520-million-year-old worm Fossil Solves Mystery Of How Modern Insects, Spiders and Crabs Evolved

A new study led by researchers at Durham University have uncovered an incredibly rare and detailed fossil, named Youti yuanshi, that gives a peek inside one of the earliest ancestors of modern insects, spiders, crabs and centipedes.

This fossil dates back over 520 million years to the Cambrian period, when the major animal groups we know today were first evolving.

This fossil belongs to a group called the euarthropods, which includes modern insects, spiders and crabs. What makes this fossil so special is that the tiny larva, no bigger than a poppy seed, has its internal organs preserved in exceptional quality.

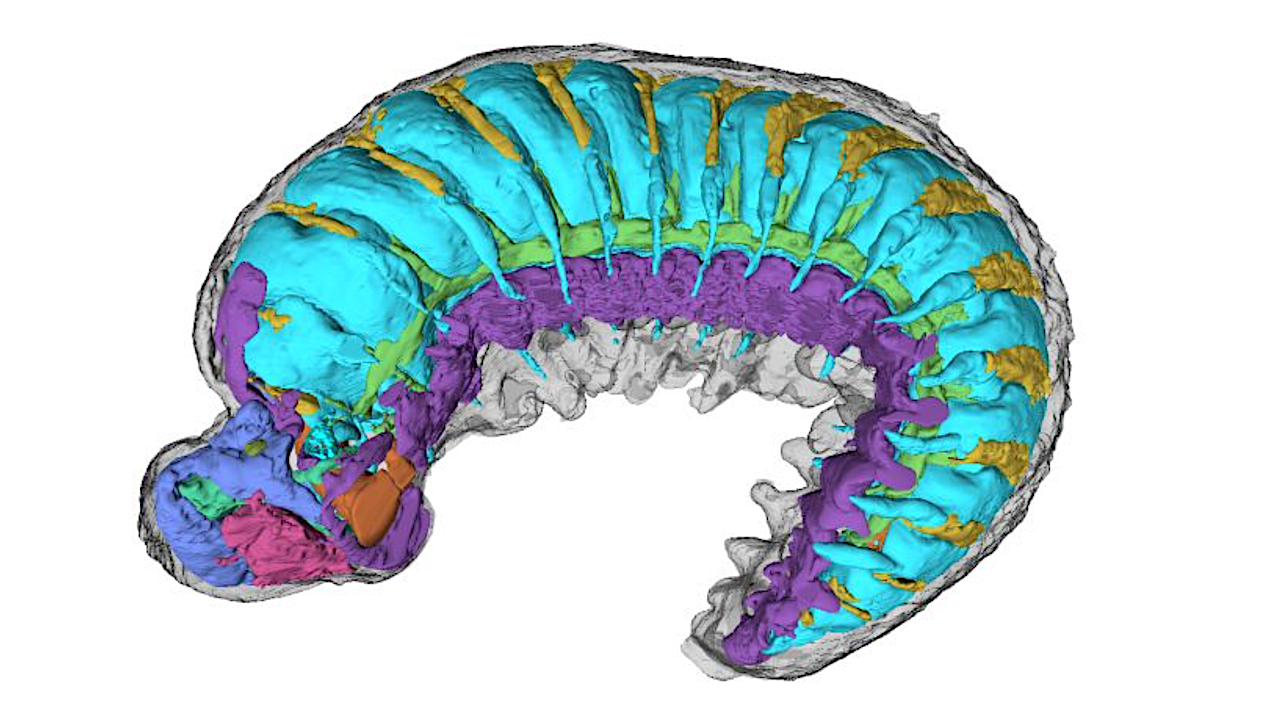

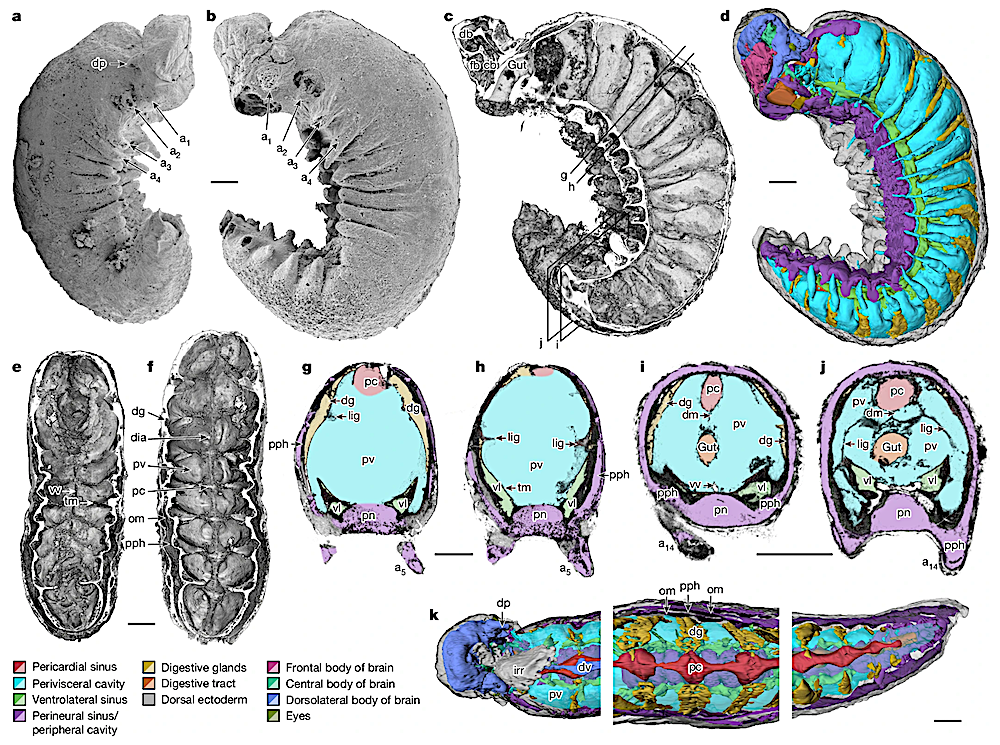

Using advanced scanning techniques of synchrotron X-ray tomography at Diamond Light Source, the UK’s national synchrotron science facility, researchers generated 3D images of miniature brain regions, digestive glands, a primitive circulatory system and even traces of the nerves supplying the larva’s simple legs and eyes.

This fossil allows researchers to look under the skin of one of the first arthropod ancestors. The level of complexity anatomy shows these early arthropod-relatives were much more advanced than the researchers thought.

Lead researcher, Dr Martin Smith of Durham University said: “When I used to daydream about the one fossil I’d most like to discover, I’d always be thinking of an arthropod larva, because developmental data are just so central to understanding their evolution.

“But larvae are so tiny and fragile, the chances of finding one fossilised are practically zero – or so I thought! I already knew that this simple worm-like fossil was something special, but when I saw the amazing structures preserved under its skin, my jaw just dropped – how could these intricate features have avoided decay and still be here to see half a billion years later?”

