Viruses Hijack Deep-sea Bacteria At Hydrothermal Vents

More than a mile beneath the ocean’s surface, as dark clouds of mineral-rich water billow from seafloor hot springs called hydrothermal vents, unseen armies of viruses and bacteria wage war.

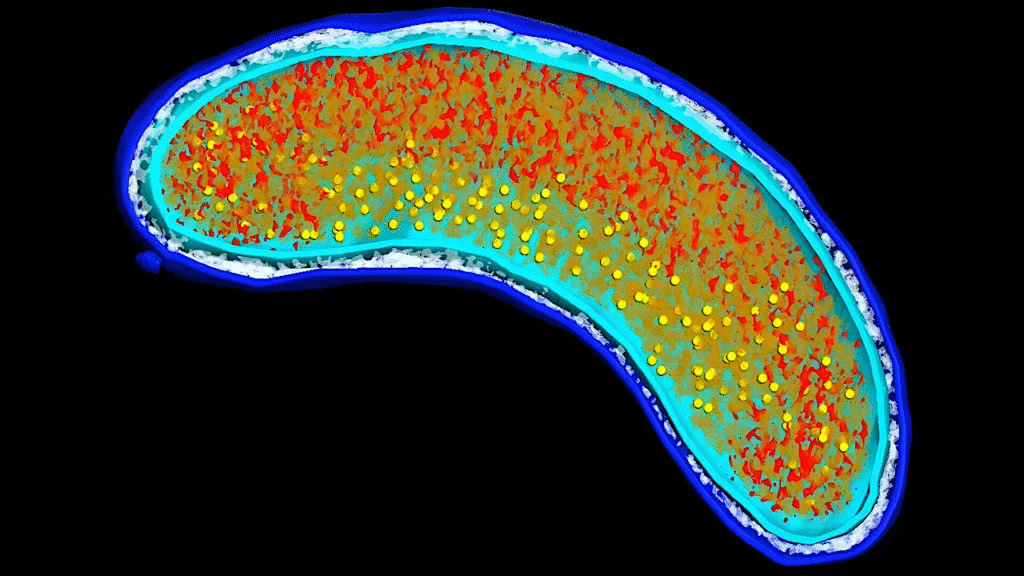

Like pirates boarding a treasure-laden ship, the viruses infect bacterial cells to get the loot: tiny globules of elemental sulfur stored inside the bacterial cells.

Instead of absconding with their prize, the viruses force the bacteria to burn their valuable sulfur reserves, then use the unleashed energy to replicate.

“Our findings suggest that viruses in the dark oceans indirectly access vast energy sources in the form of elemental sulfur,” said University of Michigan marine microbiologist and oceanographer Gregory Dick, whose team collected DNA from deep-sea microbes in seawater samples from hydrothermal vents in the Western Pacific Ocean and the Gulf of California.

“We suspect that these viruses are essentially hijacking bacterial cells and getting them to consume elemental sulfur so the viruses can propagate themselves,” said Karthik Anantharaman of the University of Michigan, first author of a paper on the findings published this week in the journal Science Express.

Similar microbial interactions have been observed in shallow ocean waters between photosynthetic bacteria and the viruses that prey upon them.

But this is the first time such a relationship has been seen in a chemosynthetic system, one in which the microbes rely solely on inorganic compounds, rather than sunlight, as their energy source.

“Viruses play a cardinal role in biogeochemical processes in ocean shallows,” said David Garrison, a program director in the National Science Foundation’s (NSF) Division of Ocean Sciences, which funded the research. “They may have similar importance in deep-sea thermal vent environments.”

The results suggest that viruses are an important component of the thriving ecosystems–which include exotic six-foot tube worms–huddled around the vents.

“The results hint that the viruses act as agents of evolution in these chemosynthetic systems by exchanging genes with the bacteria,” Dick said. “They may serve as a reservoir of genetic diversity that helps shape bacterial evolution.”

The scientists collected water samples from the Eastern Lau Spreading Center in the Western Pacific Ocean and the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California.

The samples were taken at depths of more than 6,000 feet, near hydrothermal vents spewing mineral-rich seawater at temperatures surpassing 500 degrees Fahrenheit.

Back in the laboratory, the researchers reconstructed near-complete viral and bacterial genomes from DNA snippets retrieved at six hydrothermal vent plumes.

In addition to the common sulfur-consuming bacterium SUP05, they found genes from five previously unknown viruses.

The genetic data suggest that the viruses prey on SUP05. That’s not too surprising, said Dick, since viruses are the most abundant biological entities in the oceans and are a pervasive cause of mortality among marine microorganisms.

The real surprise, he said, is that the viral DNA contains genes closely related to SUP05 genes used to extract energy from sulfur compounds.

When combined with results from previous studies, the finding suggests that the viruses force SUP05 bacteria to use viral SUP05-like genes to help process stored globules of elemental sulfur.

The SUP05-like viral genes are called auxiliary metabolic genes.

“We hypothesize that the viruses enhance bacterial consumption of this elemental sulfur, to the benefit of the viruses,” said paper co-author Melissa Duhaime of the University of Michigan. The revved-up metabolic reactions may release energy that the viruses then use to replicate and spread.

How did SUP05-like genes end up in these viruses? The researchers can’t say for sure, but the viruses may have snatched genes from SUP05 during an ancient microbial interaction.

“There seems to have been an exchange of genes, which implicates the viruses as an agent of evolution,” Dick said.

All known life forms need a carbon source and an energy source. The energy drives the chemical reactions used to assemble cellular components from simple carbon-based compounds.

On Earth’s surface, sunlight provides the energy that enables plants to remove carbon dioxide from the air and use it to build sugars and other organic molecules through the process of photosynthesis.

But there’s no sunlight in the deep ocean, so microbes there often rely on alternate energy sources.

Instead of photosynthesis they depend on chemosynthesis. They synthesize organic compounds using energy derived from inorganic chemical reactions–in this case, reactions involving sulfur compounds.

Sulfur was likely one of the first energy sources that microbes learned to exploit on the young Earth, and it remains a driver of ecosystems found at deep-sea hydrothermal vents, in oxygen-starved “dead zones” and at Yellowstone-like hot springs.

Dick said the new microbial findings will help researchers understand how marine biogeochemical cycles, including the sulfur cycle, will respond to global environmental changes such as the ongoing expansion of dead zones.

SUP05 bacteria, which are known to generate the greenhouse gas nitrous oxide, will likely expand their range as oxygen-starved zones continue to grow in the oceans.

In addition to Anantharaman, Dick and Duhaime, co-authors of the Science Express paper are John Breir of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Kathleen Wendt of the University of Minnesota and Brandy Toner of the University of Minnesota.

The project was also funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation and the University of Michigan Rackham Graduate School Faculty Research Fellowship Program.