Comparing Climates: From Earth to Exoplanets

A Comparative Climatology Symposium was held at NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC on Tuesday, May 7. The symposium focused on new approaches to climate research by highlighting the similarities and contrasts between the environments of the terrestrial planets Venus, Earth, Mars, and Saturn’s smoggy moon Titan. The symposium also included discussions about exoplanets, the Sun, and past, present and future space missions.

John Grunsfeld, Associate Administrator for NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, said that the upcoming James Webb Space Telescope will be able to make important observations of the atmospheres of exoplanets. He said JWST won’t be able to locate the exoplanets, only study them, but the recently selected TESS mission could act as a planet scout for JWST targets. It is estimated that TESS will discover around 300 Super-Earths, many in the habitable zone.

But the number one challenge, noted Grunsfeld, is figuring out the climate of our own planet.

Jim Green, NASA’s Planetary Science Division Director, said that one goal is to examine a variety of planetary bodies as a system, to see if there are trends or similarities. He also pointed out that from a planetary scientist’s perspective, climate change on our planet is not a new thing. “Earth’s climate has done nothing but change,” he noted.

Green said that three Earth-observing satellites will be launched this year, and they will help us better understand how the climate is currently changing and the implications that has for our planet’s environment.

David Grinspoon, holder of the first Baruch S. Blumberg NASA/Library of Congress chair in Astrobiology, talked about Mars’ “ferocious and interesting” meteorology, and how the martian global dust storms may help unravel what happened on our planet during the K-T extinction, when an asteroid hitting the Yucatan Peninsula is thought to have eradicated 75 percent of animals and plants on Earth, including the dinosaurs.

As for Venus, Grinspoon said scientists believe current-day volcanism on Venus is thought to be necessary to sustain the planet’s thick clouds. He added that the active surface has eradicated most ancient rocks, preventing us from easily understanding Venus’ early history.

Grinspoon also discussed the unique climate of Titan, noting that the methane cycle on this moon of Saturn is “like Earth’s hydrological cycle on steroids.”

Studying the climates of Mars, Venus, Titan and even exoplanets could help us refine our climate models of the Earth. However, Grinspoon said that “clouds are the biggest uncertainty in understanding the past of Venus and predicting the future of Earth.”

Tying climatology to astrobiology, Grinspoon said that our expectations of the other planets, in the absence of data, was that they’d be much more Earth-like than they really are. In the end we still haven’t found a planet quite like our own, although astronomers are honing in on exoplanets that should have habitable conditions. But, Grinspoon said, “It may be that conditions for life’s origin aren’t rare, but the hard part is the persistence of habitable conditions.”

Venus was a popular topic during the symposium. Roald Sagdeev, University of Maryland professor and former director of the Space Research Institute of the USSR Academy of Sciences, said during an overview of the Russian missions to Venus that “from the point of view of habitability, Venus is like having a dead body to study, which is of course very useful for learning anatomy.” David Crisp, Senior Research Scientist at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, said that sending weather balloons to Venus taught us a lot about atmospheric physics. And Roger Bonnet, Executive Director of the International Space Science Institute, said there was no chance for a big “flagship” mission to Venus, since the viewpoint among many was, “Who cares about clouds and wind on Venus, when we have so much of that on Earth? We want to see little green men!”

One participant noted the presence of “the Venus mafia” at the symposium, inferring that the focus on Earth’s “twin” planet had muscled out discussion of other places of interest. But in addition to studies of Venus and other terrestrial worlds, there was a talk about our Sun and its influence on “space weather,” and general discussions about refining climate models, defining habitable zones, and the importance of basic research. The participants seemed to agree that most importantly, planetary climate studies needed to be interdisciplinary, where scientists from different fields communicate and collaborate.

Michael Meyer, lead scientist for the Mars Exploration Program at NASA headquarters, also pointed out that we should never become complacent in our scientific understanding. For instance, he said that while climate models have not been able to make early Mars warm enough to sustain liquid water on its surface, the same can be true for models of the young Earth. And when it comes to understanding where a planet needs to reside in its solar system to be habitable — the so-called Goldilocks Zone where the temperature is just right for water to be liquid rather than ice or gas — he commented that “the approach [to the habitable zone] is very Goldilocks in that it’s almost a fairy tale.”

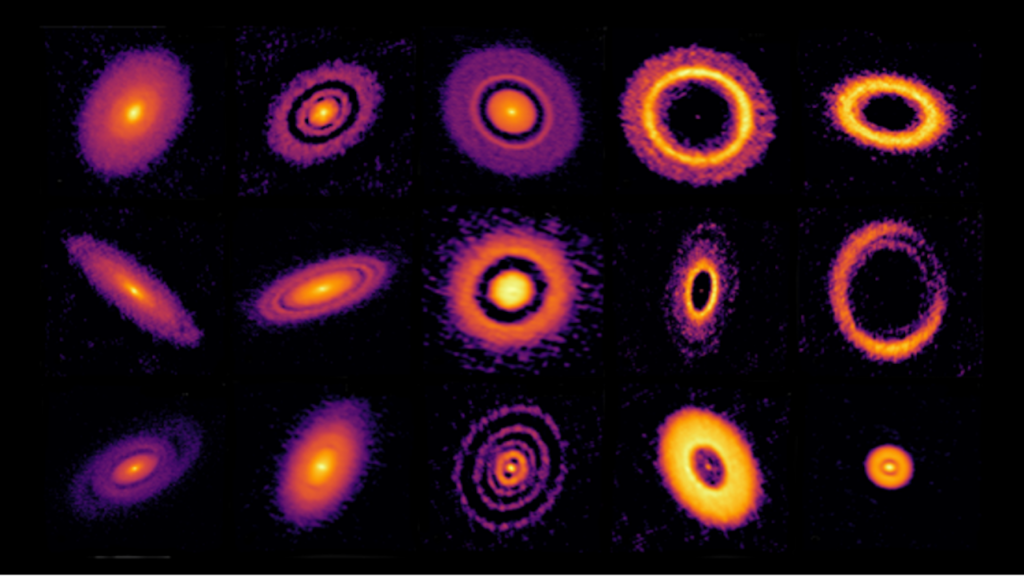

Finally, he noted, just when we thought we understood how planets are made, we discovered hot Jupiters and other unusual exoplanets which “turned all of our planet formation models on their head.”

“And that’s a good thing,” he added.

The featured speakers at NASA’s Comparative Climatology Symposium, titled “New Approaches to Climate Research,” were John Grunsfeld, Jim Green, David Grinspoon, Lori Glaze, Mark Bullock, Roald Sagdeev, Jack Kaye, Lennart Bengtsson, David Crisp, Roger Bonnet, Mark Marley, and Madhulika Guhathakurta.

– Leslie Mullen, Astrobiology Magazine