Keith Cowing’s Devon Island Journal – 27 July 2007: Polar Deserts and Global TV

3:00 pm EDT 27 July 2007

I am sitting in a Lincoln Towne Car limo headed home from downtown Washington, DC after spending half a day doing TV interviews at CNN and Fox. A week ago – almost to the minute – I was riding aboard an ATV (All Terrain Vehicle) toward a dusty landing strip on Devon Island, less than a thousand miles from the North Pole.

The last week has been somewhat of a blur. With my business partner in town from Canada for a surprise trip (I found out about it while I was still up north) to hold some meetings – and all of this drunk astronaut nonsense – I have had no time to finish up my Devon Island journals – much less get any real work done.

Keith Cowing, sitting aboard a Twin Otter, prepares for the long journey home from Devon Island – exactly one week earlier – to the hour

This is not the first time a trip from remote Devon Island has collided with the modern world of telecommunications. In 2003, I had only been home when, as I wrote at the time: “Miles O’Brien (who has also visited Devon Island) set me up for the initial appearance. I was still unpacking my things and readjusting my brain to a green humid environment – and large numbers of people. I normally don’t go out of my way for make-up but this time I needed it. As a result of being outside in unusually warm weather I have quite the arctic suntan – and a red nose to go with it. Had they not subdued the redness I would have looked like a circus clown.”

This year I did not have a red nose, but I did have a nice tan. The make-up people did not need to do much work on me (not that it ever really helps, in my opinion).

Alas, in 2003, the interview (and many others that followed) had to do with a more serious topic: the Columbia Accident Investigation Board’s activities. Flash forward 4 years and I find myself (as do all other space talking heads) commenting on allegations of drunken astronauts, sabotaged space station computers, and bizarre astronaut love triangles.

