Possible Marker Of Life Spotted On Venus

An international team of astronomers today announced the discovery of a rare molecule — phosphine — in the clouds of Venus. On Earth, this gas is only made industrially or by microbes that thrive in oxygen-free environments.

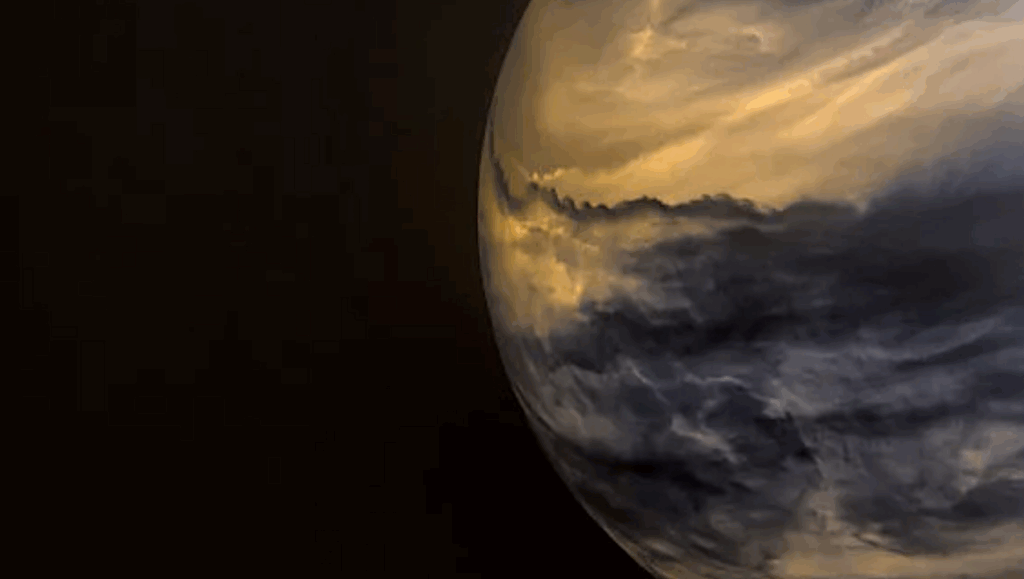

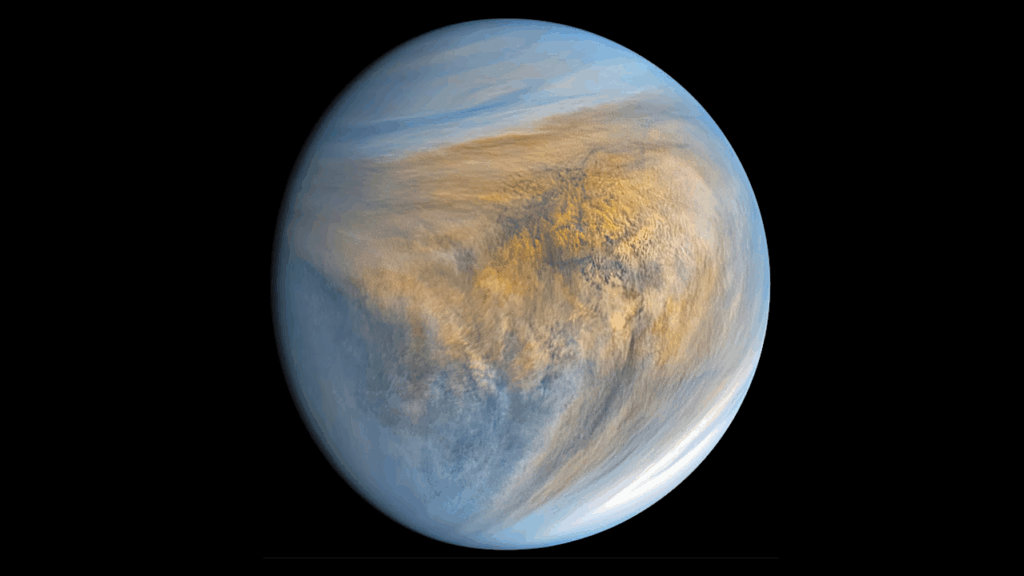

Astronomers have speculated for decades that high clouds on Venus could offer a home for microbes — floating free of the scorching surface but needing to tolerate very high acidity. The detection of phosphine could point to such extra-terrestrial “aerial” life.

