Deep Water On Neptune And Uranus May Be Magnesium-rich

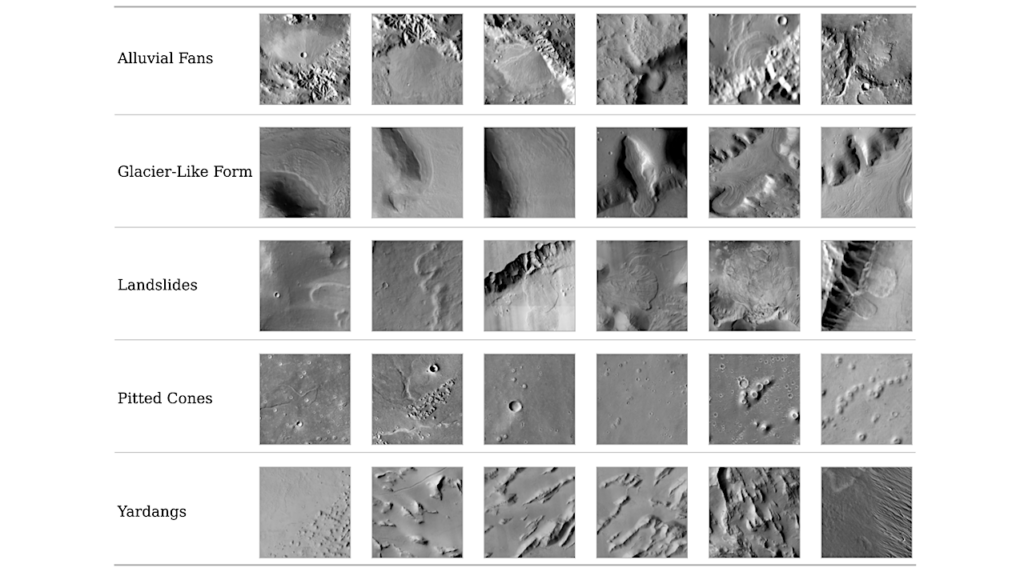

While scientists have amassed considerable knowledge of the rocky planets in our solar system, like Earth and Mars, much less is known about the icy water-rich planets, Neptune and Uranus.

In a new study (Atomic-scale mixing between MgO and H2O in the deep interiors of water-rich planets) recently published in Nature Astronomy, a team of scientists recreated the temperature and pressure of the interiors of Neptune and Uranus in the lab, and in so doing have gained a greater understanding of the chemistry of these planets’ deep water layers. Their findings also provide clues to the composition of oceans on water-rich exoplanets outside our solar system.

