Puzzle About Nitrogen Solved Thanks to Cometary Analogues

Comets and asteroids are objects in our solar system that have not developed much since the planets were formed. As a result, they are in a sense the archives of the solar system, and determining their composition could also contribute to a better understanding of the formation of the planets.

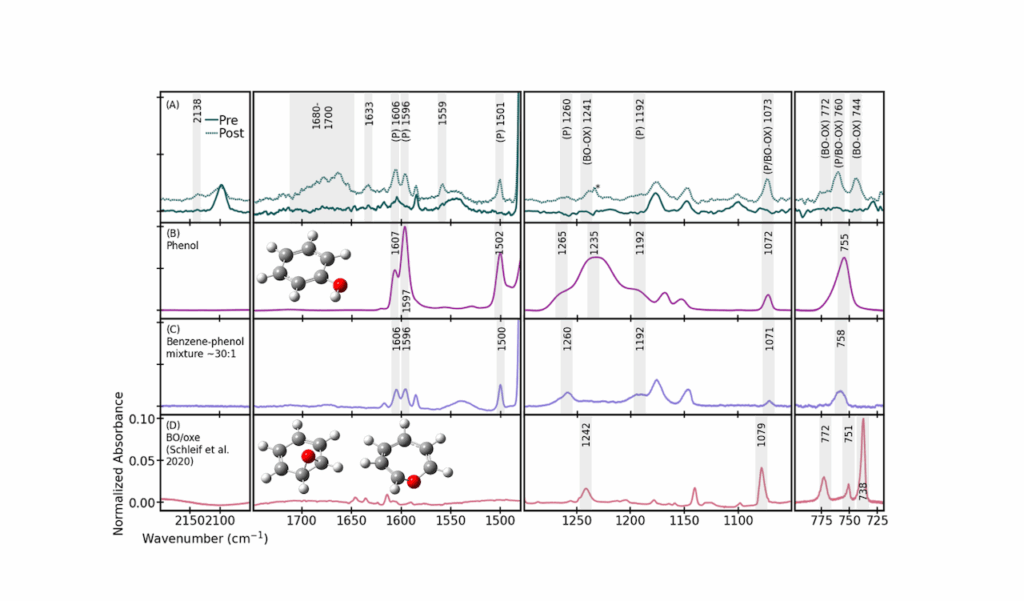

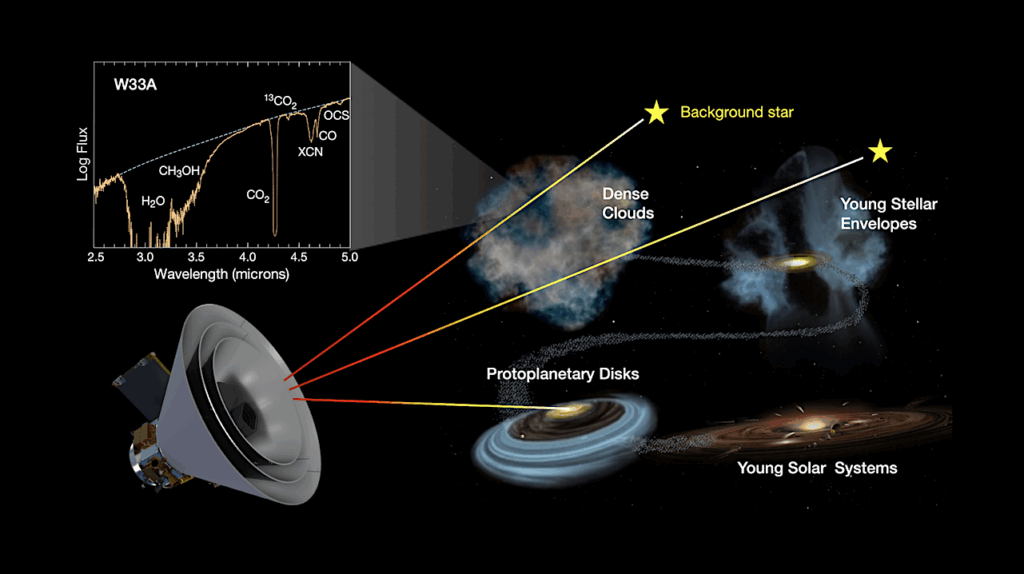

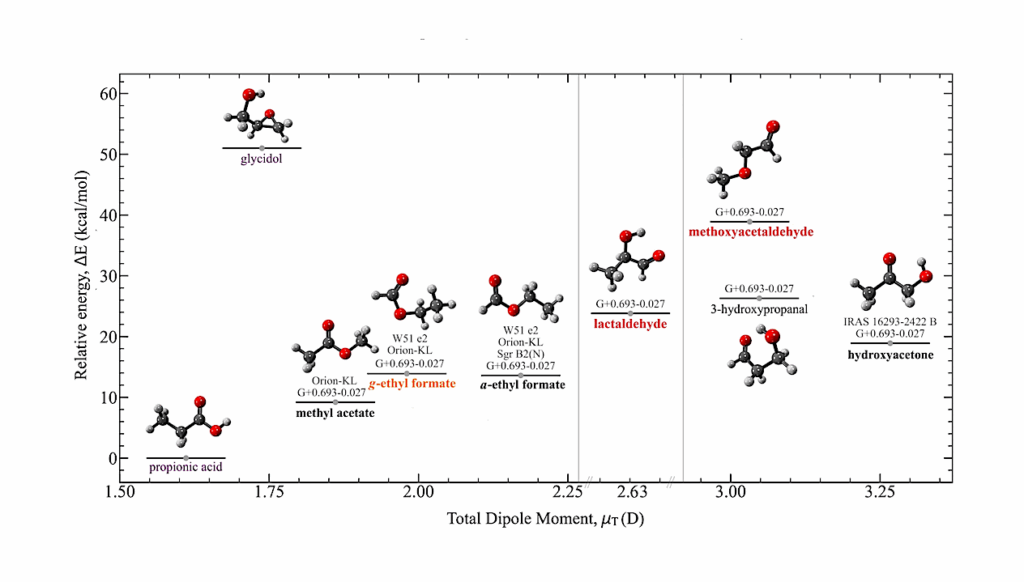

One way to determine the composition of asteroids and comets is to study the sunlight reflected by them, since the materials on their surface absorb sunlight at certain wavelengths. We talk about a comet’s spectrum, which has certain absorption features. VIRTIS (Visible, InfraRed and Thermal Imaging Spectrometer) on board the European Space Agency’s (ESA) Rosetta space probe mapped the surface of comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko, known as Chury for short, from August 2014 to May 2015. The data gathered by VIRTIS showed that the cometary surface is uniform almost everywhere in terms of composition: The surface is very dark and slightly red in color, because of a mixture of complex, carbonaceous compounds and opaque minerals. However, the exact nature of the compounds responsible for the measured absorption features on Chury has been difficult to establish until now.

Cometary Analogue Provided the Solution to the Puzzle

To identify which compounds are responsible for the absorption features, researchers led by Olivier Poch from the Institute of Planetology and Astrophysics at the Université de Grenoble Alpes carried out laboratory experiments in which they created cometary analogues and simulated conditions similar to those in space. Poch had developed the method together with researchers from Bern when he was still working at the University of Bern Physics Institute. The researchers tested various potential compounds on the cometary analogues and measured their spectra, just as the VIRTIS instrument on board Rosetta had done with Chury’s surface. The experiments showed that ammonium salts explain specific features in the spectrum of Chury.

