A Super-Earth Is Discovered Which Can Be Used To Test Planetary Atmosphere Models

During the past 25 years astronomers have discovered a wide variety of exoplanets, made of rock, ice and gas, thanks to the construction of astronomical instruments designed specifically for planet searches.

Also, using a combination of different observing techniques they have been able to determine a large numher of masses, sizes, and hence densities of the planets, which helps them to estimate their internal composition and raising the number of planets which have been discovered outside the Solar System.

However, to study the atmospheres of the rocky planets, which would made it possible to characterize fully those exoplanets which are similar to Earth, is extremely difficult with currently available instruments. For that reason, the atmospheric models for rocky planets are still not tested.

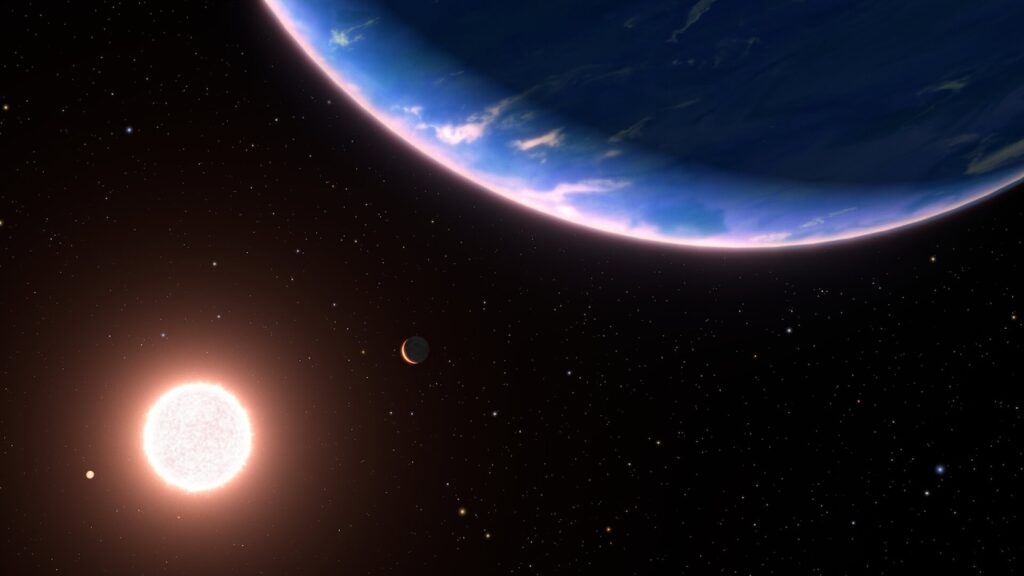

So it is interesting that the astronomers in the CARMENES (Calar Alto high- Resolution search for M dwarfs with Exoearths with Near-infrared and optical échelle Spectrographs), consortium in which the Instituto de Astrofisica de Canarias (IAC) is a partner, have recently published a study, led by Trifon Trifonov, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy at Heidelberg (Germany), about the discovery of a hot super-Earth in orbit around a nearby red dwarf star Gliese 486, only 26 light years from the Sun.

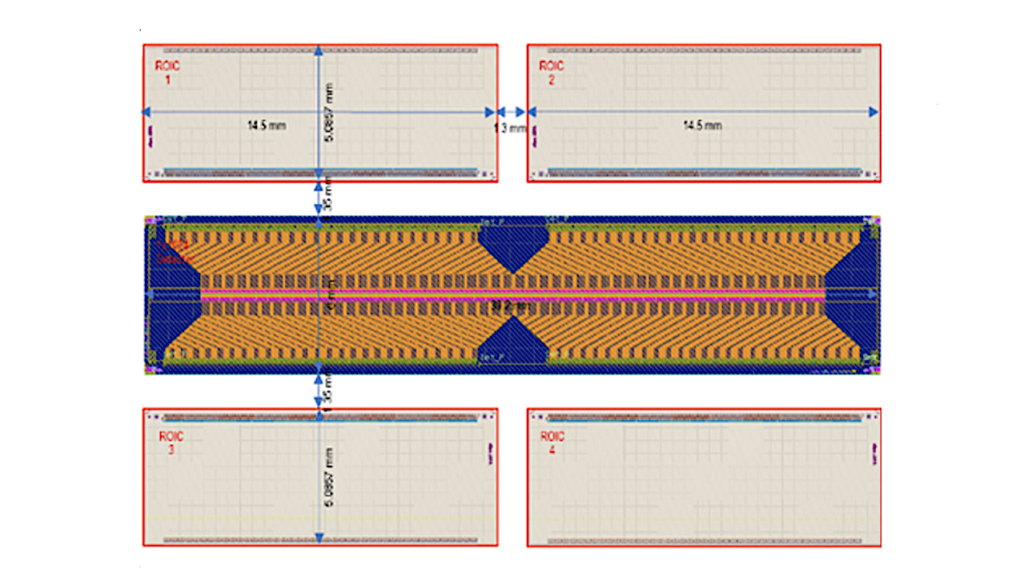

To do this the scientists used the combined techniques of transit photometry and radial velocity spectroscopy, and used, among others, observations with the instrument MuSCAT2 (Multicolour Simultaneous Camera for studying Atmospheres of Transiting exoplanets) on the 1.52m Carlos Sánchez Telescope at the Teide Observatory. The results of this study have been published in the journal Science.

