Machinery Behind Bacterial Nanowires Discovered

Almost all living things breathe oxygen to eliminate the excess electrons produced when nutrients are converted into energy. However, most microbes that mitigate pollution and climate change don’t have access to oxygen. Instead, these bacteria—buried underground or living deep under oceans—have developed a way to eliminate electrons by “breathing minerals” from the soil through tiny protein filaments called nanowires.

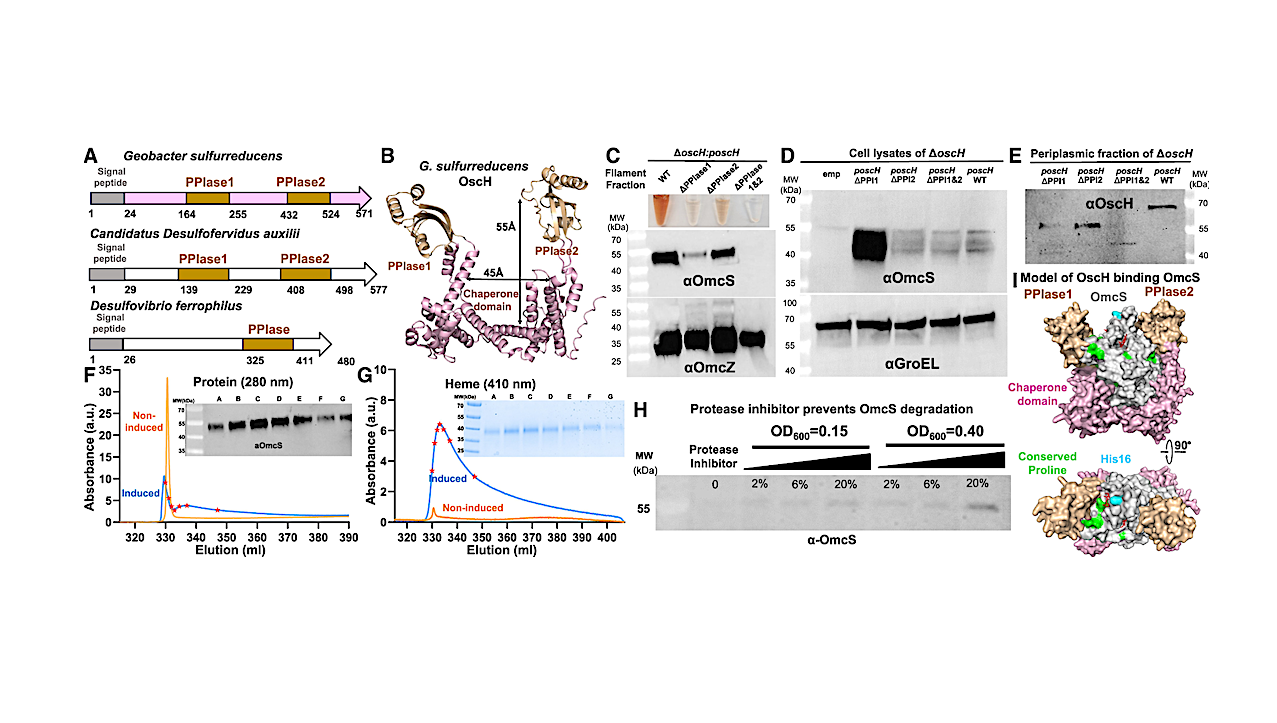

In previous research, a team led by Nikhil Malvankar, Associate Professor of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry at Yale’s Microbial Sciences Institute, showed that nanowires are made up of a chain of heme molecules, just like hemoglobin in our blood, thrust into the environment to move electrons. To leverage the power of these microbes, however, scientists need to know how those nanowires are assembled.

Graphical Abstract — ScienceDirect

The Yale team led by Cong Shen has now discovered the machinery that assembles the nanowires, making practical applications possible. Of the 111 heme proteins, only three are known to polymerize to become nanowires. Not only did the team identified the surrounding machinery that makes it possible for these proteins to become nanowires, but they also demonstrated that changing some of the machinery’s components can accelerate nanowire reproduction and bacterial growth. This is an important next step in engineering bacteria to efficiently produce electricity, clean pollutants from water, and lower atmospheric methane levels.

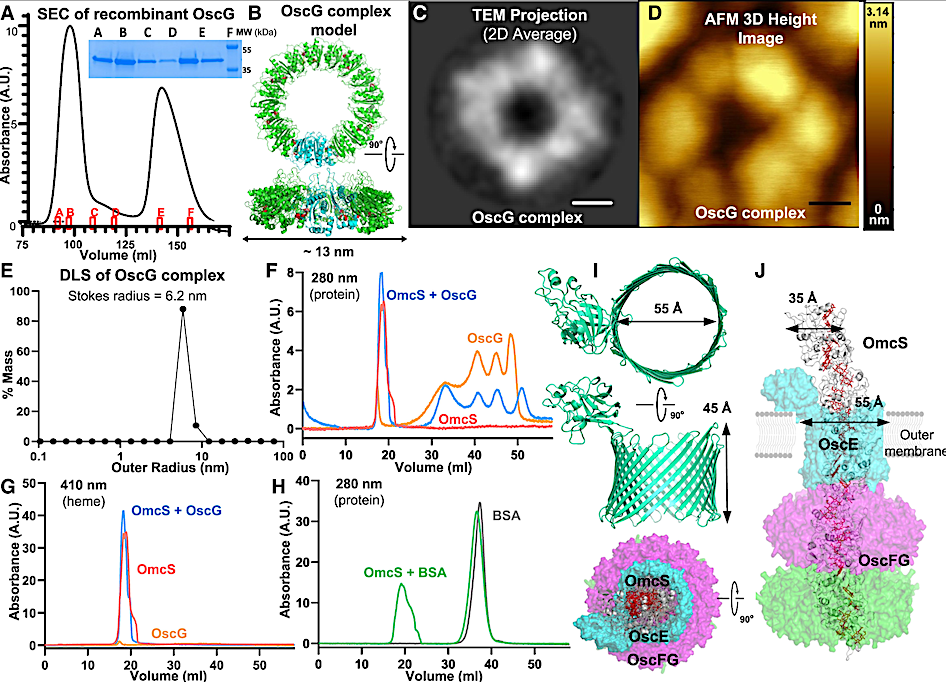

Figure 3. OscG forms a secretion channel-like ring structure and binds to OmcS nanowires (A) Recombinant OscG purified by SEC. Inset, Coomassie gel of OscG from marked positions. (B) OscG model (protomer in cyan, octamer in green) with DEAD-type motif (red). (C–E) OscG ring complex was revealed by (C), the 2D average of negative-stain TEM images; (D), the 3D height profile from the AFM image; and (E), the size distribution from the DLS. Scale bars for (C) 3 nm and (D) 20 nm. (F–H) The binding of OscG complex to OmcS homolog nanowire measured by (F), protein (280 nm) and (G), heme (410 nm) absorbance of SEC. (H)OmcS nanowires do not bind BSA. (I) AlphaFold models of OscE. (J) Simplified hypothetical model of the OscEFG channel. — ScienceDirect

The paper, published in Cell Chemical Biology, is co-authored by Malvankar lab members Aldo Salazar-Morales, Joey Erwin, Yangqi Gu, Anthony Coelho, Sibel Ebru Yalcin, and Fadel Samatey, and collaborators Prof. Kallol Gupta and Wonhyeuk Jung. Image credit: Ella Maru Studio.

A widespread and ancient bacterial machinery assembles cytochrome OmcS nanowires essential for extracellular electron transfer, ScienceDirect

Astrobiology