Lunar Spacecraft Exhaust Could Obscure Clues To Origins Of Life

Over half of the exhaust methane from lunar spacecraft could end up contaminating areas of

the moon that might otherwise yield clues about the origins of earthly life, according to

a recent study. The pollution could unfold rapidly regardless of a spacecraft’s touchdown

site; even for a landing at the South Pole, methane molecules may “hop” across the lunar

surface to the North Pole in under two lunar days.

As interest in lunar exploration resurges among governments, private companies and NGOs,

the study authors wrote, it becomes crucial to understand how exploration may impact

research opportunities. This knowledge can help inform the creation of planetary

protection strategies for the lunar environment, as well as lunar missions designed to

minimize impact on that environment — and the clues about our past it may contain.

The study appears in Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets, AGU’s journal for original

research in planetary science.

“We are trying to protect science and our investment in space,” said Silvio Sinibaldi, the

planetary protection officer at the European Space Agency and senior author on the study.

The moon is a natural laboratory ripe for new discoveries, he said — but, paradoxically,

“our activity can actually hinder scientific exploration.”

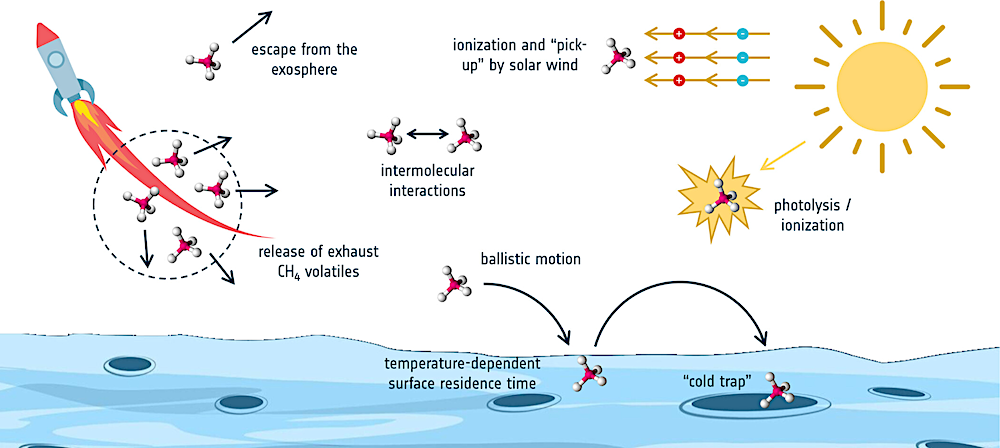

Schematic representation of the physical processes and pathways modeled for exhaust

CH4 molecules. Adapted from Prem et al. (2020). — Journal of Geophysical Research:

Planets

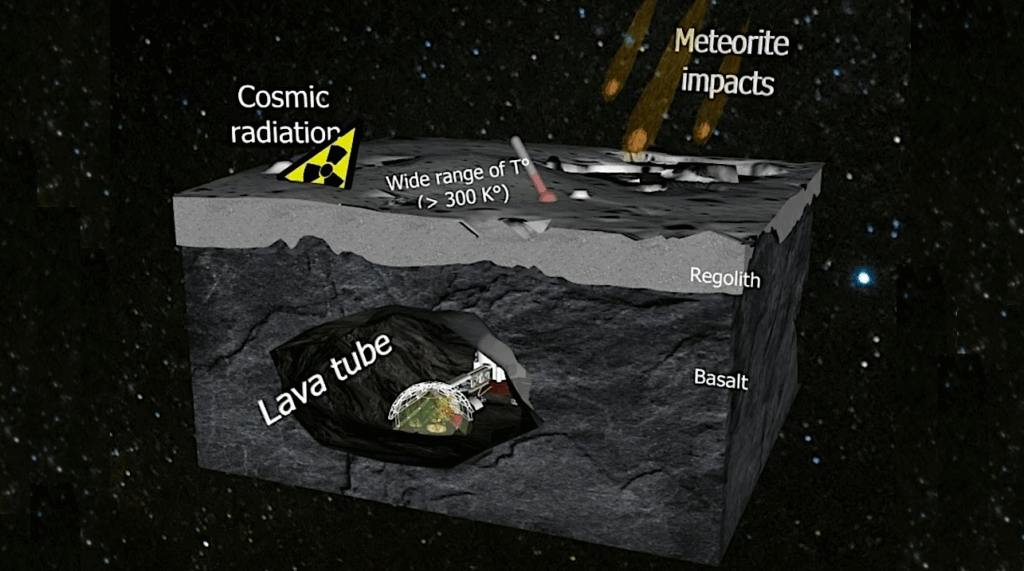

At the moon’s poles, craters cloaked in perpetual darkness (called permanently shadowed

regions) hold ice which might contain materials delivered to the moon and Earth via comets

and asteroids billions of years ago. Scientists hope those materials might include

“prebiotic organic molecules” — key ingredients that, under the right conditions, may have

combined to form the original building blocks of life, such as DNA. Finding those

molecules in their original form could allow researchers to study how they gave rise to

life on Earth.