Study co-author, Dr Katherine Dobson of the University of Strathclyde said: “It’s always interesting to see what’s inside a sample using 3D imaging, but in this incredible tiny larva, natural fossilisation has achieved almost perfect preservation.”

Studying this ancient larva provides key clues about the evolutionary steps required for simple worm-like creatures to transform into the sophisticated arthropod body plan with specialised limbs, eyes and brains.

For example, the fossil reveals an ancestral ‘protocerebrum’ brain region that would later form the nub of the segmented and specialised arthropod head with its various appendages like antennae, mouthparts and eyes.

This complex head allowed arthropods to take on a wide range of lifestyles and allowed the researchers to become the dominant organisms in the Cambrian oceans.

Details like these also help trace how modern arthropods gained their incredible anatomical complexity and diversity and came to be the most abundant group of animals today.

The researchers point out that fossil fills an important gap in our understanding of how the arthropod body plan originated and became so successful during the Cambrian Explosion of life.

This remarkable specimen is housed at Yunnan University in China, where it was originally discovered.

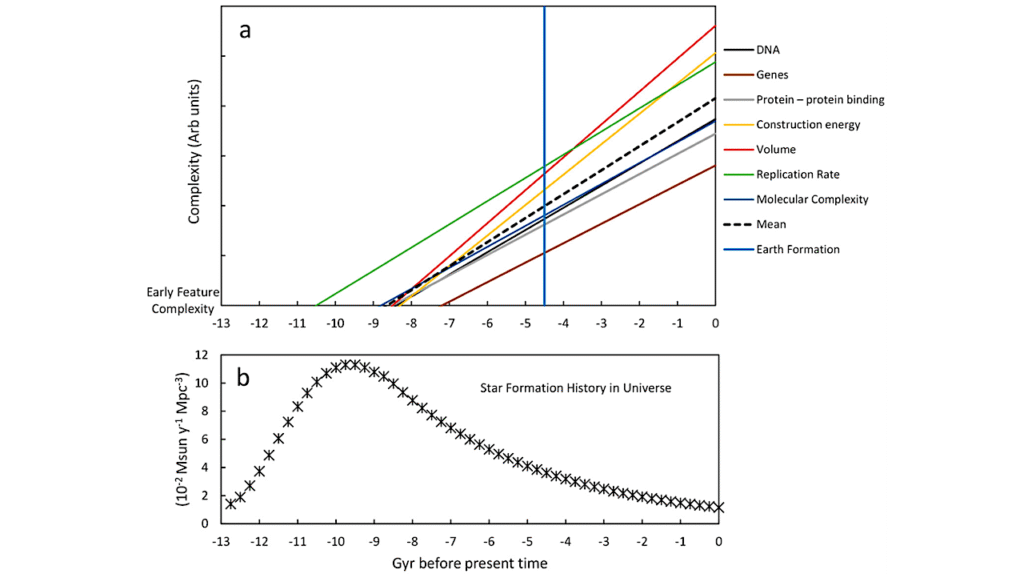

Organ system disposition in sagittal view. Dotted lines denote location of sections shown in e,f. b, Organ system disposition in transverse view. c,d, Head, from lateral perspective (c) and as medial transverse section (d). e,f, Transverse sections through trunk at location of digestive glands (e) and transverse membranes (f). g–j, Coronal sections through head, from ventral (g) to dorsal (j) planes. Colour scheme as in Fig. 1. — Nature

