NASA Researchers Discover Ancient Microbes in Antarctic Lake

In one of the most remote lakes of Antarctica, nearly 65 feet beneath the icy surface, scientists from NASA, the Desert Research Institute (DRI) in Reno, Nev., the University of Illinois at Chicago, and nine other institutions, have uncovered a community of bacteria.

This discovery of life existing in one of Earth’s darkest, saltiest and coldest habitats is significant because it helps increase our limited knowledge of how life can sustain itself in these extreme environments on our own planet and beyond.

Lake Vida, the largest of several unique lakes found in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, contains no oxygen, is mostly frozen and possesses the highest nitrous oxide levels of any natural water body on Earth. A briny liquid, which is approximately six times saltier than seawater, percolates throughout the icy environment where the average temperature is minus 8 degrees Fahrenheit. The international team of scientists published their findings online Nov. 26, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences Early Edition.

“This study provides a window into one of the most unique ecosystems on Earth,” said Alison Murray, a molecular microbial ecologist and polar researcher at the DRI and the report’s lead author. “Our knowledge of geochemical and microbial processes in lightless icy environments, especially at subzero temperatures, has been mostly unknown up until now. This work expands our understanding of the types of life that can survive in these isolated, cryoecosystems and how different strategies may be used to exist in such challenging environments.”