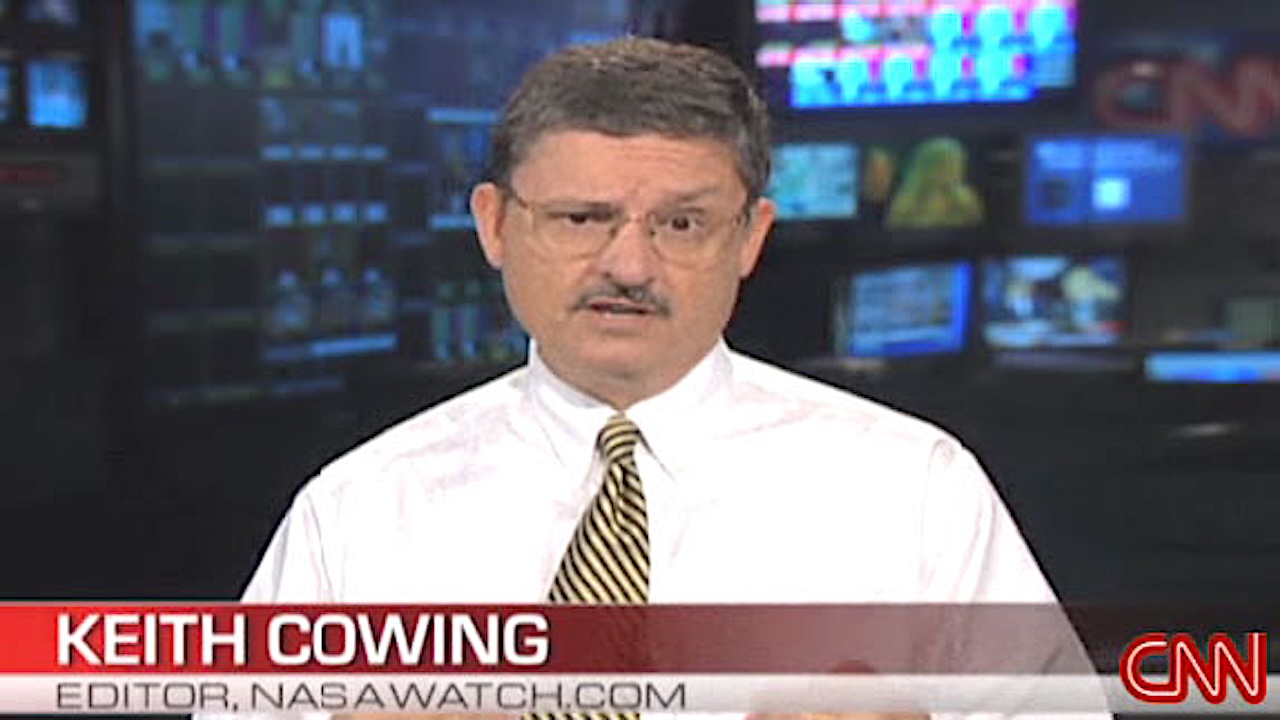

July 2003: One of many TV appearances done in conjunction with the CAIB report. After a month in the arctic wearing work clothes it was rather odd to sit in a TV studio wearing a tie.

I have done TV (usually on short notice) hundreds of times by now. As such, the routine of sitting in the chair with an earpiece in front of a camera and bright lights – with no one else in the room – talking to someone thousands of miles a way – while millions of people listen in – is rather familiar.

But that doesn’t mean I am not always thinking about where I am, what I am doing, and where it is I am supposed to fit in the bigger picture. What is different this time is that I just returned from my third mission (if you will) to a place not unlike another planet. And for the second time I have been immediately thrown into the global commons of news and other nonsense before I have had a chance to readapt to the world I live in.

Now, don’t think that this juxtaposition upsets me. Oh no – quite the contrary: it is a rare chance for anyone to experience such extremes and I savor the fleeting experience immensely – however jarring, annoying, and exciting it may be – simultaneously.

I used my iPhone to pull up something I wrote back in 2003 – an epilog I wrote regarding my second trip to Devon Island. It still resonates with me today:

“Last year’s trip to Devon Island was a remarkable adventure to an unknown and mysterious place. This year’s trip, while almost as long and varied in experiences to the same amazing place, was a return to terra cognita. A twist on Tom Wolfe’s admonition that ‘you can never go home again”. While I had returned to this place, it was the same. I was different.

This was my second mission to an alien place. Astronauts have to face this too in the course of their careers. Before I left, I asked astronaut Bill Readdy. Readdy has flown in space 3 times. I asked him what it was like to go back into space a second – and a third time. He told me “the saddest part of any mission for me is those moments that follow the euphoria of having accomplished what you set out to, having experienced (again) the sights, sounds, feeling and weightlessness which all combine into the magic of spaceflight. The thought that you might never return to experience it again hurts extremely.

I have been to Devon Island twice. I don’t know if I will ever be here again. As such, I need to drink in every last moment before I leave – perhaps for the last time. Last year I swore that I would return. This year I did just that. Now I must face the prospect of never seeing this place – or touching the greenhouse that all of us spent so much time, effort, money, and sheer determination, to construct in this most improbable location.

In a way, I suppose, traveling to such a remote and potentially hostile place embodies the old saying that the journey is far more important than the destination. Yet the destination is place where you pause and reflect upon the most memorable thoughts about the journey.

As is the case with space travel, I am certain climbers who have summited Everest, or climbed a big wall in Yosemite, or have dived to the depths of the ocean experience much the same thing. In some cases, the time spent at the destination is measured in square feet – and minutes – perhaps hours. I have been lavished with a total of 7 weeks thus far.

It was improbable enough that I went there once. Twice was just gravy. Again, the experience of being there is fleeting in terms of the actual hours, days, and weeks spent here. Yet one’s mind is always recording, sampling, savoring, digesting places like this for play back over the course of a lifetime.

The people who first trod on this island did so in search food and shelter. Later, people would load up ships and sail these waters and traverse these lands – and then disappear. After that, oil and mineral surveyors passed through. Now we are here – in an attempt to learn how to work on Mars. Yet we are all explorers in one way or another.

While my tasks on Devon Island focused on building a greenhouse and going out on traverses, I have to ask myself if I was truly “exploring”. The answer is an easy one: yes. While others have posted journal entries during previous seasons, no one has done such an extensive job of relaying experiences as have I and my business partner Marc Boucher.

As we built the greenhouse we did something, to my knowledge, that no one has ever built a greenhouse in such a hostile location and then outfitted it such that it can be operated like a spacecraft. The idea started in my head. Many others helped me make it happen. Together we explored new territory – both physically and technically – that no one has trod before. In so doing we explored territory – physical and operational – that no one had explored before.

