Exploration, Science, and Art: A Book Review of Terra Antarctica and Driving to Mars

When it comes to exploration, there’s nothing like being there. Yet at some point, all explorers need to tell others what they have seen – as well as find a way to understand and recall the experience themselves. Exploration is pointless if it is not shared.

The first humans to explore new places would return home with verbal descriptions of where they had been and what they had seen. These stories would fade and lose accuracy with each retelling, yet they still had the power to inform and inspire. Over time, the invention of writing and art allowed these tales to take on a greater amount of clarity.

Soon, professional illustrators and then photographers would be enlisted. Accurate as these captured impressions were – they were just that: captured impressions – by someone else. Of course, the only way to get beyond that barrier is to go to these places and see things for yourself.

Yet even when someone makes the trip, they have to take in what they see before they can appreciate where they are. Some vistas and locations are so utterly alien and novel that explorers need a context with which to integrate what they see. And of course, even the most incredible adventure will fade over time in the mind of an explorer. As such recorded impressions also serve to aid one’s own memory of events in years to come.

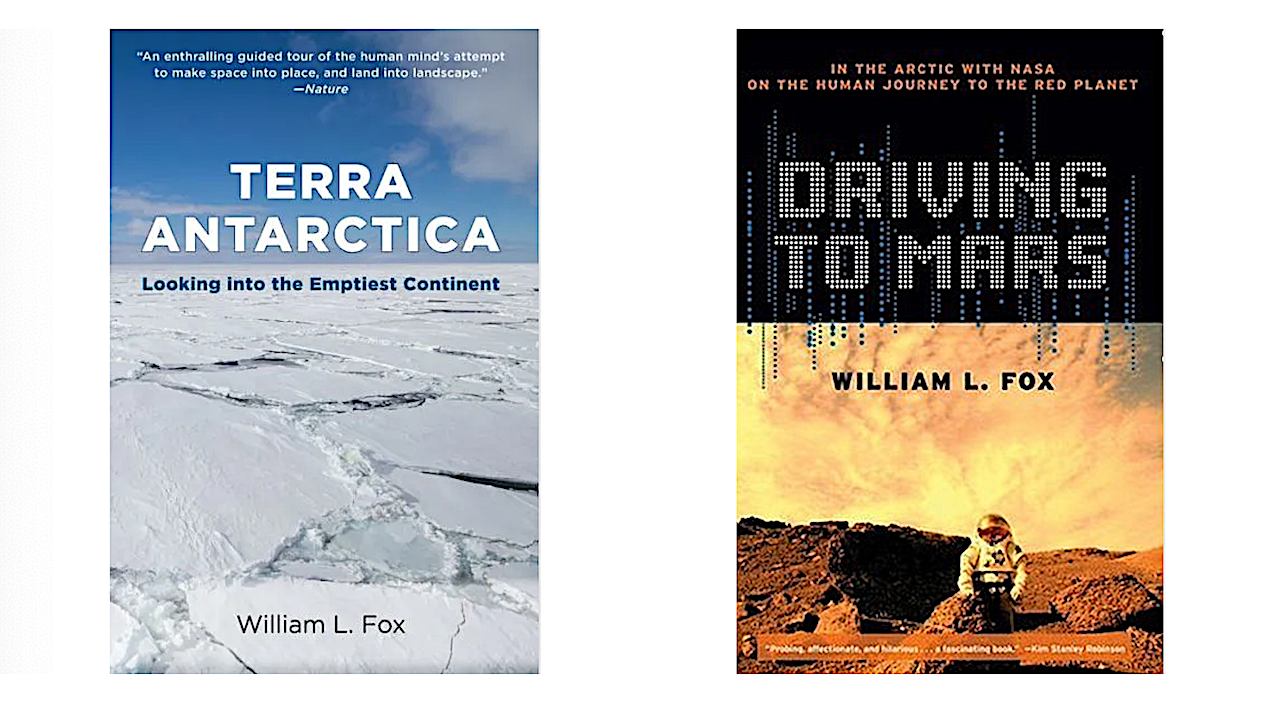

It is the process whereby explorers put new vistas and experiences into a context they can internalize – and then how these impressions are shared with others that fascinates author William Fox. In his two most recent books “Terra Antarctica” and “Driving to Mars” Fox recounts his own experiences – and those of others – at Earth’s two poles.