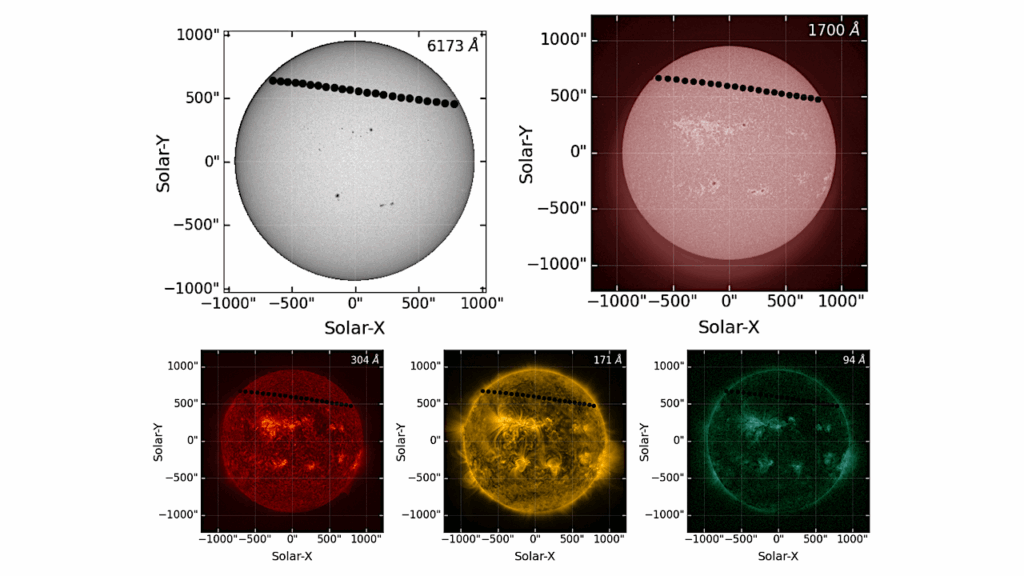

“When we got the first hints of phosphine in Venus’s spectrum, it was a shock!,” says team leader Jane Greaves of Cardiff University in the UK, who first spotted signs of phosphine (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phosphine) in observations from the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT, https://www.eaobservatory.org/jcmt), operated by the East Asian Observatory, in Hawaii. Confirming their discovery required using 45 antennas of the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA, https://www.eso.org/public/teles-instr/alma) in Chile, a more sensitive telescope in which the European Southern Observatory (ESO) is a partner. Both facilities observed Venus at a wavelength of about 1 millimetre, much longer than the human eye can see — only telescopes at high altitude can detect it effectively.

