NASA's Search for Life: Astrobiology in the Solar System and Beyond

Are we alone in the universe? So far, the only life we know of is right here on Earth. But here at NASA, we’re looking.

NASA is exploring the solar system and beyond to help us answer fundamental questions about life beyond our home planet. From studying the habitability of Mars, probing promising “oceans worlds,” such as Titan and Europa, to identifying Earth-size planets around distant stars, our science missions are working together with a goal to find unmistakable signs of life beyond Earth (a field of science called astrobiology).

Through the study of astrobiology, NASA invests in understanding the origins, evolution, and limits of life on Earth. This work has been important in shaping ideas about where to focus search for life efforts. As NASA explores the solar system, our understanding of life on Earth and the potential for life on other worlds has changed alongside the many discoveries. The study of organisms in extreme environments on Earth, from the polar plateau of Antarctica to the depths of the ocean, have highlighted that life as we know it is highly adaptable, but not always easy to find. The search for life requires great care, and is based in the knowledge we gain by studying life on Earth through the lens of astrobiology. If there’s something out there, we may not yet know how to recognize it.

Dive into the past, present, and future of NASA’s search for life in the universe.

Past Missions

Viking 1 and 2

Over 45 years ago, the Viking Project found a place in history when it became the first U.S. mission to land a spacecraft safely on the surface of Mars.

Viking 1 and 2, each consisting of an orbiter and a lander, were NASA’s first attempt to search for life on another planet and thus the first mission dedicated to astrobiology. The mission’s biology experiments revealed unexpected chemical activity in the Martian soil, but provided no clear evidence for the presence of living microorganisms near the landing sites.

Galileo

NASA’s Galileo mission orbited Jupiter for almost eight years, and made close passes by all its major moons. Galileo returned data that continues to shape astrobiology science – particularly the discovery that Jupiter’s icy moon Europa has evidence of a subsurface ocean with more water than the total amount of liquid water found on Earth. These findings also expanded the search for habitable environments outside of the traditional “habitable zone” of a system, the distance from a star at which liquid water can persist on the surface of a planet.

Cassini

For more than a decade, the Cassini spacecraft shared the wonders of Saturn and its family of icy moons – taking us to astonishing worlds and expanding our understanding of the kinds of worlds where life might exist.

For the first time, astrobiologists were able to see through the thick atmosphere of Titan and study the moon’s surface, where they found lakes and seas filled with liquid hydrocarbons. Astrobiologists are studying what these liquid hydrocarbons could mean for life’s potential on Titan. Cassini also witnessed icy plumes erupting from Saturn’s small moon Enceladus. When flying through the plumes, the spacecraft found evidence of saltwater and organic chemicals. This raised questions about whether habitable environments could exist beneath the surface of Enceladus.

Spirit and Opportunity Mars Exploration Rovers

NASA’s twin Mars Exploration Rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, launched towards Mars in 2003 in search of answers about the history of water on Mars. Originally a three-month prime mission, both robotic explorers far outlasted their original missions and spent years collecting data at the surface of Mars.

Spirit and Opportunity were the first mission to prove liquid water, a key ingredient for life, had once flowed across the surface of Mars. Their findings shaped our understanding of Mars’ geology and past environments, and importantly suggested Mars’ ancient environments may once have been suitable for life.

Kepler and K2

NASA’s first planet-hunting mission, the Kepler Space Telescope, paved the way for our search for life in the solar system and beyond. An important part of Kepler’s work was the identification of Earth-size planets around distant stars.

After nine years in deep space, collecting data that indicate our sky to be filled with billions of hidden planets – more planets even than stars – the space telescope retired in 2018. Kepler left a legacy of more than 2,600 exoplanet discoveries, many of which could be promising places for life.

