Green Ice, Ravens, Ice Caves And The Movie “Contact”

Towards the end of our summer expedition while flying back to Eureka from our camp on Axel Heiberg, I spotted a lake with what appeared to be green ice on it.

Seeing ice this color is particularly interesting since the color green tends to make an aquatic ecologist think of life – microbial life with chlorophyll. It also reminded me of a question I first heard posed by Chris McKay, a scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in California. During one of his presentations, Chris asked the question “why isn’t Greenland green? Why is the ice-cap of Greenland, or the Antarctic for that matter, not covered with photosynthetic organisms tinting the snow and ice green despite the abundant availability of summer sun and 90% of the planet’s fresh water?”

This observation points out a profound ecological reality for life on Earth – just having water available is not enough – it must be liquid water in order for life to carry out the chemistry of life. The snow and ice on the ice-caps do not support an abundance of photosynthesizers mainly because the water is present as a solid (ice) and for all practical purposes is not available for life to use. Despite the cubic kilometers of water within these ice-caps, they are vast frozen deserts. I did not have time to drop down to get a sample of the bright green ice, but as green as it was, I suspect that the tint must have been a result of the presence of chlorophyll. The difference between this lake ice and the ice-caps of Greenland and Antarctica being the abundance of liquid water on and within the small ice-cover as it melted away.

A couple of days after arriving in Eureka I travelled with Dr. Chris Omelon by ATV along a sandstone ridge in order to collect samples at several locations. Chris has been studying the microorganisms that colonize the pore space just below the surface of the sandstone rocks. These microorganisms are known as endoliths. I have a few images of these communities in my Arctic Photo album and in an antarctic album online at astrobiology.com in volumes 2 and 3. Along the way we met wildlife research biologist Dr. Dave Mech who was up again this summer observing and studying the wolves of Ellesmere Island. After a a bit of talk regarding his research, he told Chris and I about a raven that had been hanging around his study site. I did not think I would actually see it, but a short while later I met this very friendly raven, which you see perched on my boot at the end of my outstretched legs in the picture above. It was a pretty funny bird, and while Chris collected samples a few hundred meters away, it kept me company for about 35 min or so before wandering back over to the nearby wolf den (which Dave informed us was home to 5 pups and 7 other wolves). Encounters with nature like this do not come around too often so I counted myself lucky.