Antoine Pommerol from the University of Bern Physics Institute is one of the co-authors of the study, which is now published in the Science journal. He explains: “While Olivier Poch was working at the University of Bern, we jointly developed methods and procedures to create replicas of the surfaces of cometary nuclei.” The surfaces were altered by sublimating the ice on them under simulated space conditions. “These realistic laboratory simulations allow us to compare laboratory results and data recorded by the instruments on Rosetta or other comet missions. The new study builds on these methods to explain the strongest spectral feature observed by the VIRTIS spectrometer with Chury,” Pommerol continues. Nicolas Thomas, Director of the University of Bern Physics Institute and also co-author of the study, says: “Our laboratory in Bern offers the ideal opportunities to test ideas and theories with experiments that have been formulated on the basis of data gathered by instruments on space missions. This ensures that the interpretations of the data are really plausible.”

Vital Building Block “Hides” in Ammonium Salts

The results are identical to those from the Bern mass spectrometer ROSINA, which had also gathered data on Chury on board Rosetta. A study published in Nature Astronomy in February under the leadership of astrophysicist Kathrin Altwegg was the first to detect nitrogen, one of the basic building blocks of life, in the nebulous covering of comets. It had “hidden” itself in the nebulous covering of Chury in the form of ammonium salts, the occurrence of which could not be measured until now.

Although the exact amount of salt is still difficult to estimate from the available data, it is likely that these ammonium salts contain most of the nitrogen present in the Chury comet. According to the researchers, the results also contribute to a better understanding of the evolution of nitrogen in interstellar space and its role in prebiotic chemistry.

Reference:

“Ammonium Salts Are a Reservoir of Nitrogen on a Cometary Nucleus and Possibly on Some Asteroids,” O. Poch et al., 2020 Mar. 12, Science [https://science.sciencemag.org, http://dx.doi.org/10.1126/science.aaw7462].

Astrobiology, Astrochemistry