European Satellite Could Discover Thousands of Planets

Princeton University and Lund University researchers project that the recently launched European satellite Gaia could discover tens of thousands of planets during its five-year mission.

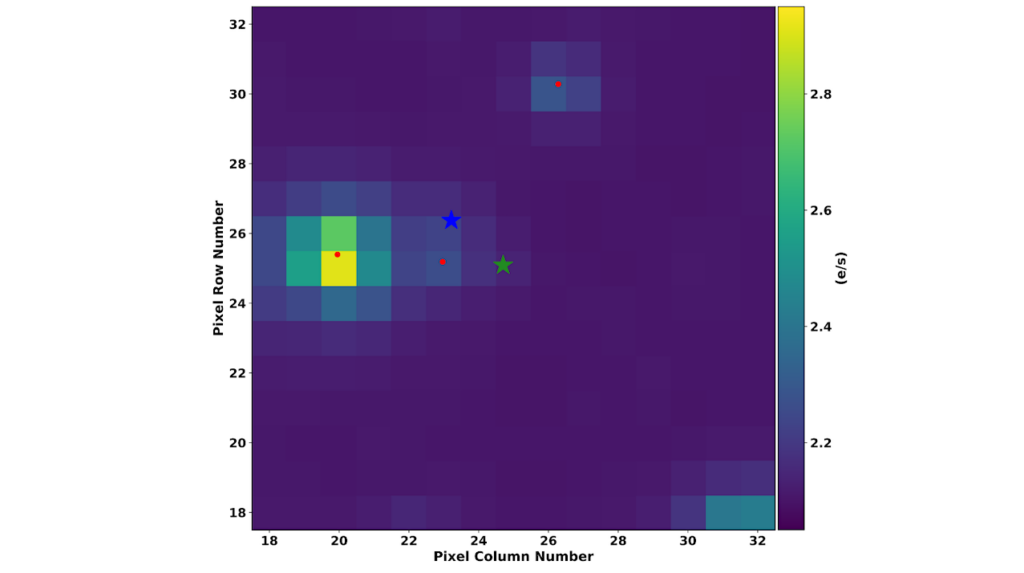

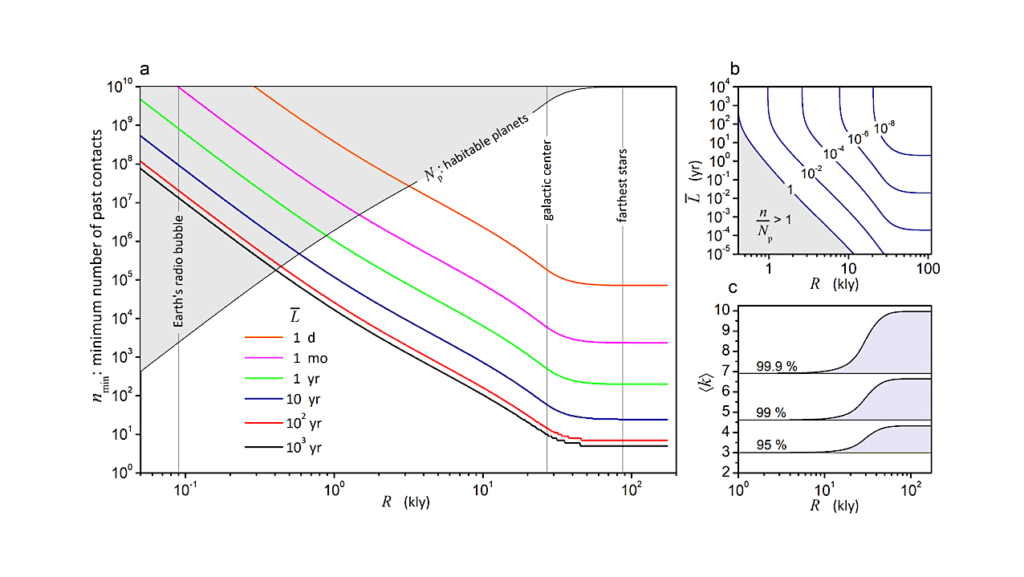

In this image, the colored portions indicate the number of observations Gaia would make of a particular part of the sky during its mission; the scale at the bottom indicates the number of observations from zero (purple) to 200 (red). The total number of observations of any part of the sky ranges from about 60 at low ecliptic latitudes to about 80 at high ecliptic latitudes, with a maximum of about 150-200 at intermediate latitudes. From these many different observations of each star, the highly accurate Gaia measurements will reveal the tiny star motion, or “wobble,” that results from any orbiting planet. (Image by Lennart Lindegren, Lund University)

A recently launched European satellite could reveal tens of thousands of new planets within the next few years, and provide scientists with a far better understanding of the number, variety and distribution of planets in our galaxy, according to research published today.

Researchers from Princeton University and Lund University in Sweden calculated that the observational satellite Gaia could detect as many as 21,000 exoplanets, or planets outside of Earth’s solar system, during its five-year mission. If extended to 10 years, Gaia could detect as many as 70,000 exoplanets, the researchers report. The researchers’ assessment is accepted in the Astrophysical Journal and was published Nov. 6 in advance-of-print on arXiv, a preprint database run by Cornell University.

Exoplanets will be an important “by-product” of Gaia’s mission, Perryman said. Built and operated by the European Space Agency (ESA) and launched in December 2013, Gaia will capture the motion, physical characteristics and distance from Earth — and one another — of roughly 1 billion objects, mostly stars, in the Milky Way galaxy with unprecedented precision. The presence of an exoplanet will be determined by how its star “wobbles” as a result of the planet’s orbit around it.

