Modifying Genomes Of Tardigrades To Unravel Their Secrets

Some species of tardigrades are highly and unusually resilient to various extreme conditions fatal to most other forms of life.

The genetic basis for these exceptional abilities remains elusive. For the first time, researchers from the University of Tokyo successfully edited genes using the CRISPR technique in a highly resilient tardigrade species previously impossible to study with genome-editing tools. The successful delivery of CRISPR to an asexual tardigrade species directly produces gene-edited offspring. The design and editing of specific tardigrade genes allow researchers to investigate which are responsible for tardigrade resilience and how such resilience can work.

If you’ve heard about tardigrades, then you’ve no doubt heard about their uncommon abilities to survive things like extreme heat, cold, drought, and even the vacuum of space, which different members of the species possess. So naturally, they attract researchers keen to explore these novelties, not just out of curiosity, but also to look at what applications might one day be possible if we learn their secrets.

“To understand tardigrades’ superpowers, we first need to understand the way their genes function,” said Associate Professor Takekazu Kunieda from the Department of Biological Sciences. “My team and I have developed a method to edit genes — adding, removing or overwriting them — like you would do on computer data, in a very tolerant species of tardigrade, Ramazzottius varieornatus. This can now allow researchers to study tardigrade genetic traits as they might more established lab-based animals, such as fruit flies or nematodes.”

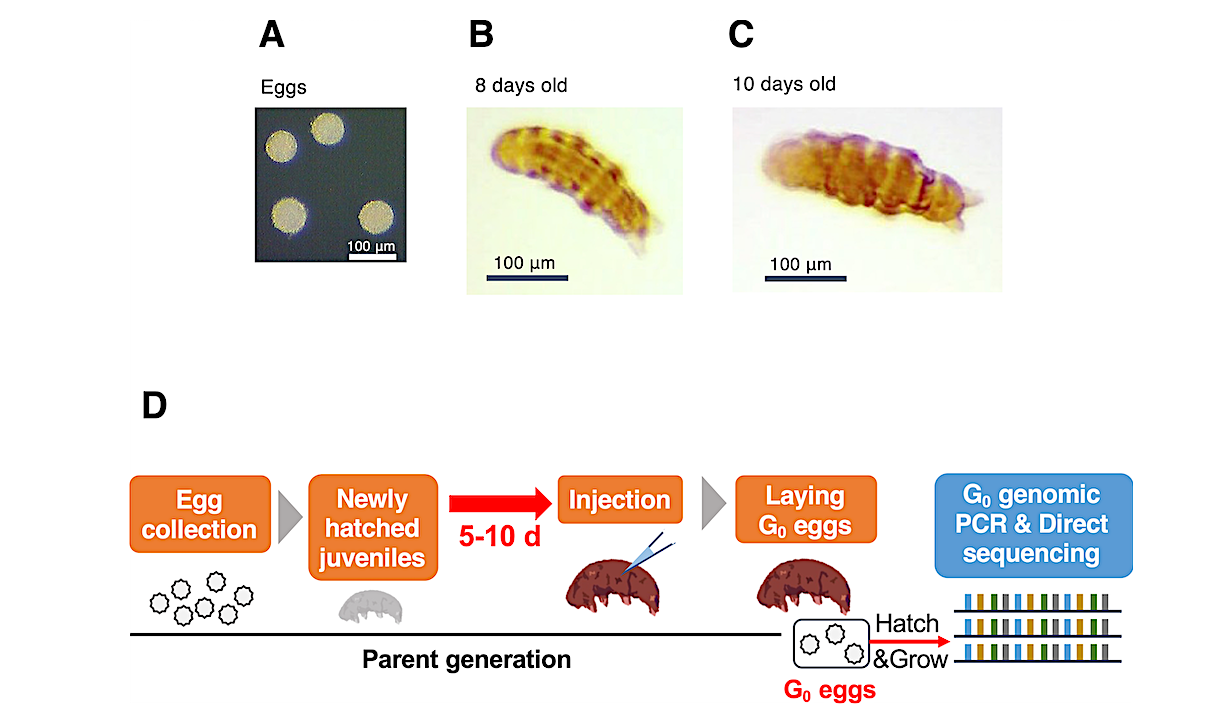

The team used a recently developed technique called direct parental CRISPR (DIPA-CRISPR), based on the now-famous CRISPR gene-editing technique, which can serve as a genetic scalpel to cut and modify specific genes more efficiently than ever before. DIPA-CRISPR has the advantage of being able to affect the genome of a target organism’s offspring and had previously been shown to work on insects, but this is the first time it’s been used on the noninsect organisms that include tardigrades. Ramazzottius varieornatus is an all-female species that reproduces asexually, and almost all offspring turned out to have two identical copies of the same edited code, unlike other animals, making it an ideal candidate for DIPA-CRISPR.

“We simply needed to inject CRISPR tools programmed to target specific genes for removal into the body of a parent to obtain modified offspring, known as ‘knock-out’ editing,” said Koyuki Kondo, project researcher at the time of the study (currently assistant professor at the Department of Life Science at Chiba Institute of Technology). “We could also obtain gene-modified offspring by injection of extra DNA fragments we want to include; this is called ‘knock-in’ editing. The availability of knock-in editing allows researchers to precisely edit tardigrade genomes, allowing them to, for example, control the way individual genes are expressed, or exhibit the genes’ functions.”

