Fossilized Tracks Suggest Multicellular Life Far Older Than Previously Thought

Newly discovered fossilized tracks suggest multicellular life could be 1.5 billion years older than previously thought, according to a new study by an international team of researchers including scientists at the University of Alberta.

“The preservation of fossilized tracks, or trace fossils, suggests that multicellular organisms that could move around to reach food resources may already have existed 2.1 billion years ago, more than 1.5 billion years older than previously thought,” explained Kurt Konhauser, professor in the University of Alberta’s Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences and co-author on the study.

Ancient fossilized tracks suggest multicellular organisms originated 2.1 billion years ago.

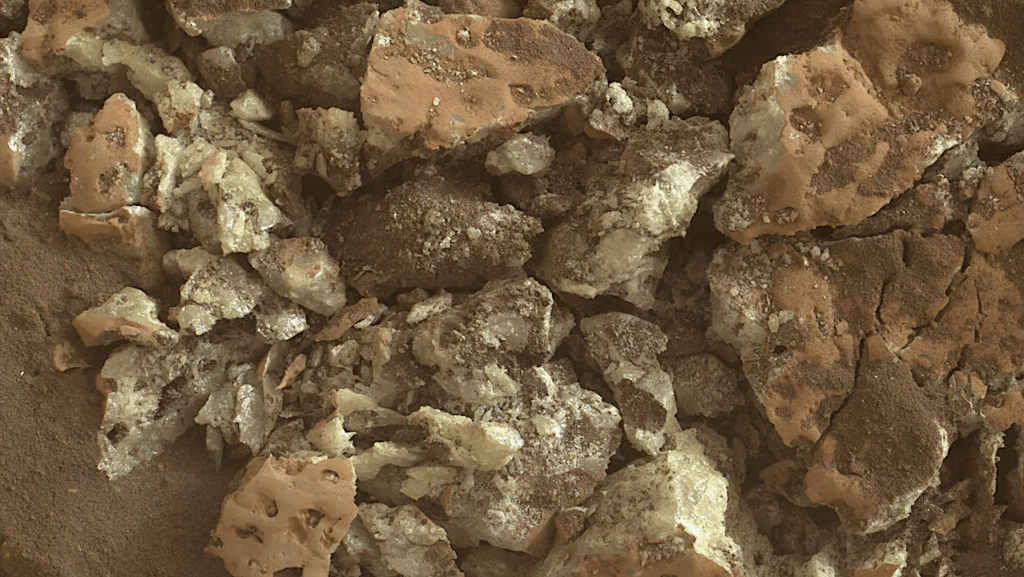

The sample that contains the fossilized tracks of early multicellular life. Image courtesy of Abder El Albani.

The fossils, found in the Francevillian Series Formation, located in Gabon, Africa, are likely the result of ancient mucus trails, left by multicellular life such as modern amoeboid cells in the search for food. The samples range from 6 millimeters across and 170 millimeters in length through the sediment layers. But despite their small size, the paper on this discovery has sparked international controversy.

“The question arising from this research then is why do we go 1.5 billion years before we see similar features in the rock record?” asked Konhauser. “We don’t see anything like this again until 585 million years ago.”

Some speculate that this early emergence of complex life went extinct due to some environmental factor. Others suggest that similar fossilized traces may have existed but were not preserved, or simply gone unnoticed elsewhere.

“The broader community is right to be skeptical about the interpretation,” said Konhauser. “However, one of the current paradigms relating to the evolution of multicellular organisms is oxygen availability, and 2.1 billion years ago there was no shortage of oxygen in shallow marine waters.”

Future research will examine similar well-oxygenated, shallow-marine environments that are between 2.1 billion and 500 million years old.

This research was conducted in collaboration with Abder El Albani of the University of Poitiers in Poitiers, France. The paper, “Organism motility in an oxygenated shallow-marine environment 2.1 billion years ago,” was published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA (doi: 10.1073/pnas.1815721116).