IMAGE

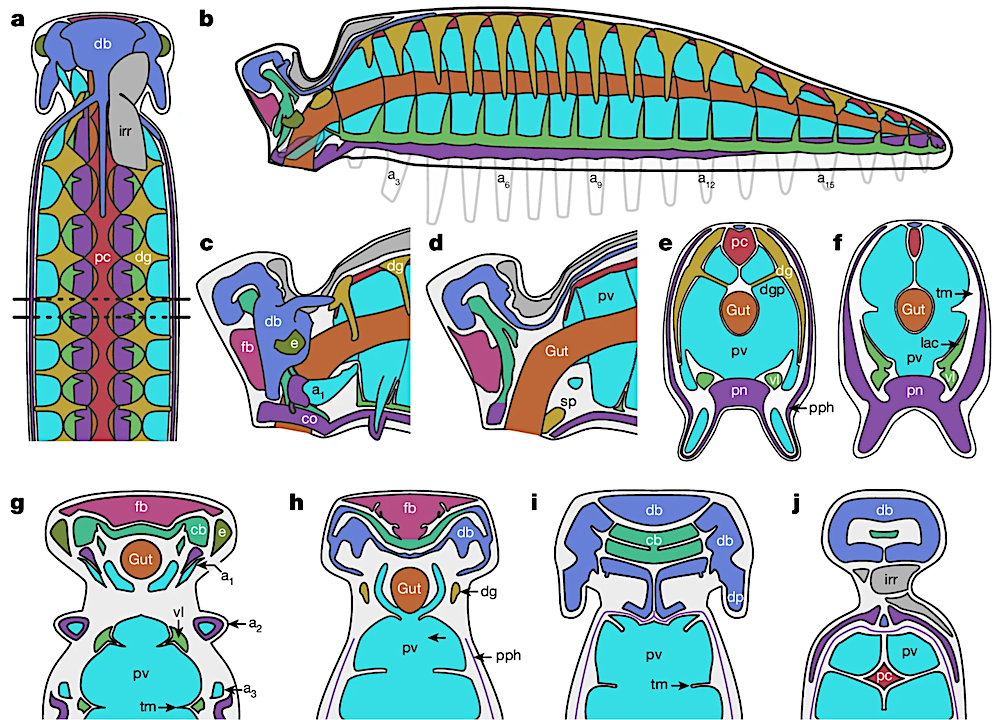

YKLP 12387. a, External scanning electron microscopy, right side. Damage to posterior epidermis exposes lining of perivisceral cavity, demonstrating blind gut. b, External scanning electron microscopy, left side. c,g–j, Median virtual dissection from X-ray computed tomography (XCT) data (c), showing location of transverse slices intersecting digestive glands (g,i) and transverse membrane (h,j). d, Semi-manual segmentation of internal chambers from XCT data, viewed from the left side. Dorsolateral aspects of the peripheral cavity are omitted for clarity. e,f, Virtual dissection parallel to coronal plane, looking ventrally (e) and dorsally (f), showing digestive glands, pericardial sinus, transverse membranes within perivisceral cavity, and oblique membranes within peripheral cavity. g–j, XCT sections at positions indicated in c at position of digestive glands (g,i) and at position of ventrolateral lacunae and transverse membrane (h,j). g,h, Sections close to the anterior trunk, reflecting segments at late developmental stage. i,j, Sections close to the posterior trunk, showing superior preservation of internal tissue. k, Segmentation of internal chambers from XCT data, viewed from the dorsal perspective at anterior, middle and posterior trunk. Aspects of peripheral cavity are omitted for clarity. a, appendage; cb, central body of brain; db, dorsolateral body of brain; dia, diagenetic grain; dg, digestive gland; dm, dorsal membrane; dp, dorsal projection; dv, dorsal vessel; fb, frontal body of brain; irr, irregular chamber; lig, ligament; om, oblique membrane; pc, pericardial sinus; pph, peripheral cavity; pn, perineural sinus; pv, perivisceral cavity; tm, transverse membrane; vl, ventrolateral sinus; vv, ventral vessel. Scale bars, 200 μm. — Nature

Organ systems of a Cambrian euarthropod larva, Nature (open access)

Astrobiology