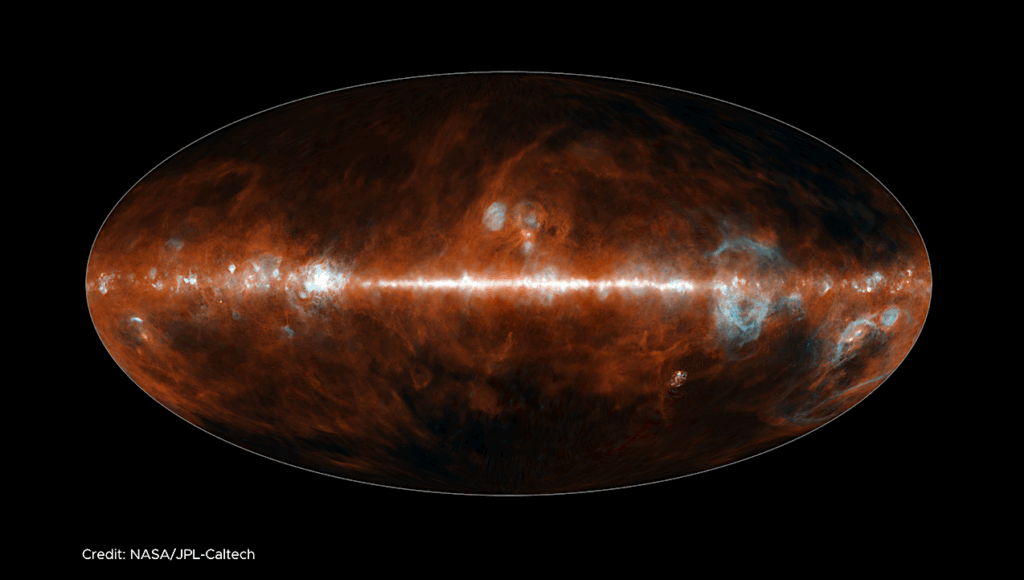

Spitzer

Over its sixteen years in space, the Spitzer Space Telescope evolved into a premier tool for studying exoplanets, using its infrared view of the universe. Spitzer marked a new age in planetary science as one of the first telescopes to directly detect light from the atmospheres of planets outside the solar system, or exoplanets. This enabled scientists to study the composition of those atmospheres and even learn about the weather on these distant worlds.

Spitzer’s infrared instruments allowed scientists to peer into cosmic regions that are hidden from optical telescopes, including dusty stellar nurseries, the centers of galaxies, and newly forming planetary systems. Spitzer’s infrared eyes also enabled astronomers to see cooler objects in space, like failed stars (brown dwarfs), extrasolar planets, giant molecular clouds, and organic molecules that may hold the secret to life on other planets.

Current Missions

Hubble

Since it launched in 1990, the Hubble Space Telescope has made immense contributions to astrobiology. Astronomers used Hubble to make the first measurements of the atmospheric composition of extrasolar planets, and Hubble is now vigorously characterizing exoplanet atmospheres with constituents such as sodium, hydrogen, and water vapor. Hubble observations are also providing clues about how planets form, through studies of dust and debris disks around young stars.

Not all of Hubble’s contributions involve distant targets. Hubble has also been used to study bodies within the solar system, including asteroids, comets, planets, and moons, such as the intriguing ocean-bearing icy moons Europa and Ganymede. Hubble has provided invaluable insight into life’s potential in the solar system and beyond.

MAVEN

NASA’s atmosphere-sniffing Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission launched in November 2013 and began orbiting Mars roughly a year later. Since that time, the mission has made fundamental contributions to understanding the history of the Martian atmosphere and climate.

Astrobiologists are working with this atmospheric data to better understand how and when Mars lost its water and identifying periods in Mars’ history when habitable environments were most likely to exist at the planet’s surface.

Mars Odyssey

For two decades, NASA’s Mars Odyssey - the longest-lived spacecraft at the Red Planet – has helped locate ice, assess landing sites, and study the planet’s mysterious moons.

Odyssey has provided global maps of chemical elements and minerals that make up the surface of Mars. These detailed maps are used by astrobiologists to determine the evolution of the Martian environment and its potential for life.

Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) is on a search for evidence

that water persisted on the surface of Mars for a long period of time. While other Mars missions have shown that water flowed across the surface in Mars’ history, it remains a mystery whether water was ever around long enough to provide a habitat for life.

Data from MRO is essential to astrobiologists studying the potential for habitable environments on past and present Mars. Additionally, these studies are important in building climate models for Mars, and for use in comparative planetology studies for the potential habitability of exoplanets that orbit distant stars.