The planet they discovered, named Gliese 486b, has a mass 2.8 times that of the Earth, and is only 30% bigger. “Calculating its mean density from the measurements of its mass and radius we infer that its composition is similar to that of Venus or the Earth, which have metallic nuclei inside them”, explains Enric Pallé, an IAC researcher and a co-author of the article.

Gliese 486b orbits its host star on a circular path every 1.5 days, at a distance of 2.5 million kilometres. In spite of being so near to its star, the planet has probably conserved part of its original atmosphere (the star is much cooler than our Sun) so that it is a good candidate to observe in more detail with the next generation of space and ground telescopes.

For Trifonov, “the fact that this planet is so near the sun is exciting because it will be possible to study it in more detail using powerful telescopes such as the iminent James Webb Space Telescope and the ELT (Extremely Large Telescope) now being built”.

Gliese 486b takes the same length of time to spin on its axis as to orbit its host star, so that it always has the same side facing the star. Although Gliese 486 is much fainter and cooler than the Sun, the radiation is so intense that the surface of the planet heats up to at least 700K (some 430 degrees C). Because of this, the suface of Gliese 486b is probably more like the surface of Venus that that of the Earth, with a hot dry landscape, with burning rivers of lava. However, unlike Venus, Gliese 486b may have a thin atmosphere.

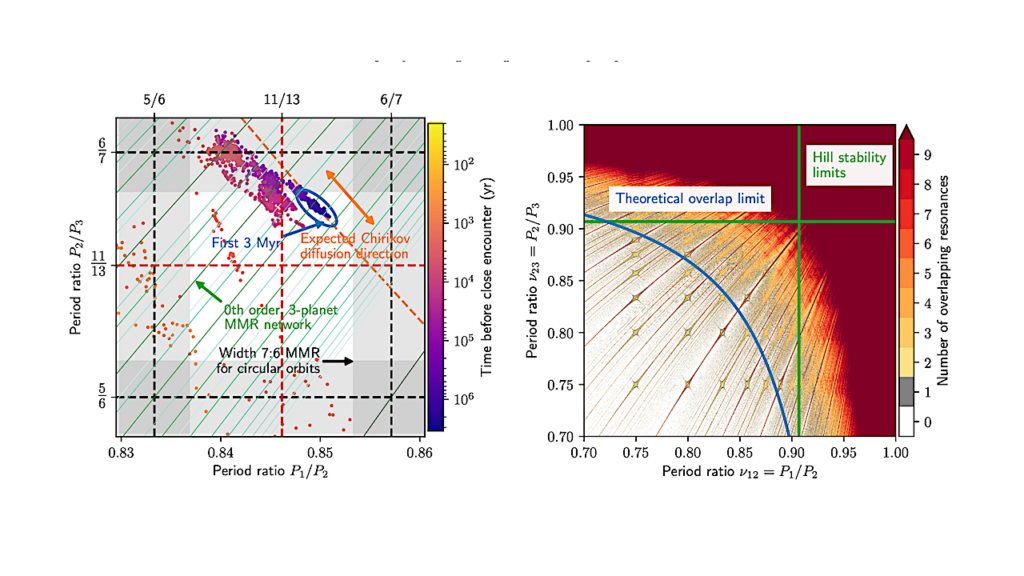

Calculations made with existing models of planetary atmospheres can be consistent with both hot surface and thin atmosphere scenarios because stellar irradiation tends to evaporate the atmosphere, while the planet’s gravity tends to hold it back. Determining the balance between the two contributions is difficult today.

“The discovery of Gliese 486b has been a stroke of luck. If it had been around a hundred degrees hotter all its surface would be lava, and its atmosphere would be vaporized rock”, explains José Antonio Caballero, a researcher at the Astrobiology Centre (CAB, CSIC-INTA) and co-author of the article. “On the other hand, if Gliese 486b had been around a hundred degrees cooler, it would not have been suitable for the follow-up observations”.

Future planned observations by the CARMENES team will try to determine its orbital inclination, which makes it possible for Gliese 486b to cross the line of sight between us and the surface of the star, oculting some of its light, and producing what are known as transits.

They will also make spectroscopic measurements, using “emission spectroscopy”, when the areas of the hemisphere lit up by the star are visible as phases of the planet (analagous to the phases of our Moon), during the orbits of Gliese 486b, befor it disappears behind the star. The spectrum observed will contain information about the conditions on the illuminated hot surface of the planet.

“We can’t wait until the new telescopes are available”, admits Trifonov. “The results we may obtain with them will help us to get a better understanding of the atmospheres of rocky planets, their extensión, their very high density, their composition, and their influence in distributing energy around the planets.

The CARMENES project, whose consortium is made up by 11 research institutions in Spain and Germany, has the aim of monitoring a set of 350 red dwarf stars to seek planets like the Earth, using a spectrograph on the 3.5 m telescope at the Calar Alto Observatory (Spain). The present study has also used spectroscopic measurements to infer the mass of Gliese 486b. Observations were made with the MAROON-X instrument on Gemini North (8.1m) in the USA, and archive data were taken from the Keck 10 m telescope (USA) and the 3.6m telescope of ESO, (Chile).

The photometric observations come from NASA’s TESS (Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite) space observatory, (USA), whose data were basic for obtaining the radius of the planet, from the MuSCAT2 instrument on the 1.52m Carlos Sánchez Telescope at the Teide Observatory (Spain) and from the LCOGT (Las Cumbres Observational Global Telescope) in Chile, among others.

Astrobiology