Extreme Habitats: Microbial Life In Old Faithful Geyser

An eruption of Old Faithful Geyser in Yellowstone National Park is a sight to behold. Indeed, millions of tourists flock to the park each year to see it. Hot water and steam are ejected in the air to a height of 100–180 feet approximately every 90 minutes. Many adjectives come to mind to describe it: powerful, mesmerizing, unique, otherworldly . . . homey? Not so much.

Yet new research by Lisa M. Keller, published on PNAS Nexus earlier this year and to be presented on Sunday at the Geological Society of America’s GSA Connects 2023 meeting, shows that for some microbial life forms, Old Faithful Geyser is exactly that: home.

Thermus aquaticus — Food Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

Meet Thermocrinis ruber and Thermus aquaticus. Thermocrinis ruber is the most abundant bacterium residing in Old Faithful, making up over 60% of the microbial population. As a chemoautotroph, it makes its own energy, not only for its own sustenance, but also to the benefit of the rest of the microbial community. But how? Old Faithful is a dark, hot place, which makes photosynthesis impossible. Instead, Thermocrinis ruber takes CO2 outgassing from the geyser and turns it into carbon forms that are potentially cross-feeding heterotrophs in the community, such as Thermus aquaticus.

Both bacteria are extremophiles—life forms that thrive where most would not survive. Whatever the challenging environmental factor, there are microbes adapted to overcome it. Hypersaline pools? Check. Lack of oxygen? You bet. Scorching hot water? Not a problem.

Eruption of Old Faithful geyser taken between sampling trips. CREDIT Lisa M. Keller

Geysers present a unique challenge: they are extremely dynamic environments. As if being thrown hundreds of feet in the air every 90 minutes isn’t disruptive enough, the microbes are subject to fluctuating steam and water temperatures that constantly change throughout the eruption cycle.

In every challenge there is an opportunity, and Old Faithful’s thermal excursions and eruptions are no exception. More strains of Thermocrinis are found in Old Faithful than in any other non-geysing hot spring in Yellowstone. “We think that the highly dynamic geyser environment creates many different ecological niches that Thermocrinis can occupy, causing increased sub-species level diversity,” says Keller. These findings show not only that Old Faithful Geyser is habitable, but also that its dynamic environment promotes genomic diversity.

Image of the conduit of Old Faithful geyser where steam is rising up (left of picture) and splash pool sampled during this study immediately to the right of the opening. Tubing can be seen extending from where we were sampling in the splash pool. Permit number #5544. CREDIT Lisa M. Keller

In order to prevent any possible sample contamination, Keller collected geysed water as it was falling from the eruption in weighted sterile bins. Ten minutes after the end of the eruption she would walk out to the cone with a National Park Service escort and retrieve the precious samples. Additionally, she sampled a pool fed exclusively through Old Faithful’s eruptions.

Filtering mechanism used to pump water from the splash pool for analysis of microbial communities within the pool. Old Faithful geyser cone can be seen directly behind the filtration setup. Permit number #5544. CREDIT Lisa M. Keller

Plastic catch tub with weights used to collect plume water during Old Faithful eruption. Permit number #5544. CREDIT Lisa M. Keller

Once back in the laboratory, Keller incubated the samples at different temperatures representative of geyser and pool conditions. The objective? Monitor the microbial activity to verify that the sampled bacteria would really be active at those extreme temperatures. And active they were, to Keller’s delight. “They immediately showed signs of activity, suggesting there is active microbial life in Old Faithful waters!” says Keller.