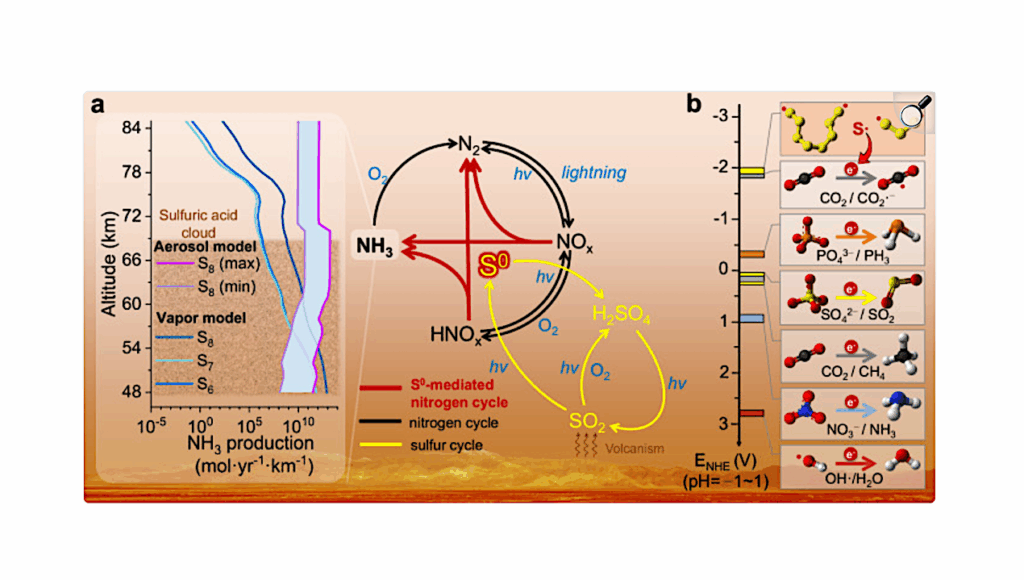

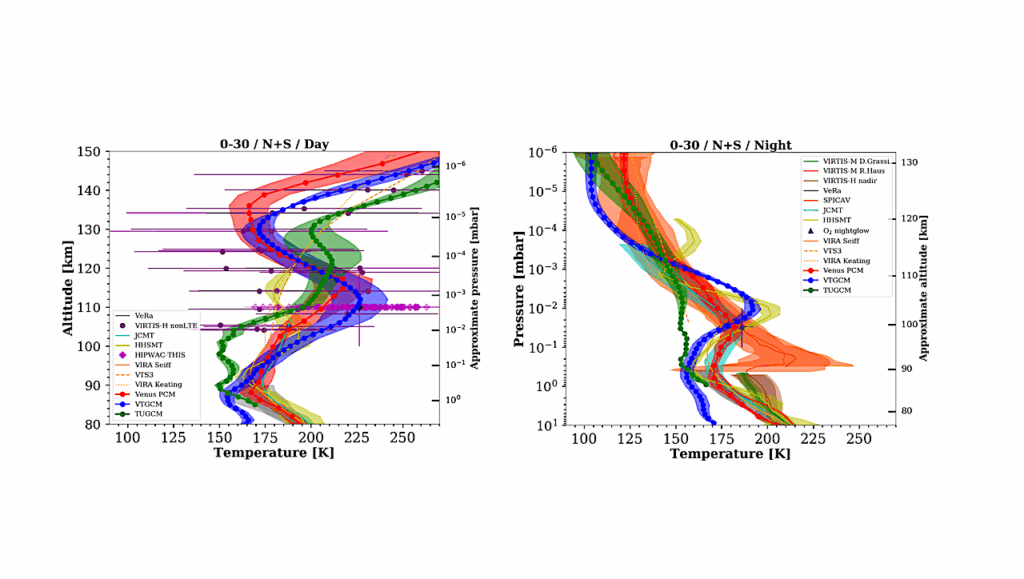

The international team, which includes researchers from the UK, US and Japan, estimates that phosphine exists in Venus’s clouds at a small concentration, only about 20 molecules in every billion. Following their observations, they ran calculations to see whether these amounts could come from natural non-biological processes on the planet. Some ideas included sunlight, minerals blown upwards from the surface, volcanoes, or lightning, but none of these could make anywhere near enough of it. These non-biological sources were found to make at most one 10,000th of the amount of phosphine that the telescopes saw.

To create the observed quantity of phosphine (which consists of hydrogen and phosphorus) on Venus, terrestrial organisms would only need to work at about 10% of their maximum productivity, according to the team. Earth bacteria are known to make phosphine: they take up phosphate from minerals or biological material, add hydrogen, and ultimately expel phosphine. Any organisms on Venus will probably be very different to their Earth cousins, but they too could be the source of phosphine in the atmosphere.