More important than the numbers of predicted discoveries are the kinds of planets that the researchers expect Gaia to detect, many of which — such as planets with multi-year orbits that pass directly, or transit, in front of their star as seen from Earth — are currently difficult to find, explained first author Michael Perryman, an adviser on large scientific programs who made the assessment while serving as Princeton’s Bohdan Paczyski Visiting Fellow in the Department of Astrophysical Sciences. The satellite’s instruments could reveal objects that are considered rare in the Milky Way, such as an estimated 25 to 50 Jupiter-sized planets that orbit faint, low-mass stars known as red dwarfs. Unique planets and systems — such as planets that orbit in the opposite direction of their companions — can inspire years of research, Perryman said.

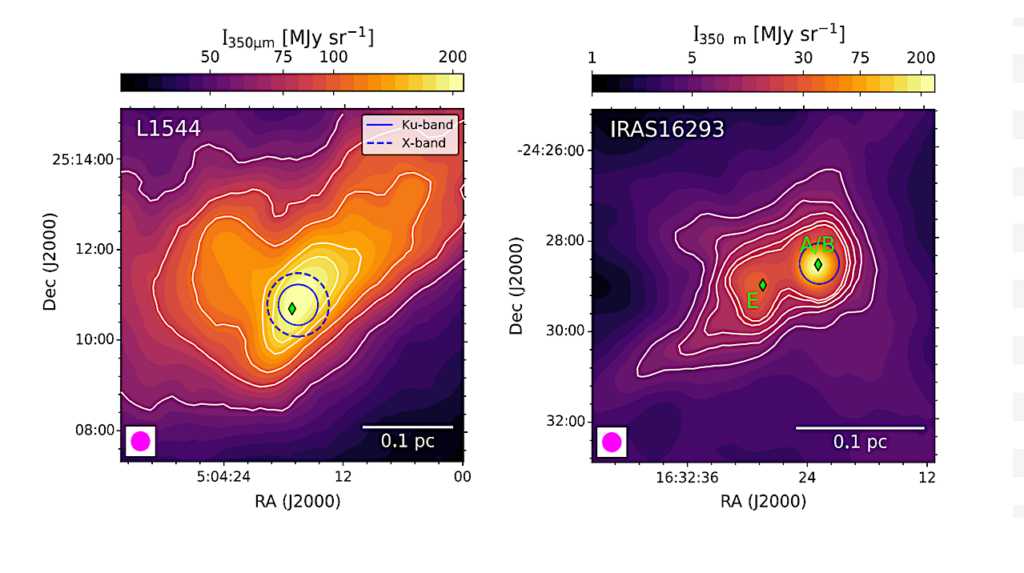

One of the main objectives of the Gaia mission is to establish the currently uncertain distance from Earth to various stars using high-precision triangulation, which would allow a much better understanding of the properties of the stars and the planets orbiting them. Of the 1,163 confirmed transiting planets, which pass directly in front of their stars as seen from Earth, there are 644 distinct host stars; less than 200 have accurately known distances from Earth. This image shows the distances from Earth (center) to the stars (black dots) of transiting exoplanets. The inner dashed circle has a radius of 100 parsecs (about 326 light years) with the middle and outer circles corresponding to 500 parsecs (1,630 light years) and 1,000 parsecs (3,260 light years), respectively. The cluster of points to the lower right represents the transiting planets discovered by NASA’s Kepler satellite. For each star, the straight lines extending from the circle indicate the current uncertainty of its distance from Earth. (Image by Michael Perryman)

“It’s not just about the numbers. Each of these planets will be conveying some very specific details, and many will be highly interesting in their own way,” Perryman said. “If you look at the planets that have been discovered until now, they occupy very specific regions of discovery space. Gaia will not only discover a whole list of planets, but in an area that has not been thoroughly explored so far.”

Ultimately, a comprehensive census allows scientists to more accurately determine how many planets and planetary systems exist, the detailed properties of those planets, and how they are positioned throughout the galaxy, Perryman said.

Perryman worked with Joel Hartman, an associate research scholar in Princeton’s astrophysical sciences department, Gaspar Bakos, an associate professor of astrophysical sciences, and Lennart Lindegren, a professor of astronomy at Lund University. Gaia is based on a satellite proposal led by Lindegren and Perryman that was submitted to the ESA in 1993.

Research on exoplanets has increased dramatically in the 15 years since Gaia was accepted by the ESA in 2000. The new estimate is based on a highly detailed model of how stars and planets are positioned in the Milky Way; more accurate details of Gaia’s measurement and data-analysis capabilities; and current estimates of exoplanet distributions, particularly those derived from NASA’s Kepler satellite, which has identified nearly 1,000 confirmed planets and more than 3,000 candidates. Crucial to conducting the assessment is the much-improved knowledge that now exists about distant planets, Perryman said, such as the types of stars that exoplanets orbit.

The first exoplanet was detected in 1995. Nearly 1,900 have since been discovered. Bakos, who focuses much of his research on exoplanets, launched and oversees HATNet (Hungarian-made Automated Telescope Network) and HATSouth, planet-hunting networks of fully automated, small-scale telescopes installed on four continents that scan the sky every night for planets as they transit in front of their parent star. The projects have discovered more than 50 planets since 1999.

“Our assessment will help prepare exoplanet researchers for what to expect from Gaia,” Perryman said. “We’re going to be adding potentially 20,000 new planets in a completely new area of discovery space. It’s anyone’s guess how the field will develop as a result.”

This work was partly supported by the National Science Foundation (grant no. 1108686) and NASA (grant no. NNX13AJ15G).

Read the article. Michael Perryman, Joel Hartman, Gaspar Bakos and Lennart Lindegren. 2014. Astrometric exoplanet detection with Gaia. Astrophysical Journal. Article first published to the arXiv preprint database: Nov. 6, 2014.