Europa Clipper Radar Instrument Proves Itself at Mars

The agency’s largest interplanetary probe tested its radar during a Mars flyby. The results include a detailed image and bode well for the mission at Jupiter’s moon Europa.

As it soared past Mars in March, NASA’s Europa Clipper conducted a critical radar test that had been impossible to accomplish on Earth. Now that mission scientists have studied the full stream of data, they can declare success: The radar performed just as expected, bouncing and receiving signals off the region around Mars’ equator without a hitch.

Called REASON (Radar for Europa Assessment and Sounding: Ocean to Near-surface), the radar instrument will “see” into Europa’s icy shell, which may have pockets of water inside. The radar may even be able to detect the ocean beneath the shell of Jupiter’s fourth-largest moon.

“We got everything out of the flyby that we dreamed,” said Don Blankenship, principal investigator of the radar instrument, of the University of Texas at Austin. “The goal was to determine the radar’s readiness for the Europa mission, and it worked. Every part of the instrument proved itself to do exactly what we intended.”

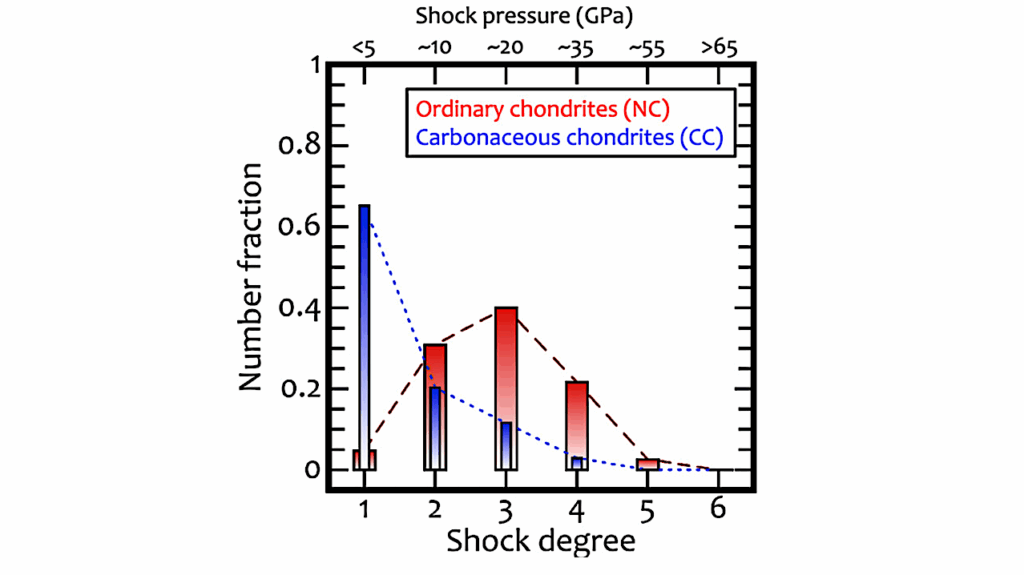

Europa Clipper’s radar instrument received echoes of its very-high-frequency radar signals that bounced off Mars and were processed to develop this radargram. What looks like a skyline is the outline of the topography beneath the spacecraft. Credit: NASA Larger image

The radar will help scientists understand how the ice may capture materials from the ocean and transfer them to the surface of the moon. Above ground, the instrument will help to study elements of Europa’s topography, such as ridges, so scientists can examine how they relate to features that REASON images beneath the surface.

In this artist’s concept, Europa Clipper’s radar antennas — seen at the lower edge of the solar panels — are fully deployed. The antennas are key components of the spacecraft’s radar instrument, called REASON. Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech

Limits of Earth

Europa Clipper has an unusual radar setup for an interplanetary spacecraft: REASON uses two pairs of slender antennas that jut out from the solar arrays, spanning a distance of about 58 feet (17.6 meters). Those arrays themselves are huge — from tip to tip, the size of a basketball court — so they can catch as much light as possible at Europa, which gets about 1/25th the sunlight as Earth.

The instrument team conducted all the testing that was possible prior to the spacecraft’s launch from NASA’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida on Oct. 14, 2024. During development, engineers at the agency’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California even took the work outdoors, using open-air towers on a plateau above JPL to stretch out and test engineering models of the instrument’s spindly high-frequency and more compact very-high-frequency antennas.

But once the actual flight hardware was built, it needed to be kept sterile and could be tested only in an enclosed area. Engineers used the giant High Bay 1 clean room at JPL, where the spacecraft was assembled, to test the instrument piece by piece. To test the “echo,” or the bounceback of REASON’s signals, however, they’d have needed a chamber about 250 feet (76 meters) long — nearly three-quarters the length of a football field.

Europa Clipper’s radar instrument received echoes of its very-high-frequency radar signals that bounced off Mars and were processed to develop this radargram. What looks like a skyline is the outline of the topography beneath the spacecraft

Enter Mars

The mission’s primary goal in flying by Mars on March 1, less than five months after launch, was to use the planet’s gravitational pull to reshape the spacecraft’s trajectory. But it also presented opportunities to calibrate the spacecraft’s infrared camera and perform a dry run of the radar instrument over terrain NASA scientists have been studying for decades.

As Europa Clipper zipped by the volcanic plains of the Red Planet — starting at 3,100 miles (5,000 kilometers) down to 550 miles (884 kilometers) above the surface — REASON sent and received radio waves for about 40 minutes. In comparison, at Europa the instrument will operate as close as 16 miles (25 kilometers) from the moon’s surface.

All told, engineers were able to collect 60 gigabytes of rich data from the instrument. Almost immediately, they could tell REASON was working well. The flight team scheduled the full dataset to download, starting in mid-May. Scientists relished the opportunity over the next couple of months to examine the information in detail and compare notes.

“The engineers were excited that their test worked so perfectly,” said JPL’s Trina Ray, Europa Clipper deputy science manager. “All of us who had worked so hard to make this test happen — and the scientists seeing the data for the first time — were ecstatic, saying, ‘Oh, look at this! Oh, look at that!’ Now, the science team is getting a head start on learning how to process the data and understand the instrument’s behavior compared to models. They are exercising those muscles just like they will out at Europa.”

Europa Clipper’s total journey to reach the icy moon will be about 1.8 billion miles (2.9 billion kilometers) and includes one more gravity assist — using Earth — in 2026. The spacecraft is currently about 280 million miles (450 million kilometers) from Earth.

More About Europa Clipper

Europa Clipper’s three main science objectives are to determine the thickness of the moon’s icy shell and its interactions with the ocean below, to investigate its composition, and to characterize its geology. The mission’s detailed exploration of Europa will help scientists better understand the astrobiological potential for habitable worlds beyond our planet.

Managed by Caltech in Pasadena, California, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California leads the development of the Europa Clipper mission in partnership with the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Laurel, Maryland, for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington. APL designed the main spacecraft body in collaboration with JPL and NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama, and Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. The Planetary Missions Program Office at NASA Marshall executes program management of the Europa Clipper mission. NASA’s Launch Services Program, based at NASA Kennedy, managed the launch service for the Europa Clipper spacecraft. The REASON radar investigation is led by the University of Texas at Austin.

Find more information about Europa Clipper here: https://science.nasa.gov/mission/europa-clipper/