In The Search For Alien Life, Purple May Be The New Green

In the search for life across the cosmos, the familiar green hue we most associate with life on Earth may not be the best indicator. An Earth-like planet orbiting another star might look very different, potentially covered by bacteria that use invisible infrared radiation to power photosynthesis.

Many such bacteria on Earth contain purple pigments, and purple worlds on which they are dominant would produce a distinctive “light fingerprint” detectable by next-generation ground- and space-based telescopes, Cornell University scientists report in new research.

“Purple bacteria can thrive under a wide range of conditions, making it one of the primary contenders for life that could dominate a variety of worlds,” said Lígia Fonseca Coelho, a postdoctoral associate at the Carl Sagan Institute (CSI) and first author of “Purple is the New Green: Biopigments and Spectra of Earth-like Purple Worlds.”

“We need to create a database for signs of life to make sure our telescopes don’t miss life if it happens not to look exactly like what we encounter around us every day,” added co-author Lisa Kaltenegger, CSI director and associate professor of astronomy.

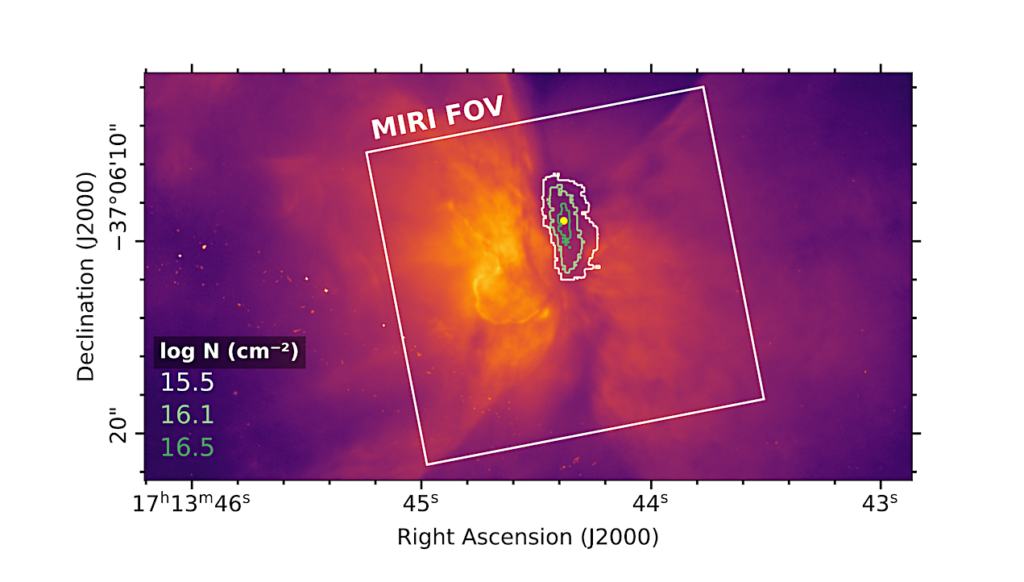

Filters showing the measured purple non-sulfur bacteria (E01, E02, E11, E18, E23, E26, E33, E45, BV, and RV), purple sulfur bacteria (E03, E05, E06, E07, E10, E13, E28, E35, E41, E50, E51, E53), and purple cyanobacteria (Glo). For details on the biota see Table S1., Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society

Using life on Earth as a guide, the multidisciplinary team of scientists are cataloging the colors and chemical signatures that a diverse range of organisms and minerals would present in an exoplanet’s reflected light.

What are collectively referred to as purple bacteria actually have a range of colors including yellow, orange, brown and red, due to pigments related to those that make tomatoes red and carrots orange. They thrive on low-energy red or infrared light using simpler photosynthesis systems utilizing forms of chlorophyll that absorb the infrared and don’t make oxygen. They are likely to have been prevalent on early Earth before the advent of plant-type photosynthesis, the researchers said, and could be particularly well-suited to planets that circle cooler red dwarf stars – the most common type in our galaxy.

“They already thrive here in certain niches,” Coelho said. “Just imagine if they were not competing with green plants, algae and bacteria: A red sun could give them the most favorable conditions for photosynthesis.”

After measuring the purple bacteria’s biopigments and light fingerprints, the researchers created models of Earth-like planets with varying conditions and cloud cover. Across a range of simulated environments, Coelho said, both wet and dry purple bacteria produced intensely colored biosignatures.

“If purple bacteria are thriving on the surface of a frozen Earth, an ocean world, a snowball Earth or a modern Earth orbiting a cooler star,” Coelho said, “we now have the tools to search for them.”

Detecting a “pale purple dot” in another solar system would trigger intensive observations of the planet to try to rule out other color sources, such as colorful minerals, which CSI also is cataloging. Kaltenegger, author of the forthcoming book, “Alien Earths: The New Science of Planet Hunting in the Cosmos,” said detecting life is so difficult with current technology that if even single-celled organisms are found in one place, it would suggest that life must be widespread in the cosmos. That would revolutionize our thinking about the age-old question: Are we alone in the universe?

“We are just opening our eyes to these fascinating worlds around us,” Kaltenegger said. “Purple bacteria can survive and thrive under such a variety of conditions that it is easy to imagine that on many different worlds, purple may just be the new green.”

The research was supported by a Fulbright Schuman grant, the Brinson Foundation and the National Science Foundation.

Purple is the new green: biopigments and spectra of Earth-like purple worlds, Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (open access)

Astrobiology