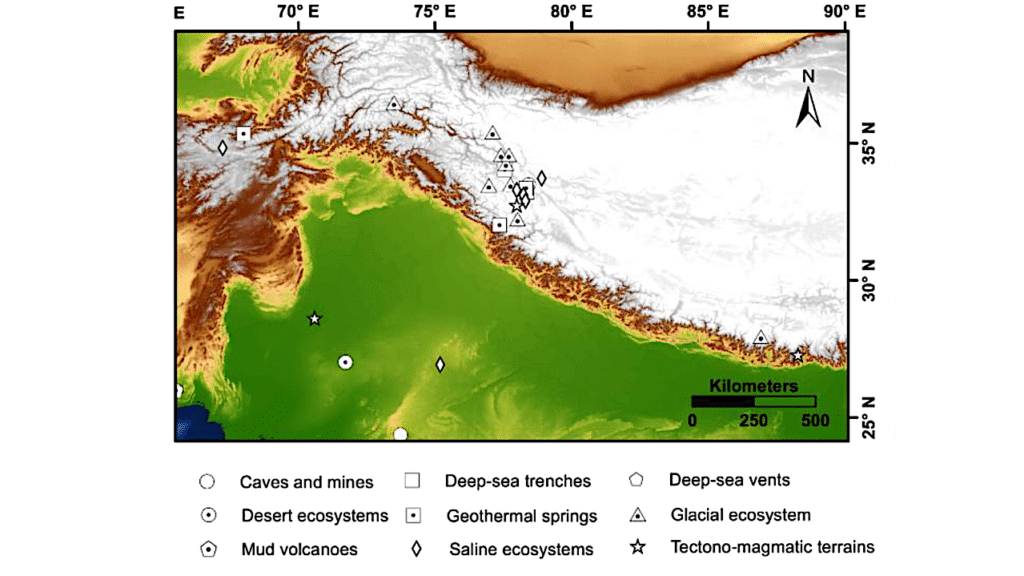

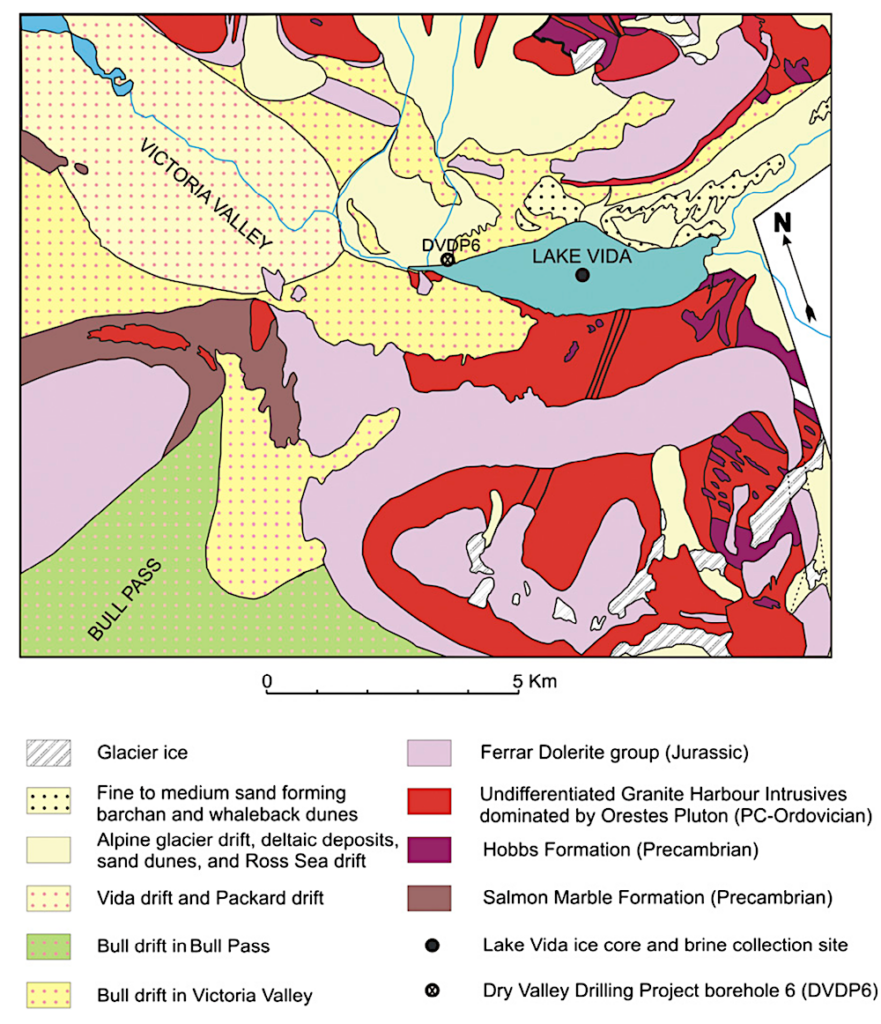

(A) Map of Antarctica showing the location of the McMurdo Dry Valleys. (B) National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) Earth Observatory, Landsat 7 satellite image of a part of McMurdo Dry Valleys showing the location of Lake Vida (Vi) and Lake Vanda (Va), Fryxell (F), Hoare (H), Bonney (B), and Blood Falls (BF). The filled circle at the center of Lake Vida indicates the location of the borehole. The white rectangle indicates the area covered by the geologic map (Fig. S3). The location of sampling in 2005 and 2010 is indicated by a dot.

Despite the very cold, dark and isolated nature of the habitat, the report finds the brine harbors a surprisingly diverse and abundant variety of bacteria that survive without a current source of energy from the sun. Previous studies of Lake Vida dating back to 1996 indicate the brine and its inhabitants have been isolated from outside influences for more than 3,000 years.

“This system is probably the best analog we have for possible ecosystems in the subsurface waters of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Jupiter’s moon Europa,” said Chris McKay, a senior scientist and co-author of the paper at NASA’s Ames Research Center, Moffett Field, Calif.

Murray and her co-authors and collaborators, including Peter Doran, the project’s principal investigator at the University of Illinois at Chicago, developed stringent protocols and specialized equipment for their 2005 and 2010 field campaigns to sample from the lake brine while avoiding contaminating the pristine ecosystem.

Lake Vida, one of the most remote lakes in Antarctica. Image credit: NASA Ames/Chris McKay

“The microbial ecosystem discovered at Lake Vida expands our knowledge of environmental limits for life and helps define new niches of habitability,” said Adrian Ponce, co-author from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., who enumerated viable bacterial spore populations extracted from Lake Vida.

To sample unique environments such as this, researchers must work under secure, sterile tents on the lake’s surface. The tents kept the site and equipment clean as researchers drilled ice cores, collected samples of the salty brine residing in the lake ice and assessed the chemical qualities of the water and its potential for harboring and sustaining life.

Geochemical analyses suggest chemical reactions between the brine and the underlying iron-rich sediments generate nitrous oxide and molecular hydrogen. The latter, in part, may provide the energy needed to support the brine’s diverse microbial life.

Geological description of Lake Vida basin and Victoria Valley. (A) View of the southern and southwestern shores of Lake Vida showing two large Ferrar dolerite sills (darker layers) cross cutting granite of the Orestes Pluton. The lake is 349 m above sea level; the marked summit is ∼1,450 m high. The arrow points to the dark dolerite-dominated Bull Drift. (B) View of the southern shore of Lake Vida showing two large Ferrar dolerite sills (darker layers) crosscutting granite (lighter in color). The marked summit is Mt. Cerberus (1,766 m). The arrow points to the camp site in the center of the lake. (C) View toward the northeastern shore of Lake Vida. The darker layers are made of Ferrar dolerite the lighter layers are granite. The marked summit is above 1,200 m. The white arrow points to aeolian sand deposits dominated by Fe.Mg silicates and Ca.Fe.Mg silicates (pyroxenes). The black arrow points to camp in the center of Lake Vida. The rocks at the forefront are granite ventifacts.

Additional research is under way to analyze the abiotic, chemical interactions between the Lake Vida brine and its sediment, in addition to investigating the microbial community by using different genome sequencing approaches. The results could help explain the potential for life in other salty, cryogenic environments beyond Earth, such as purported subsurface aquifers on Mars.

This study was partially funded by the NASA Astrobiology Program in collaboration with the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Desert Research Institute, a nonprofit research campus of the Nevada System of Higher Education.

Microbial life at −13 °C in the brine of an ice-sealed Antarctic lake, PNAS

Astrobiology