Exoplanet Discovery Database ExoFOP Reaches 1 Million Files And Counting

Discovering an exoplanet doesn’t mean having one, definitive eureka moment. Instead, it requires multiple observations, sometimes from multiple observatories, and the scientific community coming together in agreement to finally confirm its existence.

To facilitate those vital follow-up observations, the NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI) created the Exoplanet Follow-up Observing Program (ExoFOP) to help researchers collaborate and share observational data to confirm exoplanet candidates.

On March 3, the database surpassed one million user-submitted data files, relying solely on voluntary submissions from more than 1,700 registered individuals. Of the nearly 6,000 exoplanets confirmed thus far, data shared by the community through ExoFOP has contributed to approximately 4,000 of them.

“This milestone of one million files is exemplary of how the community is pulling together to try to answer questions like what is out there on other worlds and where life comes from,” said David Ciardi, NExScI Deputy Director and ExoFOP lead. “These questions that we’re asking don’t belong just to one person, they belong to everybody.”

The program was started in 2008 to support the mission team for NASA’s Kepler space telescope, but it quickly grew to include the entire astronomy community with the renewed Kepler mission K2 and the integration of data from other observatories like TESS.

With the number of confirmed exoplanets quickly approaching 6,000, it can be hard to imagine a time when only a handful were known. For ExoFOP lead developer Megan Crane, those days are not as far behind as we may think.

When it was first built, each entry in the database only accommodated one exoplanet around one host star, said Crane. “We always look back at that time and laugh. We should have known you could have multiple planets around stars. It’s been so cool to see ExoFOP grow over the years.”

Crane then rebuilt the entire database during the few months in the winter when the Kepler stars were not observable from Earth. She said she enjoys the new challenges that arise as the field grows.

“More data, new characteristics, multiple planets—these are the best parts about working so closely with ExoFOP users. Our community is highly invested in the project, and that makes it easy to build the best possible tool for them,” said Crane.

In a practice known as “open science,” the field of astronomy is trending towards more collaborative efforts and communal sharing of data. ExoFOP is one such example of this practice, as it encourages users to share their own observations and analyses with the community.

“Today’s missions are producing so much data, in every subfield from exoplanets to galaxies, to cosmology or supernovae, that the only way that we can produce results is if we are more effective and efficient in how we handle the data and work together as a community,” said Ciardi.

The goal of ExoFOP is to help astronomers from across the world collaborate with people and in ways they may not have access to otherwise. Using ExoFOP, they can see what observations have already been done and then build upon each other’s work almost instantly. With thousands of exoplanets and thousands more possible candidates, there is plenty of work to share.

“One of our challenges for the project is dealing with the high amount of data that people are uploading. It never really occurred to me how big ExoFOP would get,” said Crane. “One million files submitted by our community—that’s why we’re doing this. I never would have dreamed that would have happened when we started this 15 years ago.”

For the ExoFOP team, counting down to the millionth file was a bit like a quiet, mysterious New Year’s Eve countdown, waiting to see which user would upload their work and unknowingly cross the milestone.

“We were keeping track of the number internally, checking every few days. Starting around 999,000 we were all pretty excited,” said Crane.

To celebrate, the team sent out special-edition ExoFOP mugs, complete with smiley face planets, to the most prolific contributors to the database.

“The success of ExoFOP has been the result of the partnerships with NASA missions and the community,” said Ciardi. “We worked hard with the community and the missions to have ExoFOP do what they needed it to do—and through those partnerships, usage of ExoFOP grew.”

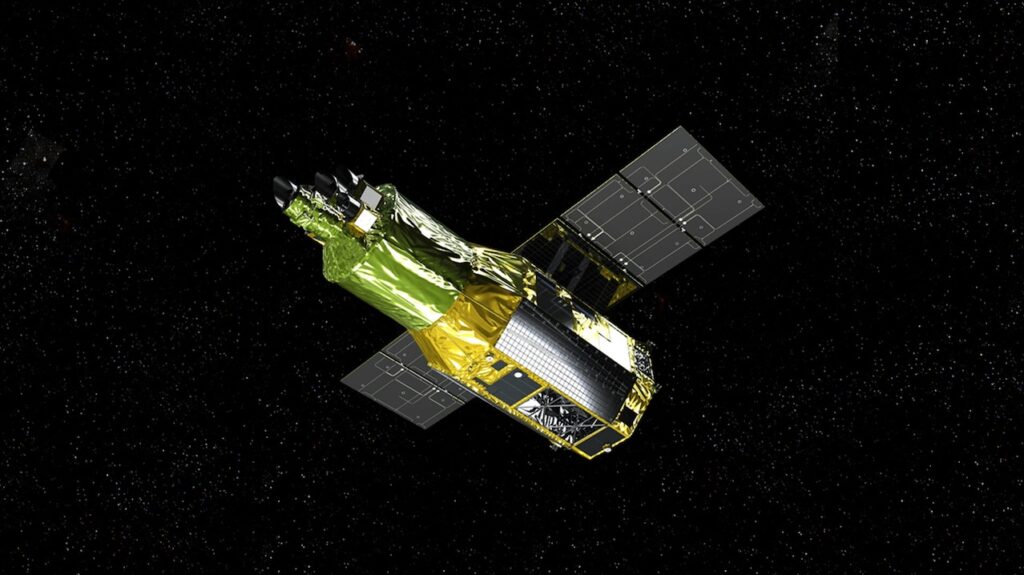

With new missions on the horizon, such as ESA’s Ariel and NASA’s Pandora and Habitable Worlds Observatory, the ExoFOP team is looking forward to incorporating more data and enabling the discovery and confirmation of even more exoplanets.

“It’s all about maximizing scientific return from these missions. With an ocean of data to dive into, there are constantly new things being found in old data,” said Jessie Christiansen, Chief Scientist of NExScI. “This milestone just goes to show how valuable of a resource ExoFOP is to the community.”

IPAC is a science and data center for astrophysics and planetary science located on the Caltech campus in Pasadena, CA. NASA Exoplanet Science Institute (NExScI), a part of IPAC, is a science operations and analysis service organization for NASA Exoplanet Exploration Program (ExEP) projects, and the scientists and engineers that use them. NExScI facilitates the timely and successful execution of exoplanet science by providing software infrastructure, science operations, and consulting to ExEP projects and their user communities.

The Exoplanet Follow-up Observing Program (ExoFOP) is designed to optimize resources and facilitate collaboration in follow-up studies of exoplanet candidates. ExoFOP serves as a repository for project and community-gathered data by allowing upload and display of data and derived astrophysical parameters. ExoFOP contains stellar parameters from the TESS Input Catalog (TIC), which is served by the Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes (MAST), and planet parameters from the NASA Exoplanet Archive.

Astrobiology, Astronomy, exoplanet,