Perspectives On Mars Sample Return: A Critical Resource For Planetary Science And Exploration

Mars Sample Return (MSR) has been the highest flagship mission priority in the last two Planetary Decadal Surveys of the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine (hereafter, “the National Academies”) and was the highest priority flagship for Mars in the Decadal Survey that preceded them.

This inspirational and challenging campaign, like the Apollo program’s returned lunar samples, will potentially revolutionize our understanding of Mars and help inform how other planets are explored. MSR’s technological advances will keep the NASA and European Space Agency at the forefront of planetary exploration, and data on returned samples will fill knowledge gaps for future human exploration.

Investigations of the ancient rocks collected in and around Jezero crater, as well as samples of the regolith and atmosphere, will be fundamentally different in scope, depth, and certainty from what is achievable with spaceborne observations. Returned Mars samples can address critical science issues including the discovery and characterization of ancient extraterrestrial life, prebiotic organic chemistry, the history of habitable planetary environments, planetary geological, geochemical, and geophysical evolution, orbital dynamics of bodies in the early Solar System, and the formation and evolution of atmospheres.

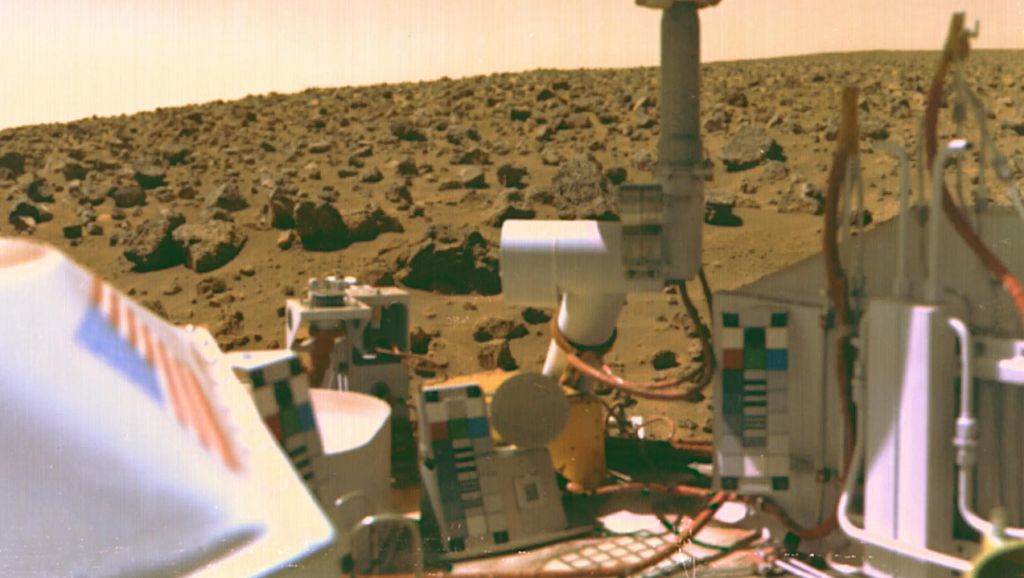

Mars has been a target of scientific interest for centuries, but the vision that we could collect, return, and investigate samples from Mars came to the forefront much more recently—spurred, in part, by debate as to whether the Viking landers detected evidence for life (1, 2). The modern era of robotic exploration of Mars, beginning in the 1990s, has been an unrivaled success story.

These spacecraft missions were guided by a philosophy that Mars exploration would be of greatest value if it were conducted as a program of strategically guided missions that orbit, land, and rove across the surface to understand martian geology, water and climate history, and the potential for the development of life beyond Earth.

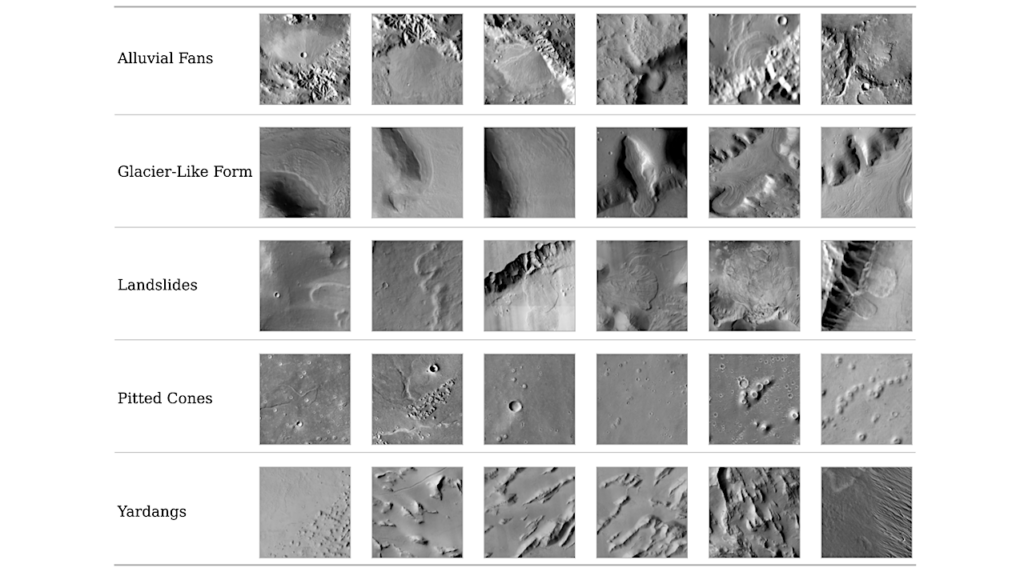

These robotic missions transformed the early view of Mars from one of a cold, dry, lava-covered planet unlikely to have harbored life to the current understanding that liquid water was present at the surface in the past and is likely present in the subsurface today, the climate was very likely once much warmer than it is today, and past conditions probably were habitable (3–5).

Although there are still many valuable measurements that can and should be made by orbiting, landed, and roving scientific payloads, we also recognize that there are analyses that either cannot be made with current remote-sensing technology or not with the equivalent fidelity of laboratory facilities on Earth.

If we are to address many of the most significant questions about Mars, including the possibility that life may have existed in that early warmer and wetter period and what that means for the origin of life on Earth (and elsewhere), analyzing returned martian samples will accelerate that process by decades for many subjects of interest. In doing so, samples from Mars will produce a significant step forward in scientific understanding of the planet and inform how we can best use robotic programs for future planetary exploration.

Sample return is also a long-term investment in science, because a significant portion of the returned material will be held securely for future generations who will develop new questions and measurement capabilities that will leapfrog what we can achieve now.

Perspectives on Mars Sample Return: A critical resource for planetary science and exploration, PNAS via PubMed (open access)

Astrobiology,