The main resilience trait this species demonstrates is their ability to survive extreme dehydration for long periods. This was previously shown to be partially due to a special kind of gel protein in their cells. And this trait is interesting as it has also been applied to human cells. Kunieda and other tardigrade researchers think it’s worth exploring whether something like an entire human organ could one day be successfully dehydrated and rehydrated without degradation. If that is possible, it could revolutionize the way organs are donated, transported and used in surgery to save lives.

“I understand some people feel anxious about gene editing, but we performed the gene-editing experiments under well-controlled conditions and secured the edited organisms in a closed compartment,” said Kunieda. “CRISPR can be an incredible tool for understanding life and aiding in useful applications that can positively impact the world. Tardigrades not only offer us a glimpse at what medical advances might be possible, but their range of remarkable traits means they had an incredible evolutionary story, one we hope to tell as we compare their genomes to closely related creatures using our new DIPA-CRIPSR-based technique.”

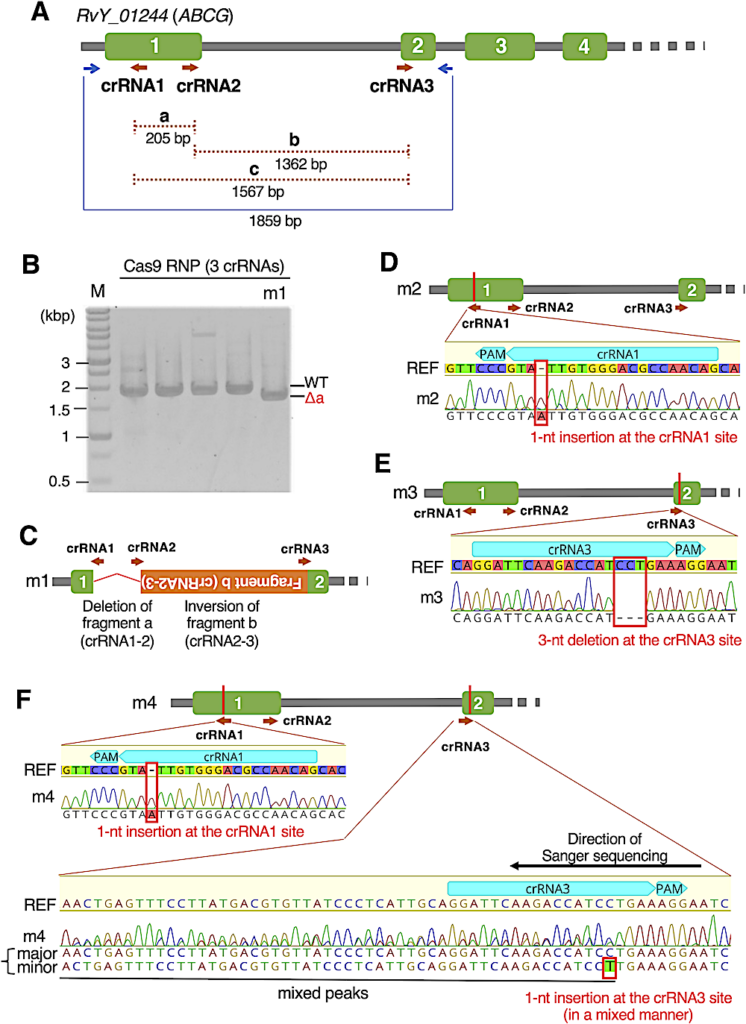

Generation of G0 progeny with gene editing at the RvY_01244 gene locus. (A) Schematic representation of the structure of the RvY_01244 (ABCG) gene, and the locations of three crRNAs (brown arrows) and genomic PCR primers (blue arrows). Green boxes represent exons and gray lines represent introns or intergenic regions. (B) A representative agarose gel image of genomic PCR amplicons derived from some G0 progeny. In this gel, the four samples on the left exhibited amplicons at the size expected from the unmodified genome (WT), while the right sample termed m1 exhibited a single band representing a shorter size (Δa) than WT, which roughly corresponds to the size with the deletion of fragment a (crRNA1–crRNA2). Note: The amplicon at the WT size was not detected in the m1 sample. (C–F) Gene-editing patterns in the four obtained gene-edited G0 individuals, such as complex editing (m1, C), a 1-nt insertion (m2, D), a 3-nt deletion (m3, E), and two 1-nt insertions (m4, F). (C) Red bent line represents the deletion of the intervening region between crRNA1 and crRNA2. Orange box represents the intervening DNA fragment between crRNA2 and crRNA3, which was re-inserted in the reverse orientation. (D–F) Schematic representation of the gene-edited location and electropherograms in direct Sanger sequencing of genomic PCR amplicons with the reference sequence (REF).

Journal article:

Koyuki Kondo, Akihiro Tanaka, Takekazu Kunieda. “Single-step generation of homozygous knockout/knock-in individuals in an extremotolerant parthenogenetic tardigrade using DIPA-CRISPR”, PLOS Genetics, DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1011298

Funding: his work was supported by Japan Society for the Promotion of Science JSPS KAKENHI Grant Numbers JP20H04332, JP20K20580, JP21H05279 (to TK). AT received a Grant-in-Aid for JSPS Fellows (JP21J11385).

Astrobiology, Genomics,