Curiosity Mars Rover

The Curiosity Mars rover is studying whether Mars ever had environments capable of supporting microbial life. In other words, its mission is to determine whether the planet had all of the ingredients life needs – such as water, carbon, and a source of energy – by studying its climate and geology.

It’s been nearly nine years since Curiosity touched down on Mars in 2012, and the robot geologist keeps making new discoveries. Curiosity provided evidence that freshwater lakes filled Gale Grater billions of years ago. Lakes and groundwater persisted for millions of years and contained all the key elements necessary for life, demonstrating Mars was once habitable.

TESS Mission

The Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) is the next step in the search for planets outside of our solar system, including those that could support life. Launched in 2018, TESS is on a mission to survey the entire sky and is expected to discover and catalogue thousands of exoplanets around nearby bright stars.

To date, TESS has discovered more than 120 confirmed exoplanets and more than 2,600 planet candidates. The planet-hunter will continue to find exoplanets targets that NASA’s upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will study in further detail.

Perseverance Mars Rover

NASA’s newest robot astrobiologist, the Perseverance Mars rover, touched down safely on Mars on February 18, 2021, and is kicking off a new era of exploration on the Red Planet. Perseverance will search for signs of ancient microbial life, which will advance the agency’s quest to explore the past habitability of Mars.

What really sets this mission apart is that the rover has a drill to collect core samples of Martian rock and soil, and will store them in sealed tubes for pickup by a future Mars Sample Return mission that would ferry them back to Earth for detailed analysis.

Upcoming Missions

James Webb Space Telescope

The James Webb Space Telescope (Webb), slated to launch in 2021, will be the premier space-based observatory of the next decade. Webb is a large infrared telescope with a 6.5-meter primary mirror.

Webb observations will be used to study every phase in the history of the universe, including planets and moons in our solar system, and the formation of distant solar systems potentially capable of supporting life on Earth-like exoplanets. The Webb telescope will also be capable of making detailed observations of the atmospheres of planets orbiting other stars, to search for the building blocks of life on Earth-like planets beyond our solar system.

Europa Clipper Mission

Jupiter’s moon Europa may have the potential to harbor life. The Europa Clipper mission will conduct detailed reconnaissance of Europa and investigate whether the icy moon could harbor conditions suitable for life. Targeting a 2024 launch, the mission will place a spacecraft in orbit around Jupiter in order to perform a detailed investigation of Europa — a world that shows strong evidence for an ocean of liquid water beneath its icy crust.

Europa Clipper is not a life-detection mission, though it will investigate whether the icy moon, with its subsurface ocean, has the capability to support life. Understanding Europa’s habitability will help scientists better understand how life developed on Earth and the potential for finding life beyond our planet.

Dragonfly Mission to Titan

The Dragonfly mission will deliver a rotorcraft to visit Saturn’s largest and richly organic moon, Titan. Slated for launch in 2027 and arrival in 2034, Dragonfly will sample and examine dozens of promising sites around Saturn’s icy moon and advance our search for the building blocks of life.

This revolutionary mission will explore diverse locations to look for prebiotic chemical processes common on both Titan and Earth. Titan is an analog to the very early Earth, and can provide clues to how prebiotic chemistry under these conditions may have progressed.

Nancy Grace Roman Telescope

Slated to launch in the mid-2020s, the Roman Space Telescope will have a field of view that is 200 times greater than the Hubble infrared instrument, capturing more of the sky with less observing time. In addition to ground-breaking astrophysics and cosmology, the primary instrument on Roman, the Wide Field Instrument, has a rich menu of exoplanet science. It will perform a microlensing survey of the inner Milky Way that will reveal thousands of worlds orbiting within the habitable zone of their star and farther out, while providing an additional bounty of more than 100,000 transiting exoplanets.

The mission will also be fitted with “starglasses,” a coronagraph instrument that can block out the glare from a star and allow astronomers to directly image giant planets in orbit around it. The coronagraph will provide the first in-space demonstration of technologies needed for future missions to image and characterize smaller, rocky planets in the habitable zones of nearby stars. Roman coronagraph will make observations that could contribute to the discovery of new worlds beyond our solar system and advance the study of extrasolar planets that could be suitable for life.

Learn more about the NASA Astrobiology Program: https://astrobiology.nasa.gov/