3-D Study of Comets Reveals Chemical Factory at Work

A NASA-led team of scientists has created detailed 3-D maps of the atmospheres surrounding comets, identifying several gases and mapping their spread at the highest resolution ever achieved.

“We achieved truly first-of-a-kind mapping of important molecules that help us understand the nature of comets,” said Martin Cordiner, a researcher working in the Goddard Center for Astrobiology at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. Cordiner led the international team of researchers.

Almost unheard of for comet studies, the 3-D perspective provides deeper insight into which materials are shed from the nucleus of the comet and which are produced within the atmosphere, or coma. This helped the team nail down the sources of two key organic, or carbon-containing, molecules.

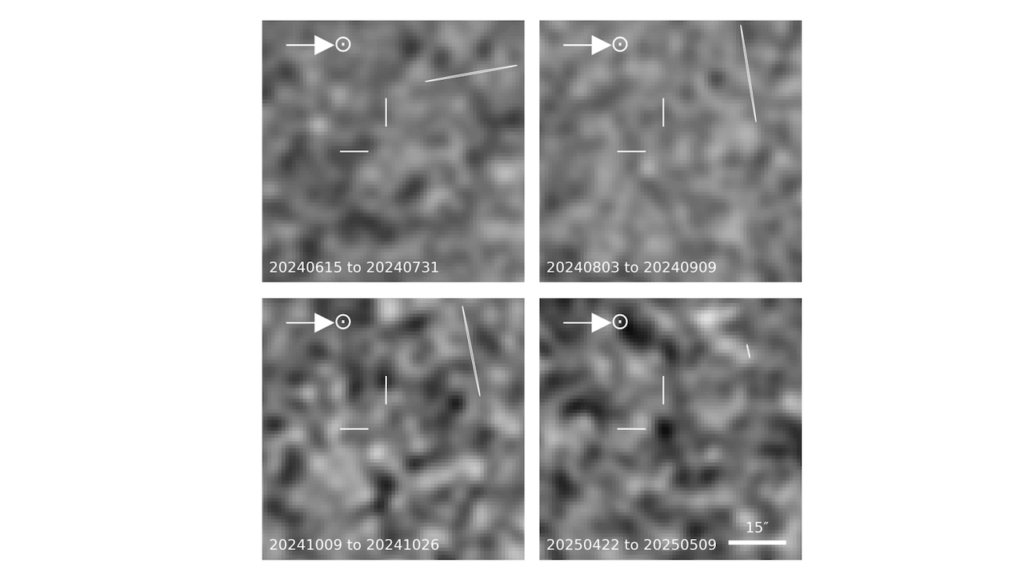

The observations were conducted in 2013 on comets Lemmon and ISON using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array, or ALMA, a network of high-precision antennas in Chile. These comets are the first to be studied with ALMA.