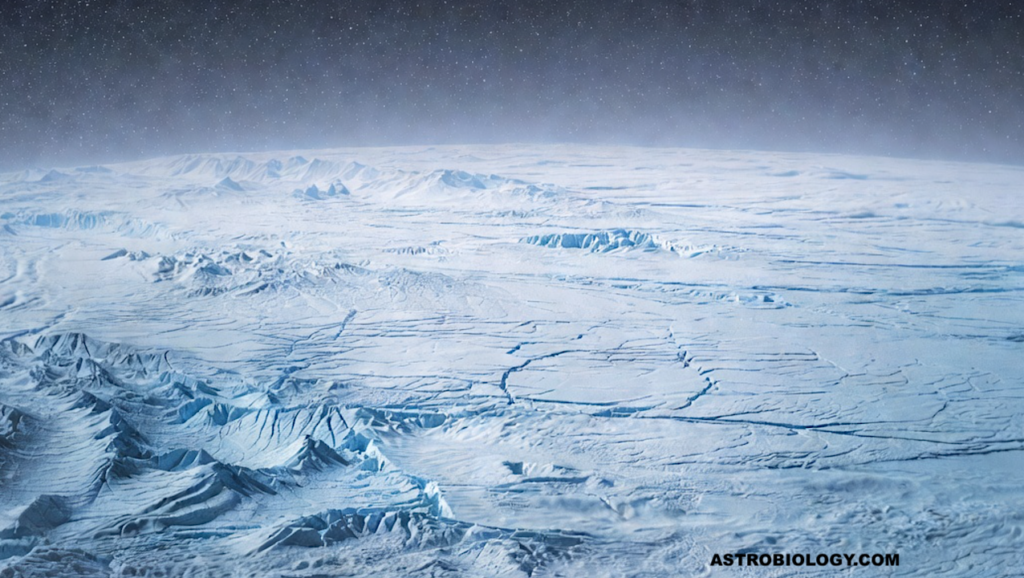

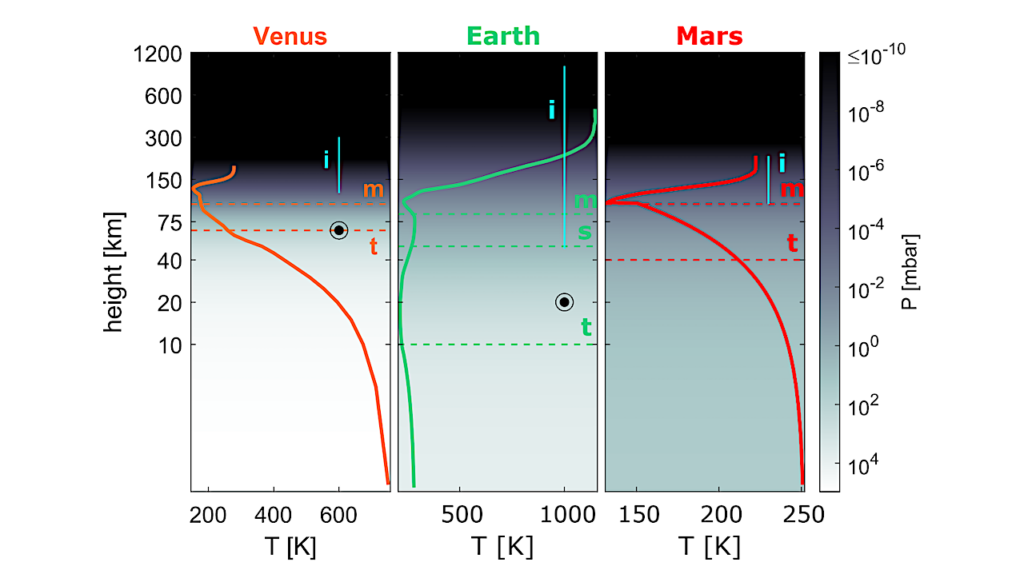

Beyond Earth, geysers are of extreme interest to the planetary community, as active geyser eruptions have been observed on the moons Enceladus and Europa. “Everybody gets excited about sampling Enceladus plumes,” says Keller, “but prior to this work we didn’t even have terrestrial geysers microbial samples. I thought, let’s take a step back and figure it out on our own planet first.” Sampling planetary geysers may still be a long way off, as the current methodology requires filtering liters and liters of water—something that would certainly be challenging away from Earth—but now that we know for sure that terrestrial geysers can host life, the race to find it on planetary geysers is on too.

An Active Microbiome in Old Faithful Geyser

Author: Lisa M. Keller, Montana State University, [email protected]

https://gsa.confex.com/gsa/2023AM/meetingapp.cgi/Paper/390179

Sunday, 15 October 2023, 8:05–8:25 a.m.

The Geological Society of America (https://www.geosociety.org) unites a diverse community of geoscientists in a common purpose to study the mysteries of our planet (and beyond) and share scientific findings. Members and friends around the world, from academia, government, and industry, participate in GSA meetings, publications, and programs at all career levels, to foster professional excellence. GSA values and supports inclusion through cooperative research, public dialogue on earth issues, science education, and the application of geoscience in the service of humankind.

Astrobiology