Glacier Algae Creates Dark Zone At The Margins Of The Greenland Ice Sheet

New research led by scientists from the University of Bristol has revealed new insights into how the microscopic algae that thrives along the edge of the Greenland Ice Sheet causes widespread darkening.

This darkening is critically important as darker ice absorbs more sunlight energy and melts faster, accelerating the overall melting of the ice, which is the single largest contributor to global sea level rises.

Extremophile microscopic algae, or so-called ‘glacier algae’, are able to live in the upper few centimetres of ice on the surfaces of glaciers and ice sheets and can form widespread blooms during the summer melt season.

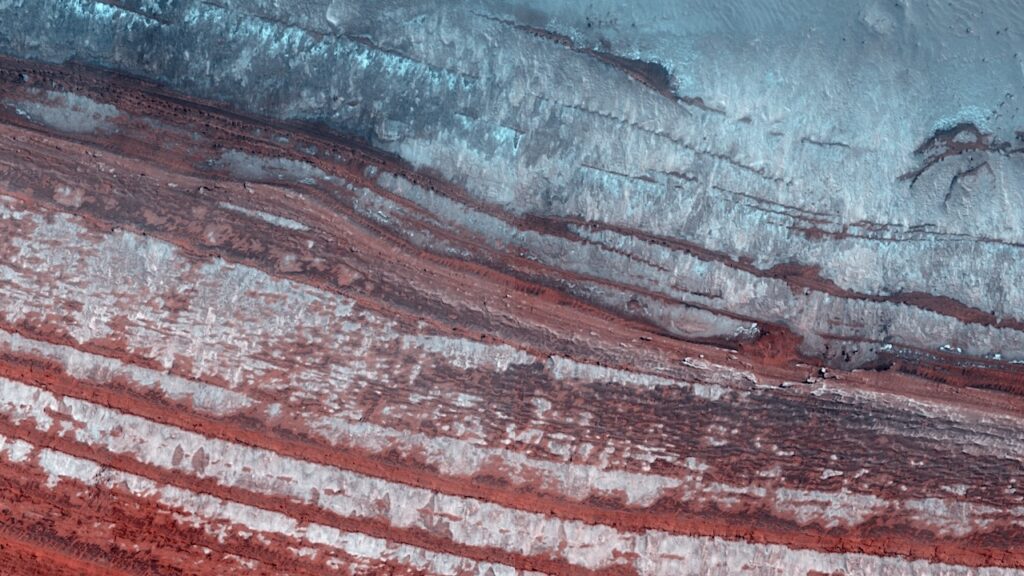

Glacier algal blooms on the Greenland Ice Sheet are so extensive that their presence in the surface ice is thought responsible for widespread darkening along the western margin of the ice sheet known as the ‘dark zone’ that has appeared in satellite observations over the last two decades.

The link between ice sheet darkening and glacier algal blooms had already been supported by modelling and field observations, but it is still unknow exactly how or why the algae causes widespread darkening.

Using detailed field observations, sampling, experimentation and modelling, the Bristol-led team, as part of the NERC-funded Black and Bloom Project, have demonstrated how glacier algae regulate energy within their cells in order to balance their requirements for photosynthesis and growth with the extreme light and temperature environment of the Greenland Ice Sheet and how they are optimised to darken and melt the ice.

The study, published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, reveals how glacier algae produce a unique phenolic ‘sunscreen’ pigment at 11-times the cellular content of chlorophyll-a (normally the most abundant pigment in green microalgae).

This phenolic pigment serves to capture and absorb most of the intense sunlight that the algae receive where they live on the surface of the ice sheet, protecting the algae’s chloroplasts, which are located underneath vacuoles filled with this pigment, from excessive UV and visible radiation.

The energy that is absorbed by this sunscreen pigment is subsequently available to the cell as heat for melt generation – an incredibly clever mechanism for algae that lives in an icy world, where access to liquid water is a major limitation on growth and survival.

This pigmentation protects cells from excessive sunlight, but also harnesses the energy for melt generation proximal to the cell, providing access to liquid water and dissolved nutrients critical for life.

Unfortunately, this heavy production of pigment is also one of the reasons why the Greenland Ice Sheet darkens so significantly during summer melt seasons, when glacier algae reach bloom abundances (around 10,000 cells per millilitre of melt water) in surface ice, driving an approximate ten percent increase in surface melt.

The study’s lead author, Dr Chris Williamson from the University of Bristol’s Bristol Glaciology Centre and School of Geographical Sciences, said: “Permanently cold ecosystems make up more than 70 percent of the Earth’s biosphere, though we know very little about the microorganisms that are able to thrive in these extreme environments.

“Our work has provided novel insight in the ecology and physiology of extremophile microalgae that live on the surfaces of glaciers and ice sheets, demonstrating how life is able to thrive within these extreme icy environments.

“This work has significant applied applications for studies of the mass balance (melt versus growth) of glacier and ice sheet systems, allowing the incorporation of such ‘biological-albedo’ effects into calculations of ice sheet surface reflectance (darkening) and melt.”

After quantifying the full suite of pigments produced by glacier algae and modelling their growth on the surface of the Greenland Ice Sheet surface, the team’s next step is to incorporate all of these ‘biological effects’ into larger models of Greenland ice sheet mass balance to predict their overall contribution to melt of the ice sheet and global sea level rise.

This next step necessitates a numerical modelling approach using large-scale regional climate models, given the size of the Greenland Ice Sheet. This work is currently underway as part of the Black and Bloom and Deep Purple projects.