Did Phosphorous Trigger Blue Skies?

The evolution of complex life forms may have gotten a jump start billions of years ago, when geologic events operating over millions of years caused large quantities of phosphorus to wash into the oceans. According to this model, proposed in a new paper by Dominic Papineau of NAI’s Carnegie Institution of Washington team, the higher levels of phosphorus would have caused vast algal blooms, pumping extra oxygen into the environment which allowed larger, more complex types of organisms to thrive.

“Phosphate rocks formed only sporadically during geologic history,” says Papineau, a researcher at Carnegie’s Geophysical Laboratory, “and it is striking that their occurrences coincided with major global biogeochemical changes as well as significant leaps in biological evolution.”

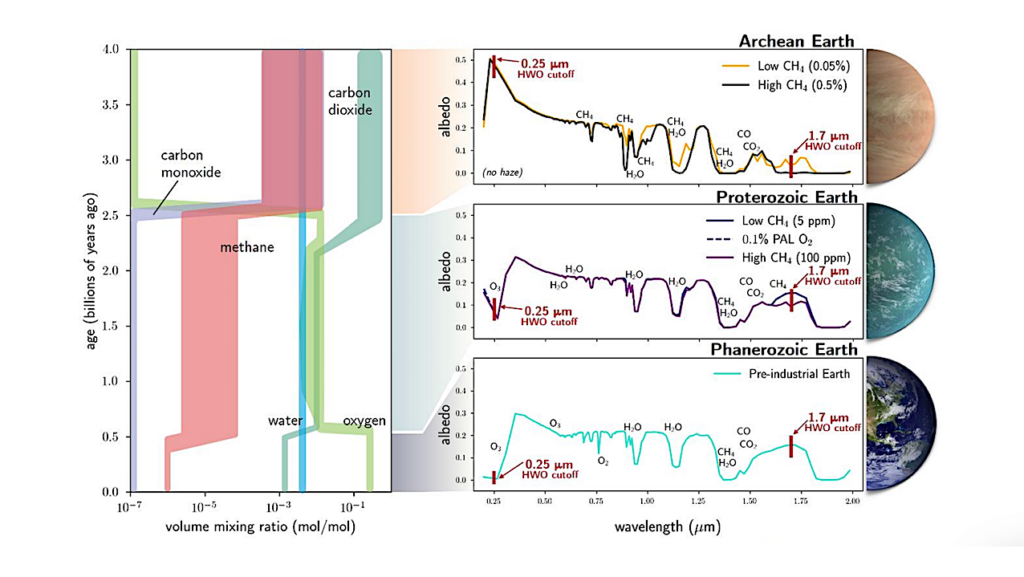

In his study, published in the journal Astrobiology, Papineau focused on the phosphate deposits that formed during an interval of geologic time known as the Proterozoic, from 2.5 billion years ago to about 540 million years ago. “This time period is very critical in the history of the Earth, because there are several independent lines of evidence that show that oxygen really increased during its beginning and end,” says Papineau. The previous atmosphere was possibly methane-rich, which would have given the sky an orangish color. “So this is the time that the sky literally began to become blue.”

During the Proterozoic, oxygen levels in the atmosphere rose in two phases: first ranging from 2.5 to 2 billion years ago, called the Great Oxidation Event, when atmospheric oxygen rose from trace amounts to about 10% of the present-day value. Single-celled organisms grew larger during this time and acquired cell structures called mitochondria, the so-called “powerhouses” of cells, which burn oxygen to yield energy. The second phase of oxygen rise occurred between about 1 billion and 540 million years ago and brought oxygen levels to near present levels. This time intervals is marked by the earliest fossils of multi-celled organisms and climaxed with the spectacular increase of fossil diversity known as the “Cambrian Explosion.”

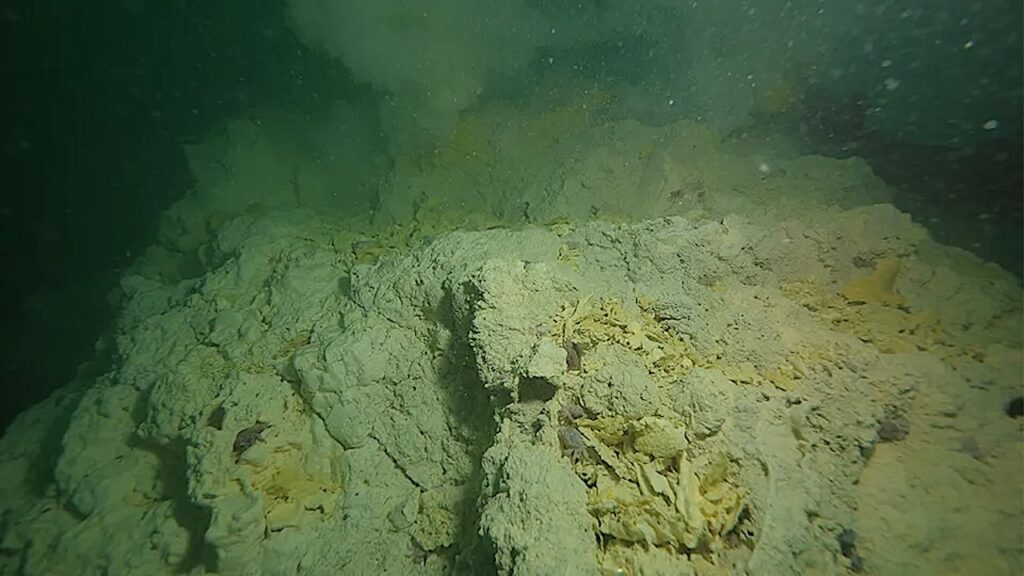

Papineau found that these phases of atmospheric change corresponded with abundant phosphate deposits, as well as evidence for continental rifting and extensive glacial deposits. He notes that both rifting and climate changes would have changed patterns of erosion and chemical weathering of the land surface, which would have caused more phosphorous to wash into the oceans. Over geologic timescales the effect on marine life, he says, would have been analogous to that of high-phosphorus fertilizers washed into bodies of water today, such as the Chesapeake Bay, where massive algal blooms have had a widespread impact.

“Today, this is happening very fast and is caused by us,” he says, “and the glut of organic matter actually consumes oxygen. But during the Proterozoic this occurred over timescales of hundreds of millions of years and progressively led to an oxygenated atmosphere.”

“This increased oxygen no doubt had major consequences for the evolution of complex life. It can be expected that modern changes will also strongly perturb evolution,” he adds. “However, new lineages of complex life-forms take millions to tens of millions of years to adapt. In the meantime, we may be facing significant extinctions from the quick changes we are causing.”

The research was supported by the Geophysical Laboratory of the Carnegie Institution for Science, Carnegie of Canada, and from the Fonds quebecois pour la recherche sur la nature et les technologies (FQRNT), NASA Exobiology and Evolutionary Biology Program, and the NASA Astrobiology Institute through Cooperative Agreement NNA04CC09A.

The Carnegie Institution (www.carnegiescience.edu) has been a pioneering force in basic scientific research since 1902. It is a private, nonprofit organization with six research departments throughout the U.S. Carnegie scientists are leaders in plant biology, developmental biology, astronomy, materials science, global ecology, and Earth and planetary science.

Founded in 1998, the NASA Astrobiology Institute (NAI) is a partnership between NASA, 14 U.S. teams, and six international consortia. NAI’s goals are to promote, conduct, and lead interdisciplinary astrobiology research, train a new generation of astrobiology researchers, and share the excitement of astrobiology with learners of all ages. http://astrobiology.nasa.gov/nai/

Astrobiology