No Limit to Life in Deep Sediment of Ocean's Deadest Region

“Who in his wildest dreams could have imagined that, beneath the crust of our Earth, there could exist a real ocean…a sea that has given shelter to species unknown?”

So wrote Jules Verne almost 150 years ago in A Journey to the Center of the Earth.

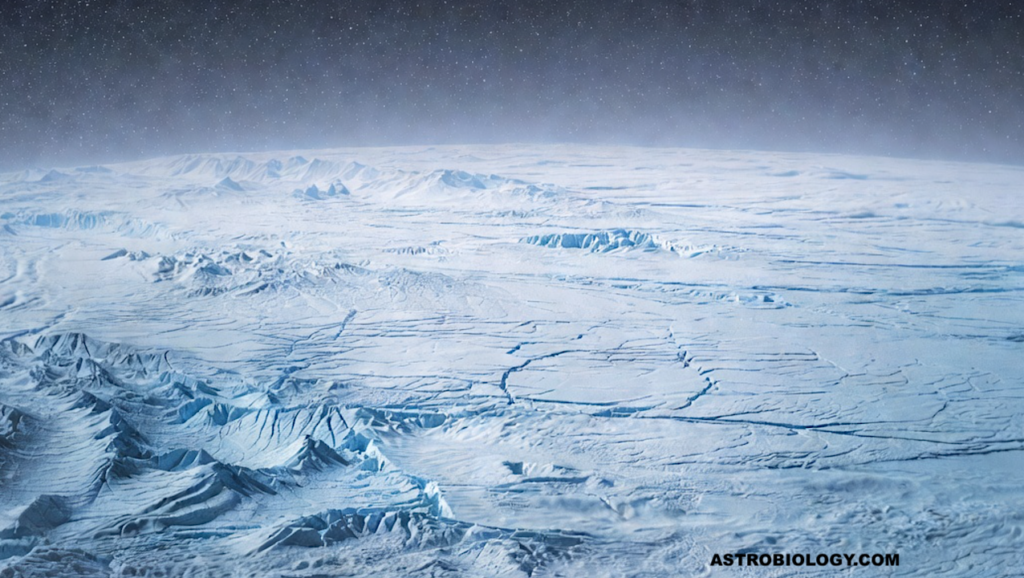

He was correct: Ocean deeps are anything but dead.

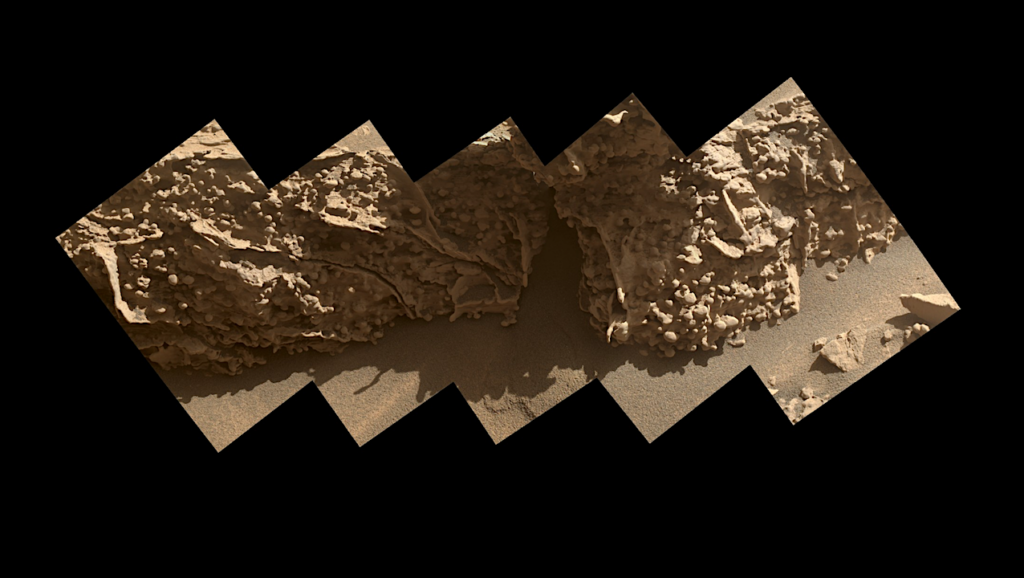

Now, scientists have found oxygen and oxygen-breathing microbes all the way through the sediment from the seafloor to the igneous basement at seven sites in the South Pacific gyre, considered the “deadest” location in the ocean.

Findings contrast with previous studies

Their findings contrast with previous discoveries that oxygen was absent from all but the top few millimeters to decimeters of sediment in biologically productive regions of the ocean.

The results are published today in a paper in the journal Nature Geoscience.