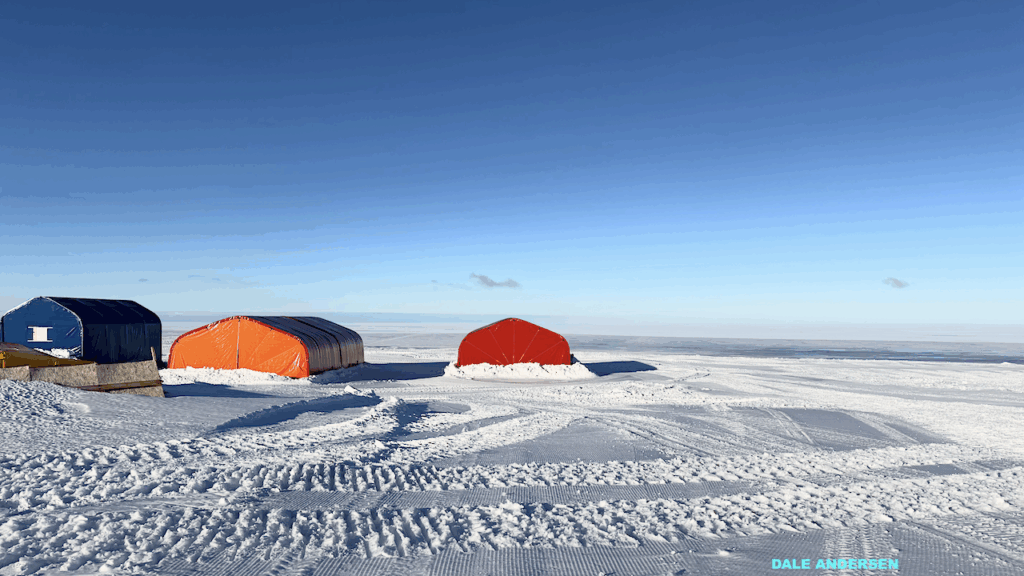

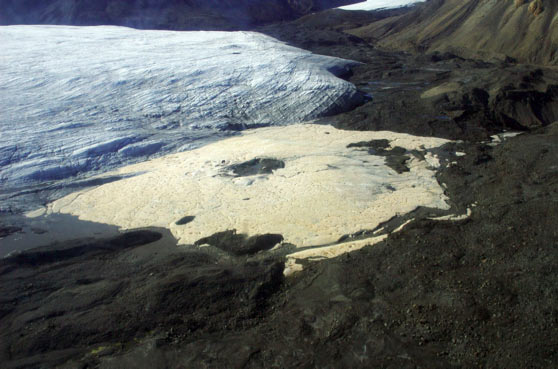

Residual icing/glacial discharge at Skaer Fiord

A few days before heading over to Eureka, we were checking out one of the spring sites that Wayne Pollard and I have been observing for the last couple of years. Springs are rare in regions of thick permafrost, particularly if the flow occurs year round. We know this one is flowing in late April, but we are not sure if it flows throughout the year. We hope to be onsite very early next year in order to see what the flow is doing (or not…). The discharge at the front of the glacier had formed a residual icing and a large icing blister which was hollow underneath and large enough for us to go inside.

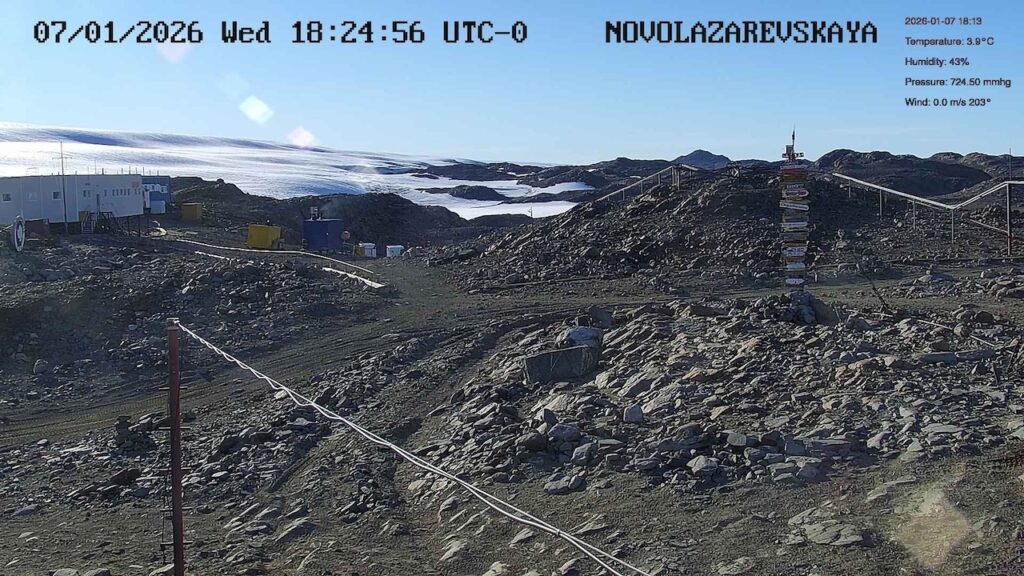

Wayne Pollard, inside the icing blister at Skaer Fiord

It was like walking into an art gallery! The light diffusing from the ice above was red and green from the minerals associated with the water and on the floor was a garden of very delicate crystals that were 6-8 inches tall. The slightly orange-red hued crystals were quite beautiful and the muffled sound within the ice cave provided an erie background to it all. Someone mentioned that it reminded them of the scene from the film Alien when they first discovered the ‘pods’. My first impression was of a diorama I had seen in the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History that depicted Ediacara biota that dominated the late Precambrian marine ecosystem.

While waiting for everyone to regroup, the helicopter pilot Dave Bursey (of Universal Helicopters Newfoundland Limited) and I began talking about life in extreme environments. I mentioned that I was with the SETI Institute in Mountain View, CA and out of curiosity I asked Dave if he had seen the film Contact a story with SETI as its main theme.

Dave laughed and said that he had, and not only that, he had helped with the filming! As it turned out, he flew the helo that obtained footage in Gros Morne National Park located on the west coast of Newfoundland. Dave worked with Ken Ralston the senior visual effects supervisor for the film.

Often we travel to remote places to investigate life in extreme environments, to help us better understand life on our own world and perhaps to help us gain insight about the possibilities for life elsewhere and I feel particularly lucky to be able to experience these unique settings. But so much happens along the way, meeting interesting people and sharing their experiences in life, witnessing nature in its rawest, unfiltered form; and it is so true, its not always the final destination that is important, but the voyage that takes you there.