While the discovery of phosphine in Venus’s clouds came as a surprise, the researchers are confident in their detection. “To our great relief, the conditions were good at ALMA for follow-up observations while Venus was at a suitable angle to Earth. Processing the data was tricky, though, as ALMA isn’t usually looking for very subtle effects in very bright objects like Venus,” says team member Anita Richards of the UK ALMA Regional Centre and the University of Manchester. “In the end, we found that both observatories had seen the same thing — faint absorption at the right wavelength to be phosphine gas, where the molecules are backlit by the warmer clouds below,” adds Greaves, who led the study published today in Nature Astronomy.

Another team member, Clara Sousa Silva of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US, has investigated (https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2018.1954) phosphine as a “biosignature” gas of non-oxygen-using life on planets around other stars, because normal chemistry makes so little of it. She comments: “Finding phosphine on Venus was an unexpected bonus! The discovery raises many questions, such as how any organisms could survive. On Earth, some microbes can cope with up to about 5% of acid in their environment — but the clouds of Venus are almost entirely made of acid.”

The team believes their discovery is significant because they can rule out many alternative ways to make phosphine, but they acknowledge that confirming the presence of “life” needs a lot more work. Although the high clouds of Venus have temperatures up to a pleasant 30 degrees Celsius, they are incredibly acidic — around 90% sulphuric acid — posing major issues for any microbes trying to survive there.

ESO astronomer and ALMA European Operations Manager Leonardo Testi, who did not participate in the new study, says: “The non-biological production of phosphine on Venus is excluded by our current understanding of phosphine chemistry in rocky planets’ atmospheres. Confirming the existence of life on Venus’s atmosphere would be a major breakthrough for astrobiology; thus, it is essential to follow-up on this exciting result with theoretical and observational studies to exclude the possibility that phosphine on rocky planets may also have a chemical origin different than on Earth.”

More observations of Venus and of rocky planets outside our solar system, including with ESO’s forthcoming Extremely Large Telescope, may help gather clues on how phosphine can originate on them and contribute to the search for signs of life beyond Earth.

Reference:

“Phosphine Gas in the Cloud Decks of Venus,” Jane S. Greaves et al., 2020 Sep. 14, Nature Astronomy [https://www.nature.com/natastron, preprint (PDF): https://www.eso.org/public/archives/releases/sciencepapers/eso2015/eso2015a.pdf]. The team is composed of Jane S. Greaves (School of Physics & Astronomy, Cardiff University, UK [Cardiff]), Anita M. S. Richards (Jodrell Bank Centre for Astrophysics, The University of Manchester, UK), William Bains (Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, USA [MIT]), Paul Rimmer (Department of Earth Sciences and Cavendish Astrophysics, University of Cambridge and MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Cambridge, UK), Hideo Sagawa (Department of Astrophysics and Atmospheric Science, Kyoto Sangyo University, Japan), David L. Clements (Department of Physics, Imperial College London, UK [Imperial]), Sara Seager (MIT), Janusz J. Petkowski (MIT), Clara Sousa-Silva (MIT), Sukrit Ranjan (MIT), Emily Drabek-Maunder (Cardiff and Royal Observatory Greenwich, London, UK), Helen J. Fraser (School of Physical Sciences, The Open University, Milton Keynes, UK), Annabel Cartwright (Cardiff), Ingo Mueller-Wodarg (Imperial), Zhuchang Zhan (MIT), Per Friberg (EAO/JCMT), Iain Coulson (EAO/JCMT), E’lisa Lee (EAO/JCMT) and Jim Hoge (EAO/JCMT).

Additional References:

* “The Venusian Lower Atmosphere Haze as a Depot for Desiccated Microbial Life: A Proposed Life Cycle for Persistence of the Venusian Aerial Biosphere,” Sara Seager et al, 2020 Aug. 13, Astrobiology [https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2020.2244].

* “Phosphine as a Biosignature Gas in Exoplanet Atmospheres,” Clara Sousa-Silva et al., 2020 Jan. 31, Astrobiology [https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/full/10.1089/ast.2018.1954].