How Earth’s Greenhouse Age Ended 66 Million Years Ago

A 66 million-year-old mystery behind how our planet transformed from a tropical greenhouse to the ice-capped world of today has been unravelled by scientists.

Their new study has revealed that Earth’s massive drop in temperature after the dinosaurs went extinct could have been caused by a large decrease in calcium levels in the ocean.

An international team of experts led by the University of Southampton discovered that concentrations of calcium in the sea dropped by more than half across the last 66 million years.

The study, published in Proceeding of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), showed that the dramatic calcium shift may have sucked carbon dioxide – a major greenhouse gas – out of the atmosphere, driving global cooling.

Lead author Dr David Evans, an ocean and earth scientist from Southampton, said that large changes in the composition of seawater chemistry may have been a key driver for climate change.

He added: “Our results show that dissolved calcium levels were twice as high at the start of the Cenozoic Era, shortly after dinosaurs roamed the planet, compared to today.

“When these levels were high, the oceans worked differently, acting to store less carbon in seawater and releasing carbon dioxide into the air.

“As those levels decreased, CO2 was sucked out of the atmosphere, and the Earth’s temperature followed, dropping our climate by as much as 15 to 20 degrees Celsius.”

The Southampton researchers behind the study worked in collaboration with scientists from China, the USA, Israel, Denmark, Germany, Belgium and Netherlands.

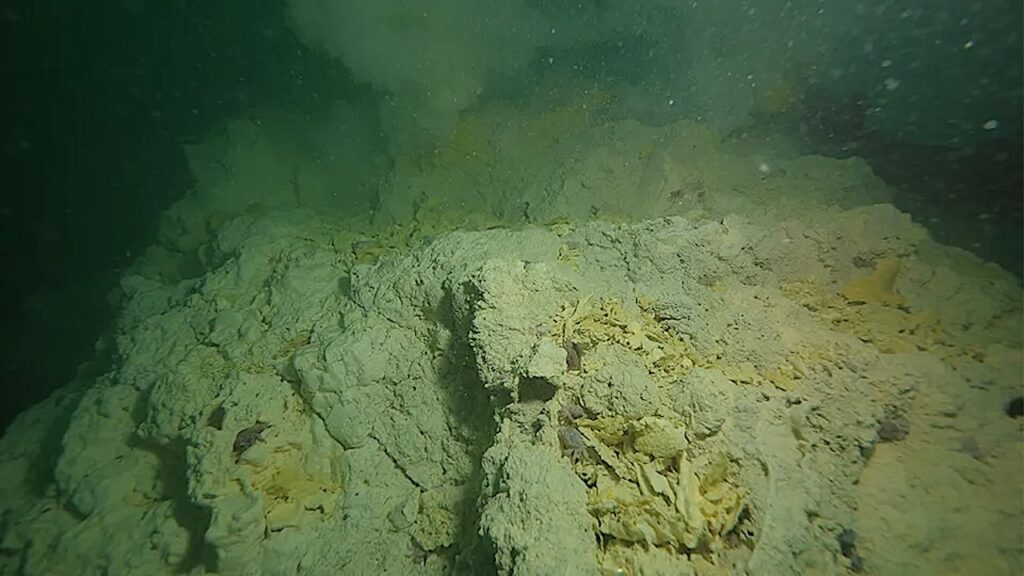

They used fossilised remains of tiny sea creatures dug up from sediments at the seafloor to construct the most detailed record of ocean chemistry to date.

The chemical composition of the fossils, called foraminifera, showed a close link between the amount of calcium in seawater and the level of carbon dioxide in the air.

Using computer-made models, the team showed that high levels of calcium change how much carbon is “fixed” by marine life, such as corals and plankton, said Dr Evans.

This effectively locked it away from the ocean and atmosphere by storing it in sediments on the seafloor.

As dissolved calcium levels decreased across millions of years, it altered how these organisms produced and buried calcium carbonate on the seafloor, added co-author Dr Xiaoli Zhou of Tongji University in China.

She added: “The process effectively pulls carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere and locks it away.

“This shift could have changed the composition of the atmosphere, effectively turning down the planet’s thermostat.”

The experts also revealed that the drop in calcium closely matched the slowing down of seafloor spreading – the volcanic process that continuously creates new ocean floors.

As the rate of seafloor production slowed, the chemical exchange between the rocks and sea water changed, leading to a gradual decline in dissolved calcium concentrations, said co-author Professor Yair Rosenthal from Rutgers University, USA.

He added: “Seawater chemistry is typically viewed as something that responds to other factors that lead to changes in our climate, rather than being the cause itself.

“But our new evidence suggests that we must look to changing seawater chemistry to understand our planet’s climate history.

“It may be that changes in these deep Earth processes are ultimately responsible for much of the large climatic shifts that have taken place over geological time.”

Astrobiology,