“Our objective was to understand the microbial community and microbial habitability of sediment in the deadest part of the ocean,” said scientist Steven D’Hondt of the University of Rhode Island Graduate School of Oceanography, lead author of the paper.

“Our results overturn a 60-year-old conclusion that the depth limit to life is in the sediment just meters below the seafloor in such regions.

“We found that there is no limit to life in this sediment. Oxygen and aerobic microbes hang in there all the way to the igneous basement, to at least 75 meters below the seafloor.”

Under the seafloor, life all the way down

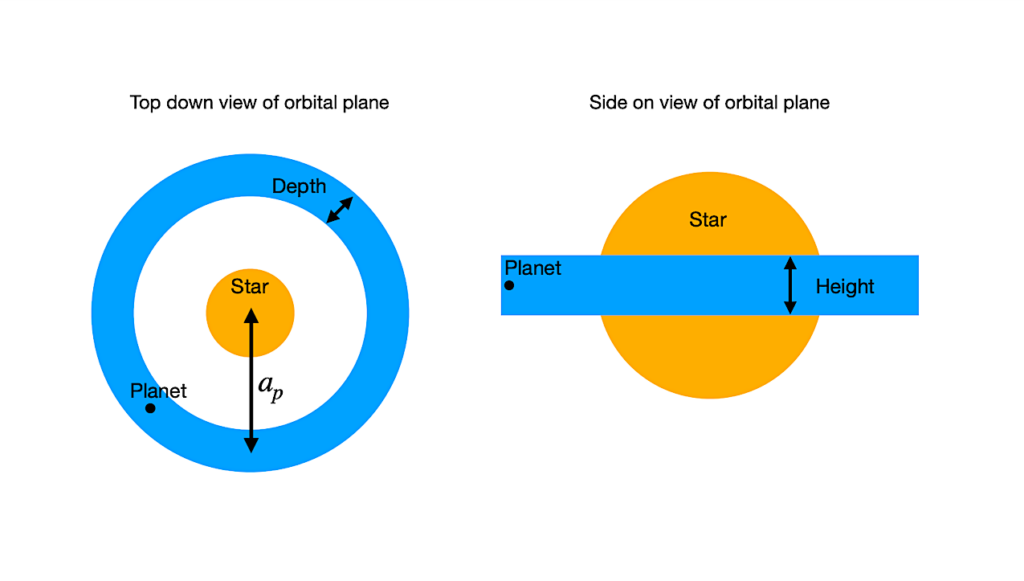

Based on the researchers’ predictive model and core samples they collected in 2010 from the research drillship JOIDES Resolution, they believe that oxygen and aerobic microbes occur throughout the sediment in up to 37 percent of the world’s oceans and 44 percent of the Pacific Ocean.

They found that the best indicators of oxygen penetration to the igneous basement are a low sedimentation accumulation rate and a relatively thin sediment layer.

Sediment accumulates at just a few decimeters to meters per million years in the regions where the core samples were collected.

In the remaining 63 percent of the ocean, most of the sediment beneath the seafloor is expected to lack dissolved oxygen and to contain anaerobic communities.

While the researchers found evidence of life throughout the sediment, they did not detect a great deal of it.

Life in the slow lane

The team found extremely slow rates of respiration and approximately 1,000 cells per cubic centimeter of subseafloor sediment in the South Pacific gyre–rates and quantities that had been nearly undetectable.

“It’s really hard to find life when it’s not very active and is in extremely low concentrations,” said D’Hondt.

According to D’Hondt and co-author Fumio Inagaki of the Japan Agency for Marine-Earth Science and Technology, the discovery of oxygen throughout the sediment may have significant implications for Earth’s chemical evolution.

The oxidized sediment is likely carried into the mantle at subduction zones, regions of the seafloor where tectonic plates collide, forcing one plate beneath the other.

“Subduction of these big regions where oxygen penetrates through the sediment and into the igneous basement introduces oxidized minerals to the mantle, which may affect the chemistry of the upper mantle and the long-term evolution of Earth’s surface oxidation,” D’Hondt said.

Holistic approach to study of subseafloor biosphere

The principal research funders were the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF) and Japan’s Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology.

“We take a holistic approach to the subseafloor biosphere,” said Rick Murray, co-author of the paper. Murray is on leave from Boston University, currently serving as director of the NSF Division of Ocean Sciences.

“Our team includes microbiologists, geochemists, sedimentologists, physical properties specialists and others–a hallmark of interdisciplinary research.”

The research involved 35 scientists from 12 countries.

The project is part of the NSF-funded Center for Dark Energy Biosphere Investigations (C-DEBI), which explores life beneath the seafloor.

The research is also part of the Deep Carbon Observatory, a decade-long international science initiative to investigate the 90 percent of Earth’s carbon located deep inside the planet.

The Nature Geoscience paper is available online.