamic combinatorial library and the role of the template. Oligomers interact with the template. The six-atom repeating backbone unit of DNA and the oligomers (highlighted with grey shading) match. The molecular structures of the DNA template (dA)10, thymine-labelled monomer T and its oligomers, fuel 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)carbodiimide (EDC) and waste 1-ethyl-3-(3-(dimethylamino)propyl)urea (EDU) are shown. The reactive molecule sites, recognition motifs (for example, thymine) and complete molecular structures are colour-coded as follows: monomer acid (blue), thymine (red), adenine (green), oligomer anhydride (orange), fuel (purple) and waste (black). The pictograms for thymine oligomers are coloured red and the DNA template is coloured green. b, The chemical reaction system converts a chemical fuel (EDC) into waste (EDU) while building up oligomers that are part of a transient dynamic combinatorial library.

Template-based copying in chemically fuelled dynamic combinatorial libraries,Nature Chemistry (open access)

Astrobiology