New Pieces In The Puzzle Of First Life On Earth

Microorganisms were the first forms of life on our planet. The clues are written in 3.5 billion-year-old rocks by geochemical and morphological traces, such as chemical compounds or structures that these organisms left behind. However, it is still not clear when and where life originated on Earth and when a diversity of species developed in these early microbial communities. Evidence is scarce and often disputed.

Now, researchers led by the University of Göttingen and Linnӕus University in Sweden have uncovered key findings about the earliest forms of life. In rock samples from South Africa, they found evidence dating to around 3.42 billion years ago of an unprecedentedly diverse carbon cycle involving various microorganisms. This research shows that complex microbial communities already existed in the ecosystems during the Palaeoarchaean period. The results were published in the journal Precambrian Research.

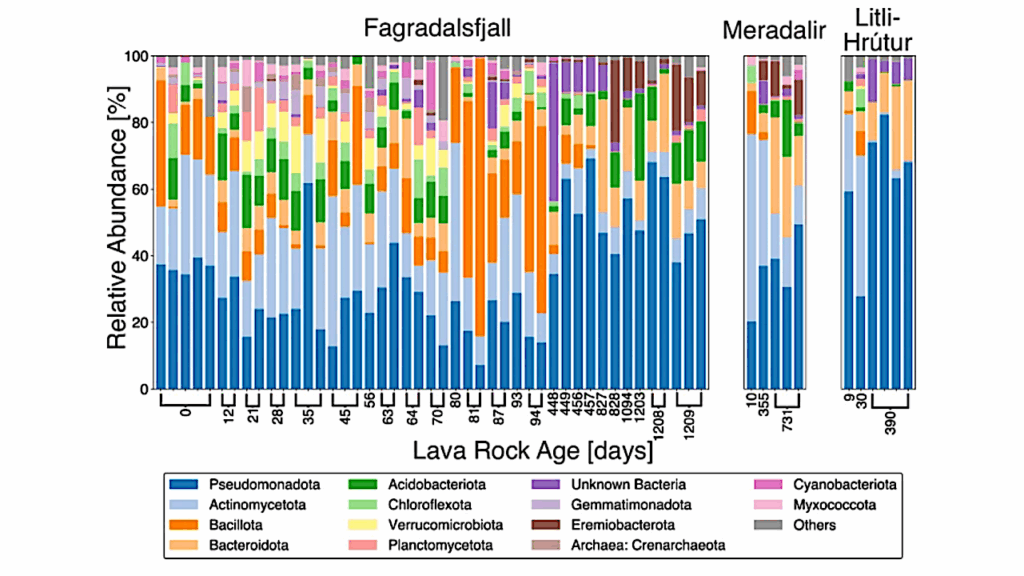

The researchers analysed well-preserved particles of carbonaceous matter – the altered remains of living organisms – and the corresponding rock layers from samples of the Barberton greenstone belt, a mountain range in South Africa whose rocks are among the oldest on the Earth’s surface. The scientists combined macro and micro analyses to clearly identify original biological traces and distinguish them from later contamination. They identified geochemical “fingerprints” of various microorganisms, including those that must have used sunlight for energy, metabolised sulphate and probably also produced methane.

The researchers determined the respective role of the microorganisms in the carbon cycle of the ecosystem at the time by combining geochemical data with findings on the texture of the rocks obtained from thin section analysis with a microscope. “By discovering carbonaceous matter in primary pyrite crystals and analysing carbon and sulphur isotopes in these materials, we were able to distinguish individual microbial metabolic processes,” explains the senior author of the study, Dr Henrik Drake from Linnӕus University.

First author Dr Manuel Reinhardt, from Göttingen University’s Geosciences Centre, adds: “We didn’t expect to find traces of so many microbial metabolic processes. It was like the proverbial search for a needle in a haystack.” The study provides a rare glimpse into the Earth’s early ecosystems. “Our findings significantly advance the understanding of ancient microbial ecosystems and open up new avenues for research in the field of palaeobiology.”

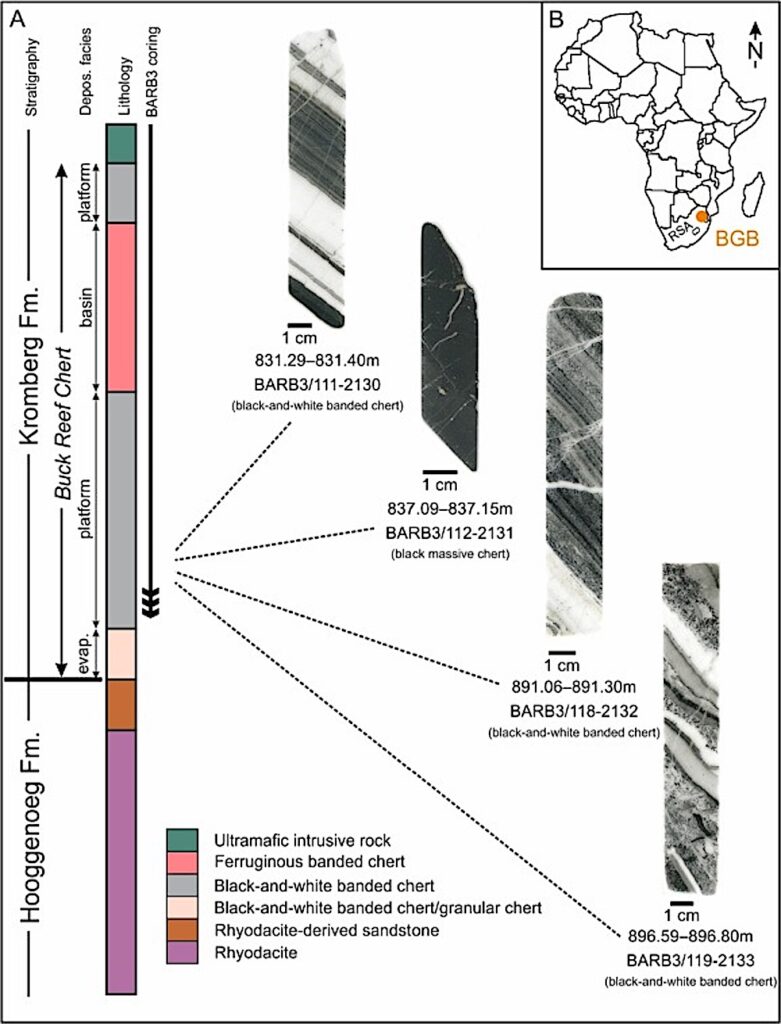

Sampling location and stratigraphy. A, Stratigraphic overview of the contact between the Hooggenoeg and Kromberg formations (modified after Greco et al., 2018). The Buck Reef Chert is a sedimentary sequence marking the base of the Kromberg Formation, and has a thickness of 250–400 m (Homann, 2019, Lowe and Fisher Worrell, 1999). The chert succession overlies volcanic rhyodacite and its erosion products, and is capped by an ultramafic sill (Hofmann et al., 2013b). The BARB3 drill core reaches into the lowermost part of the lower platform facies. The four cherts investigated were sampled from an interval of ca. 66 m, between 831 and 897 m depth. B, Map showing the location of the Barberton greenstone belt (BGB) in the northeast of the Republic of South Africa (RSA).

Reinhardt, M. et al. Aspects of the biological carbon cycle in a ca. 3.42-billion-year-old marine ecosystem. Precambrian Research (2024). DOI: 10.1016/j.precamres.2024.107289 (open access)

Astrobiology