“We know we have organic molecules in the solar system — in asteroids, for example,”

Sinibaldi said. “But how they came to perform specific functions like they do in

biological matter is a gap we need to fill.”

Earth’s dynamic, ever-changing surface likely erased any trace of what those original

molecules looked like long ago. The moon’s surface, parts of which have remained

relatively unaltered for billions of years, may preserve a better record — especially in

the permanently shadowed regions, where molecules tend to accumulate due to cold

temperatures that slow their movement. Unfortunately, that may also include molecules

released by lunar spacecraft, potentially obscuring pristine evidence of life-originating

materials.

A molecular mad dash

Sinibaldi and Francisca Paiva, a physicist at Instituto Superior Técnico and lead author

of the study, built a computer model to simulate how that contamination might play out,

using the European Space Agency’s Argonaut mission as a case study. The simulations

focused on how methane, the main organic compound released during combustion of Argonaut

propellants, might spread across the lunar surface during a landing at the moon’s South

Pole. While previous studies had investigated how water molecules might move on the moon,

none had done so for organic molecules like methane. The new model also accounted for how

factors like solar wind and UV radiation would impact the methane’s behavior.

“We were trying to model thousands of molecules and how they move, how they collide with

one another, and how they interact with the surface,” said Paiva, who was a master’s

student at KU Leuven and an intern at the European Space Agency during the research. “It

required a lot of computational power. We had to run each simulation for days or weeks.”

The model showed exhaust methane reaching the North Pole in under two lunar days. Within

seven lunar days (almost 7 months on Earth), more than half of the total exhaust methane

had been “cold trapped” at the frigid poles — 42% at the South Pole and 12% at the North.

“The timeframe was the biggest surprise,” Sinibaldi said. “In a week, you could have

distribution of molecules from the South to the North Pole.”

That’s partly because the moon has almost no atmosphere of other molecules to bump into.

Impeded only by gravity, methane molecules on the moon bound freely across the landscape

like bouncy balls across an empty room, energized by sunlight and slowed by cold.

“Their trajectories are basically ballistic,” Paiva said. “They just hop around from one

point to another.” That’s concerning, she explained, because it means there may be no

foolproof landing sites anywhere. “We showed that molecules can travel across the whole

moon. In the end, wherever you land, you will have contamination everywhere.”

That doesn’t mean there’s nothing to be done to minimize contamination. Colder landing

sites, Paiva noted, might still corral exhaust molecules better than warmer ones. There

might also be ways around the contamination: Sinibaldi wants to study whether exhaust

molecules might simply settle on the icy surfaces of PSRs, leaving material underneath

unscathed for research.

Above all, the duo said, the results need confirmation from both additional simulations

and real-life measurements on the moon. “I want to bring this discussion to mission teams,

because, at the end of the day, it’s not theoretical — it’s a reality that we’re going to

go there,” Sinibaldi said. “We will miss an opportunity if we don’t have instruments on

board to validate those models.”

Paiva hopes to study whether molecules other than methane, including those in spacecraft

hardware like paint and rubber, might also pose risks to research.

“We have laws regulating contamination of Earth environments like Antarctica and national

parks,” she said. “I think the moon is an environment as valuable as those.”

Notes for journalists: This study is published in Journal of Geophysical Research:

Planets, an AGU journal. View and download a pdf of the study here. Neither this press

release nor the study is under embargo.

Paper title: “Can Spacecraft-Borne Contamination Compromise Our Understanding of Lunar Ice Chemistry?”

Authors: Francisca S. Paiva, Instituto Superior Técnico, Lisbon, Portugal

Silvio Sinibaldi, European Space Agency, Noordwijk, The Netherlands; The Open University,

Milton Keynes, United Kingdom

AGU (www.agu.org) is a global community supporting more than half a million professionals

and advocates in Earth and space sciences. Through broad and inclusive partnerships, AGU

aims to advance discovery and solution science that accelerate knowledge and create

solutions that are ethical, unbiased and respectful of communities and their values. Our

programs include serving as a scholarly publisher, convening virtual and in-person events

and providing career support. We live our values in everything we do, such as our net zero

energy renovated building in Washington, D.C. and our Ethics and Equity Center, which

fosters a diverse and inclusive geoscience community to ensure responsible conduct.

Astrobiology