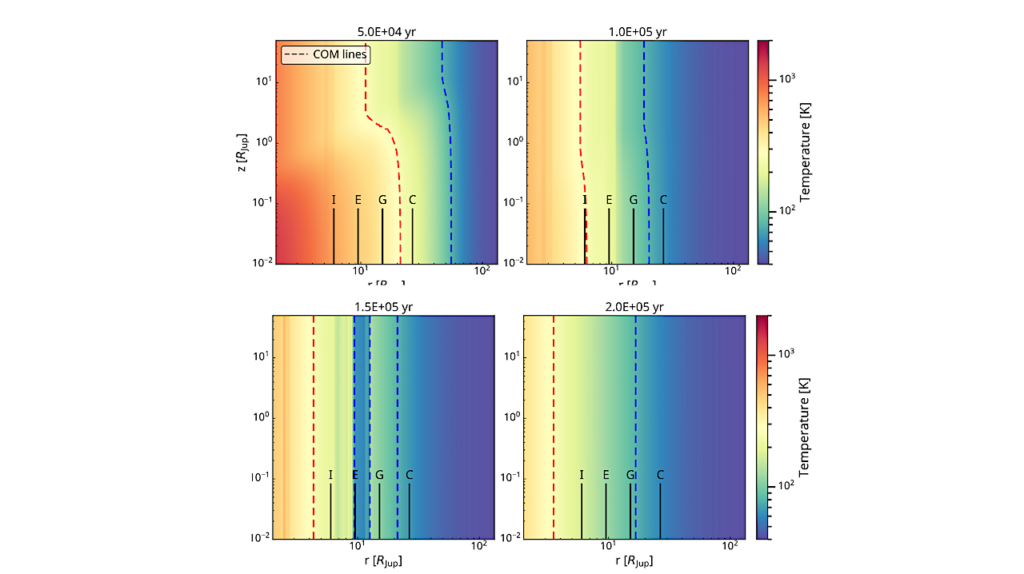

Neptune and Uranus are conventionally thought to have distinct separate layers, consisting of an atmosphere, ice or fluid, a rocky mantle and a metallic core. For this study, the research team was particularly interested in possible reaction between water and rock in the deep interiors.

“Through this study, we were seeking to extend our knowledge of the deep interior of ice giants and determine what water-rock interactions at extreme conditions might exist,” says lead author Taehyun Kim, of Yonsei University in South Korea. “Ice giants and some exoplanets have very deep water layers, unlike terrestrial planets. We proposed the possibility of an atomic-scale mixing of two of the planet-building materials (water and rock) in the interiors of ice giants.”

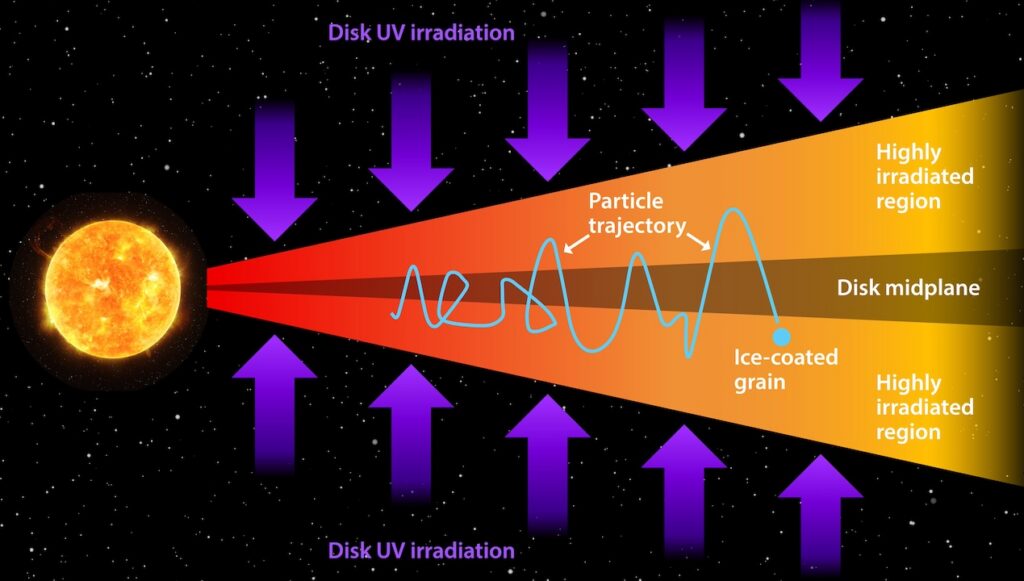

To mimic the conditions of the deep water layers on Neptune and Uranus in the lab, the team first immersed typical rock-forming minerals, olivine and ferropericlase, in water and compressed the sample in a diamond-anvil to very high pressures. Then, to monitor the reaction between the minerals and water, they took X-ray measurements while a laser heated the sample to a high temperature.

