Exploring Hot Deep-Sea Vents for Signs of Extreme Life

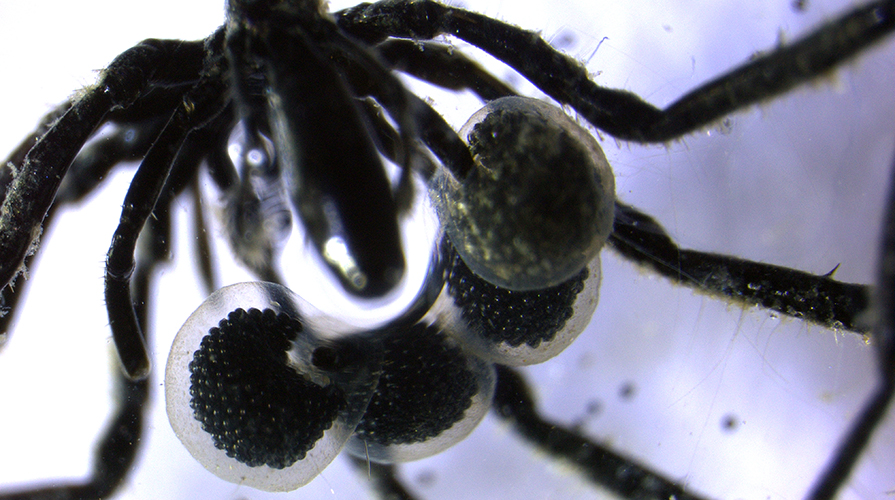

Microbiology professor Jim Holden, a researcher in the School of Earth and Sustainability, recently received a three-year, $441,219 grant from NASA’s Exobiology Program to study competition between different types of thermophilic, or heat-loving, microbes that live in deep-sea volcanoes called hydrothermal vents.

The program’s goal is to “understand the origin, evolution, distribution and future of life in the universe. Research is centered on the origin and early evolution of life, the potential of life to adapt to different environments, and the implications for life elsewhere,” NASA says.

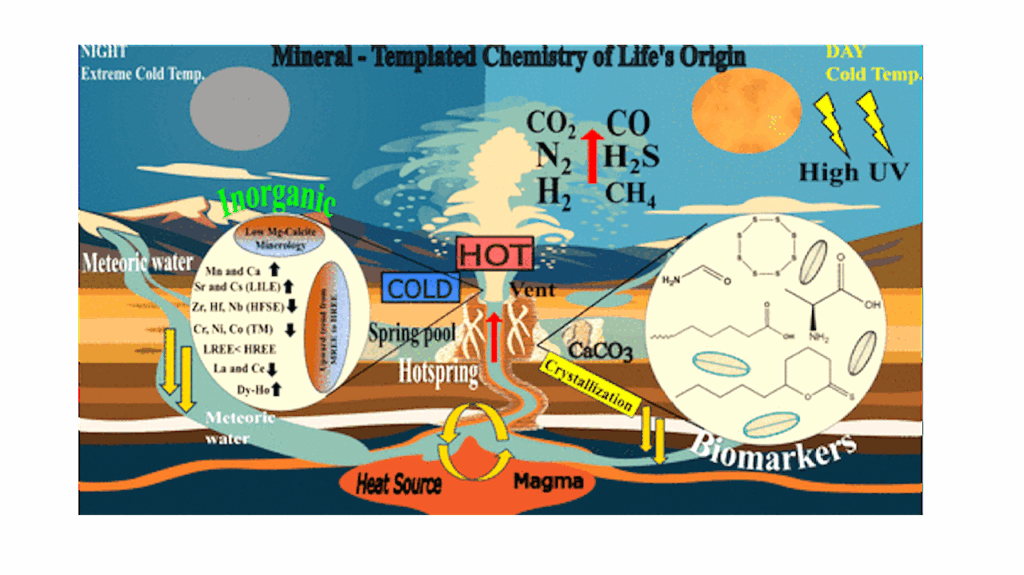

Holden, an expert in high-temperature microbes, adds that the investigation will estimate the population size, composition and impact of different types of thermophilic life in the underwater vents, where there is no oxygen or sunlight. These organisms live at very high temperatures and feed on hydrogen, carbon dioxide, sulfur and iron from the vents.

He explains, “This life is thought to be representative of early life on Earth, and hydrothermal vents are thought to be like habitats on Mars and the moons of Jupiter and Saturn, where there may be evidence of past or even present microbial life.”

Different kinds of life use different kinds of chemical reactions to make energy for themselves, the microbiologist points out. In general, scientists believe that the organism that have the most favorable chemical reaction in an environment will do better than the other organisms present. Holden says, “The question is, how can two environments that are chemically similar have different kinds of microbes living in them?”

Two years ago, Holden and mineralogist Darby Dyar at Mount Holyoke College received a $630,000 grant from the NASA program to develop techniques to detect and distinguish the different types of microbial life using remote sensing. Those instruments are already on the Mars rovers and will likely be used on future missions to Mars and elsewhere, Holden says.

Eventually, NASA will use findings from these and studies by others to create a microbial library so that rovers crawling on Mars or swimming in the seas of Saturn or Jupiter’s moons can recognize what they are encountering. The current study will explore whether there may be other important factors involved when considering competition between different kinds of life, Holden notes. Results of this study will be useful for NASA, he says, “to predict where they might find life and how to interpret the results that we receive from rovers, landers and satellites that are visiting or will visit other planets and moons.”

Results also should help researchers to interpret how life operates in past and modern earth environments, which can be useful for understanding chemical changes in the environment, for oil and gas recovery, and for the application of these organisms for removing pollution and generating bioenergy, he notes.

Astrobiology