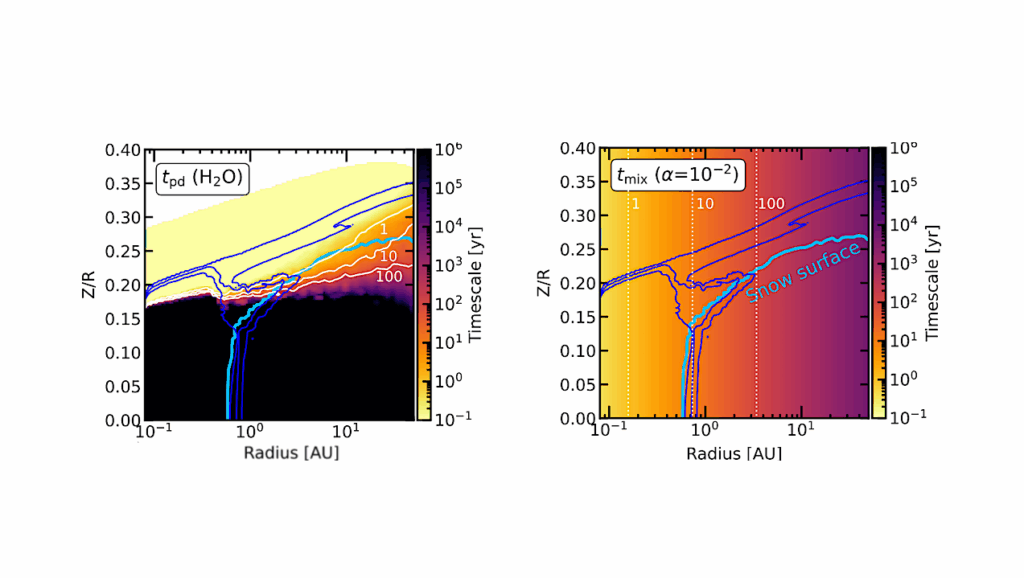

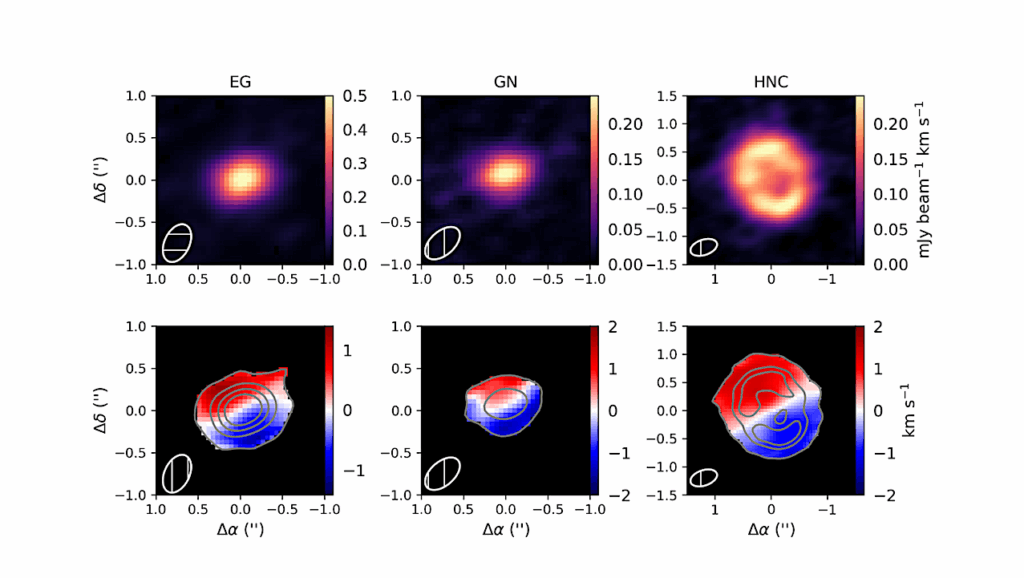

The ALMA observations combine a high-resolution 2-D image of a comet’s gases with a detailed spectrum at each point. From these spectra, researchers can identify the molecules present at every point and determine their velocities (speed plus direction) along the line-of-sight; this information provides the third dimension — the depth of the coma.

“So, not only does ALMA let us identify individual molecular species in the coma, it also gives us the ability to map their locations with great sensitivity,” said Anthony Remijan, a scientist with the National Radio Astronomy Observatory, one of the organizations that operates ALMA, and a co-author of the study.

The researchers reported results for three molecular species, focusing primarily on two whose sources have been difficult to discern (except in comet Halley). The 3-D maps indicated whether each molecule was flowing outward evenly in all directions or coming off in jets or in clumps.

In each comet, the team found that two species — formaldehyde and HNC (made of one hydrogen, one nitrogen and one carbon) — were produced in the coma. For formaldehyde, this confirmed what researchers already suspected, but the new maps contained enough detail to resolve clumps of the material moving into different regions of the coma day-by-day and even hour-by-hour.

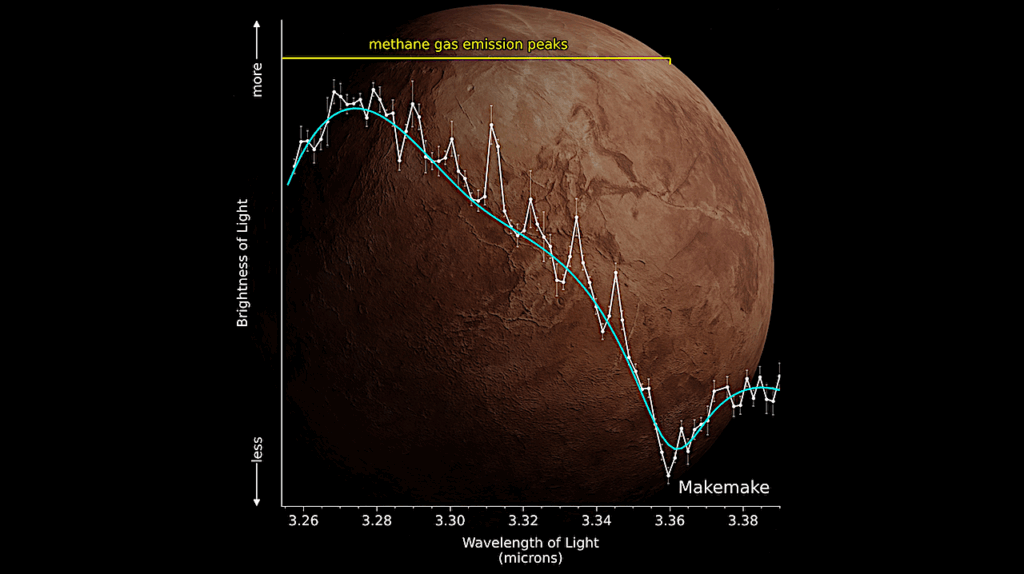

For HNC, the maps settled a long-standing question about the material’s source. Initially, HNC was thought to be pristine interstellar material coming from the nucleus of a comet, whereas later work suggested other possible sources. The new study provided the first proof that HNC is produced during the breakdown of large molecules or organic dust in the coma.

“Understanding organic dust is important, because such materials are more resistant to destruction during atmospheric entry, and some could have been delivered intact to early Earth, thereby fueling the emergence of life,” said Michael Mumma, Director of the Goddard Center for Astrobiology, and a co-author on the study. “These observations open a new window on this poorly known component of cometary organics.”

The observations, published today by the Astrophysical Journal Letters [http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/2041-8205/792/1/L2], also were significant because modest comets like Lemmon and ISON contain relatively low concentrations of crucial molecules, making them difficult to probe in depth with Earth-based telescopes. The few comprehensive studies of this kind so far have been conducted on bright, blockbuster comets, such as Hale-Bopp. The present results extend them to comets of only moderate brightness.