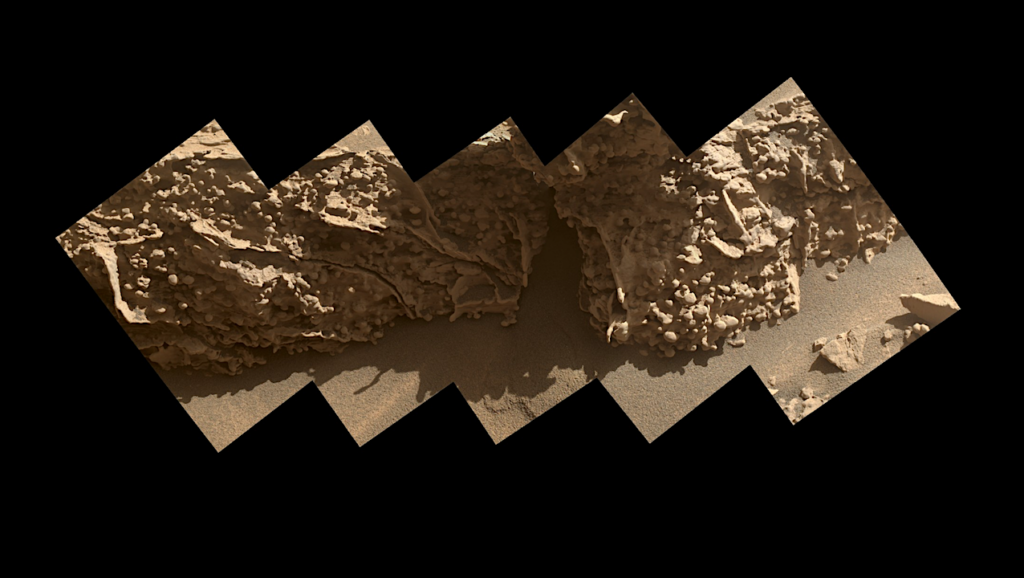

An electron microscopy image of the olivine sample shows a large empty dome structure where magnesium under high-pressure water precipitated as magnesium oxide. Credit: Kim et al.

The resulting chemical reaction led to high concentrations of magnesium in the water. Based on these findings, the team concluded that oceans on water-rich planets may not have the same chemical properties as the Earth’s ocean and high pressure would make those oceans rich in magnesium.

“We found that magnesium becomes much more soluble in water at high pressures. In fact, magnesium may become as soluble in the water layers of Uranus and Neptune as salt is in Earth’s ocean,” says study co-author Sang-Heon Dan Shim of Arizona State University’s School of Earth and Space Exploration.

These characteristics may also help solve the mystery of why Uranus’ atmosphere is much colder than Neptune’s, even though they are both water-rich planets. If much more magnesium exists in the Uranus’ water layer below the atmosphere, it could block heat from escaping from the interior to the atmosphere.

“This magnesium-rich water may act like a thermal blanket for the interior of the planet,” says Shim.

Beyond our solar system, these high-pressure and high-temperature experiments may also help scientists gain a greater understanding of sub-Neptune exoplanets, which are planets outside of our solar system with a smaller radius or a smaller mass than Neptune.

Sub-Neptune planets are the most common type of exoplanets that we know of so far, and scientists studying these planets hypothesize that many of them may have a thick water-rich layer with a rocky interior. This new study suggests that the deep oceans of these exoplanets would be much different from Earth’s ocean and may be magnesium-rich.

“If an early dynamic process enabled a rock-water reaction in these exoplanets, the topmost water layer may be rich in magnesium, possibly affecting the thermal history of the planet,” says Shim.

For next steps, the team hopes to continue their high-pressure/high-temperature experiments under diverse conditions to learn more about the composition of planets.

“This experiment provided us with a plan for further exploration of the unknown phenomena in ice giants,” says Kim.

Additional authors of this study include Stella Chariton and Vitali Prakapenka of the University of Chicago; Anna Pakhomova and Hanns-Peter Liermann of the Deutsches Elektronen Synchrotron, Germany; Zhenxian Liu of the University of Illinois, Chicago; Sergio Speziale of the German Research Center for Geosciences, Germany; and Yongjae Lee of Yonsei University, South Korea.

About Arizona State University

Arizona State University has developed a new model for the American Research University, creating an institution that is committed to access, excellence and impact. ASU measures itself by those it includes, not by those it excludes. As the prototype for a New American University, ASU pursues research that contributes to the public good, and ASU assumes major responsibility for the economic, social and cultural vitality of the communities that surround it.

Astrobiology