Rotifer Studies In Space

With the spacewalk season on hold until next year, ESA astronaut Luca Parmitano took his time to prepare the orbital home for new, tiny and incredibly resistant passengers. Rotifers, commonly called wheel animals, are usually less than a millimetre in size and usually found in fresh water and moist soil.

These microorganisms arrived on Sunday on the 19th SpaceX Dragon supply mission, and Luca is hosting them inside Europe’s long running incubator in space, Kubik. The astronaut set the thermostast of their space cubicle at 15°C – the optimal temperature for growing these creatures in.

Biologists are interested to see how these curious animals handle stress and repair damage caused by radiation in microgravity. The results from the Rotifer-B study could lead to improved protection of professionals exposed to radiation in their work or cancer patients during radiation therapy.

Radiation Rotifer

Rotifers, commonly called wheel animals, can be found in almost all pools of water no matter how small including moist ground, moss and even on other animals. Most species are less than a millimetre in size and are fascinating to biologists as they are masters of survival.

A species of rotifers called bdelloids are exceptional as no male has ever been found, meaning they produce offspring from unfertilised eggs. Despite the genetic similarity they can survive for very long periods without water; rolling up into a pod they can survive year-long droughts in the Sahara desert as well as in the frozen plains of Antarctica. Simply add water and the bdelloids will uncurl and spring back to normal function.

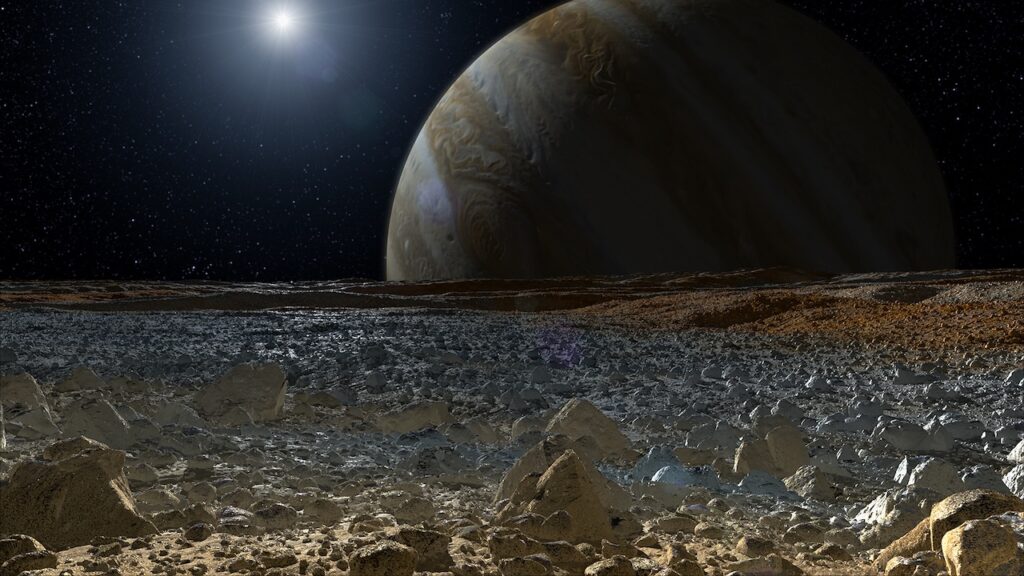

Bdelloids have another trick up their sleeve: they are extremely resistant to radiation. Understanding how they survive radiation levels that would kill many other organisms (and indeed ourselves) will gain insights into how we could improve spacecraft and protect astronauts against cosmic radiation. Earth’s atmosphere protects us from cosmic radiation but at 400 km altitude on the International Space Station astronauts already receive radiation doses 250 times higher than at sea level.

As humankind ventures farther to explore our Solar System on longer missions, finding ways to protect ourselves from radiation is key. The results from the Rotifer-B study could also lead to measures to improve protection of professionals who are exposed to radiation in their work or cancer patients during radiation therapy.

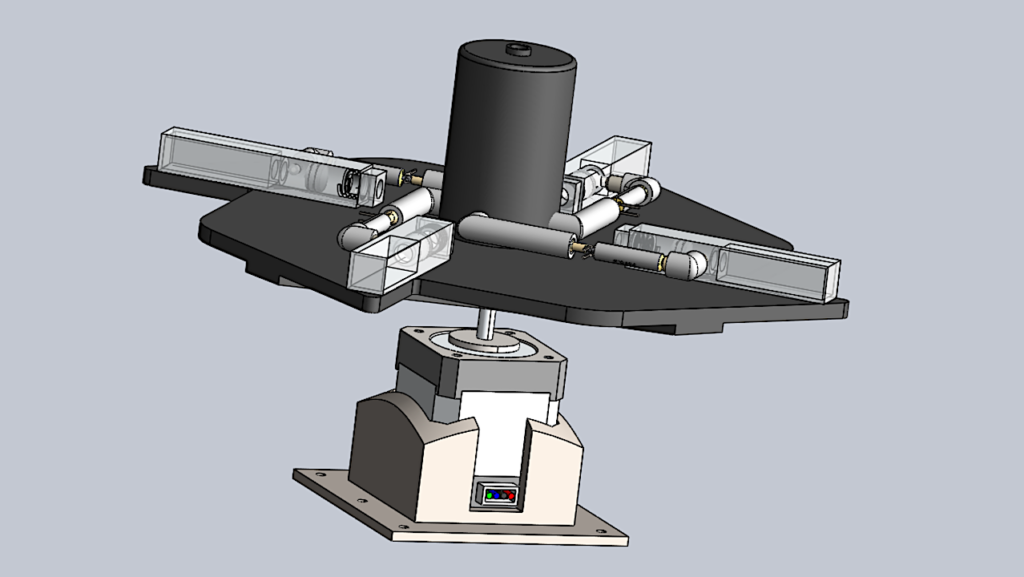

The experiment is split into two halves: one focuses explicitly on the effects of microgravity (Part 1) and the other on DNA damage and repair (Part 2). Part 1 will see culture bags of fresh rotifers with a meal of lettuce juice and water launched to the ISS, where they will experience conditions inside the Columbus module on the ISS in a special temperature-controlled Kubik facility. Once back on ground, researchers will examine the gene expression of the rotifers that were frozen in space to get a clear snapshot of what they were experiencing at the time at the molecular level.

In Part 2, the rotifers will be dried onto special agarose gels, where they will be strongly irradiated using an X-Ray machine. This will deliberately destroy their DNA but not kill them. Once in space, the dried rotifers will be reactivated with the lettuce juice and water mixture, exposed to space conditions and sent back to Earth in the frozen state. Eventually, researchers will examine the effects that their trip to space had on their ability to repair their own DNA, compared to ground controls.

The experiment is being designed and run by the University of Namur and result institute SCK-KEN of Belgium with the facility hardware built by Kayser Italia.

Kubik on Space Station

A miniaturised laboratory inside the orbital laboratory that is ESA’s Columbus module, this 40 cm cube has been one of its quiet scientific triumphs.

Kubik – from the Russian for cube – has been working aboard the International Space Station since before Columbus’ arrival in February 2008.

“Kubik hosts a wide range of life science experiments in weightlessness with minimal crew involvement,” explains Jutta Krause of the payload development team. “Research teams prepare their experiments and make use of existing or custom-built ‘experiment units’, which are each about the size of a box of pocket tissues.