Just being here is exploring as well. While this Island is the largest uninhabited island on Earth, it has been visited for millennia. Given its isolation and harsh climate, I doubt that every square centimeter has been trod upon by human feet. As such, you explore virgin territory by virtue of just wandering a few kilometers out of base camp.

Collectively, we are pursuing a variety of scientific, engineering, operational, experiential, and cultural frontiers – exploring along the way. And these exploits tend to draw a certain type of people. While I would be remiss in mentioning the vast diversity of backgrounds that our team members have, there are certain characteristics that resonate with those who come back for additional visits. To be succinct, being on Devon Island is like being given a chance to perch on the edge of a frontier. There aren’t that many left on the surface of this planet, so this one is extra special.

I’d hop in a Shuttle in a heartbeat. I’d have flown the day after Columbia was lost should the chance have appeared. Of course since this is rather improbable, I have to satisfy myself with terrestrial adventures.”

This year I built upon these previous experiences and accomplishments. I managed to bring several friends along with me to experience these things as well – and to help me expand upon the task of communicating these adventures with a broader audience.

I do not know if I will return to Devon Island. Yet something tells me that this is not the last time I will find myself in such a remote and exhilarating place – with such amazing people – all engaged in such an exciting, ongoing adventure.

About Devon Island, The Haughton-Mars Project, and the Mars Institute

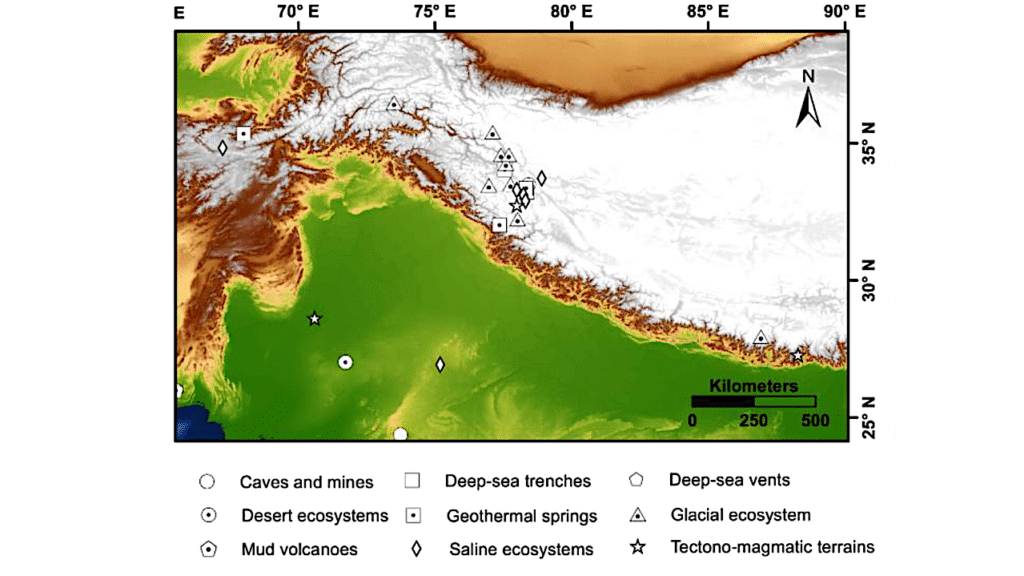

The Haughton-Mars Project (HMP) is an international interdisciplinary field research project centered on the scientific study of the Haughton impact structure and surrounding terrain, Devon Island, high arctic, viewed as a terrestrial analog for Mars. The rocky polar desert setting, geologic features and biological attributes of the site offer unique insights into the possible evolution of Mars – in particular the history of water and of past climates on Mars, the effects of impacts on Earth and on other planets, and the possibilities and limits of life in extreme environments. In parallel with its science program, the HMP supports an exploration program aimed at developing new technologies, strategies, humans factors experience, and field-based operational know-how key to planning the future exploration of the Moon, Mars and other planets by robots and humans. The HMP managed jointly by the Mars Institute and by the SETI Institute.

Astrobiology,