On one hand these books are the chronicles of a writer seeing things for the first time. Yet they are also books on polar science, astrobiology, planetary exploration, ecology – and art history. Weaved together as part travelogue – part natural history, these books are eminently readable. Moreover they should serve as a tutorial for anyone seeking to visit and explore other worlds.

Indeed, at times, as I was reading these books, I was reminded of the way the James Michener often opened his books so as to give readers a portrait of a certain place and time. Michener also sought to show how that place came to be over a broad canvas of history – covering thousands and (sometimes) millions of years. Fox also makes sure that you know who visited these places first – and how these first feats of exploration echo forward to the present day.

You also get a sense of the future in what Fox writes. It was little surprise to see such an influence given Fox’s friendship with author Kim Stanley Robinson and the referencing of his books “Red Mars” and “Antarctica”. People are learning as they explore. They also seek to apply what they have learned – here and off world.

In both of Fox’s books you find descriptions of people who are often quite ordinary – yet in many ways are extraordinary, placed in utterly alien and hostile locations. In some ways how they adapt is unusual – yet they also bring a surprising amount of their lives back in the real world with them.

Yet despite attempts not to spoil the very location they have come to study, these modern explorers transform these locations (or at least small portions) nonetheless. This is an issue that concerns Fox – and it will be an issue that will face us as we travel outward from Earth to explore and live on other worlds.

In Terra Antarctica, Fox relates two years of travels to the South Pole, McMurdo Station, and a variety of locations around the continent. He doesn’t just drop you into these locations, but rather provides historical and natural history backdrops so as to allow you to appreciate just how remote these places are and the dangers – and benefits – inherent in traveling to them.

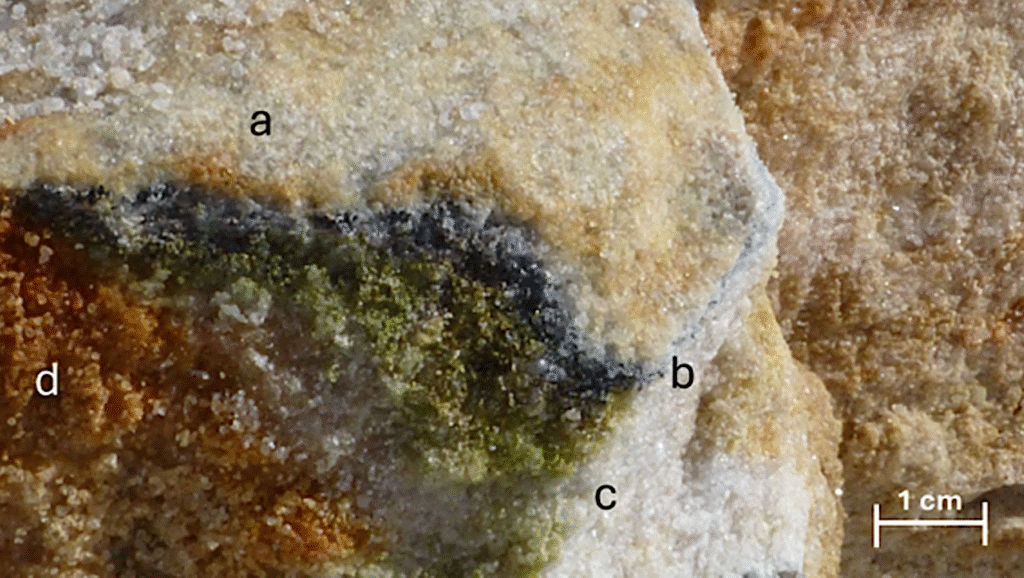

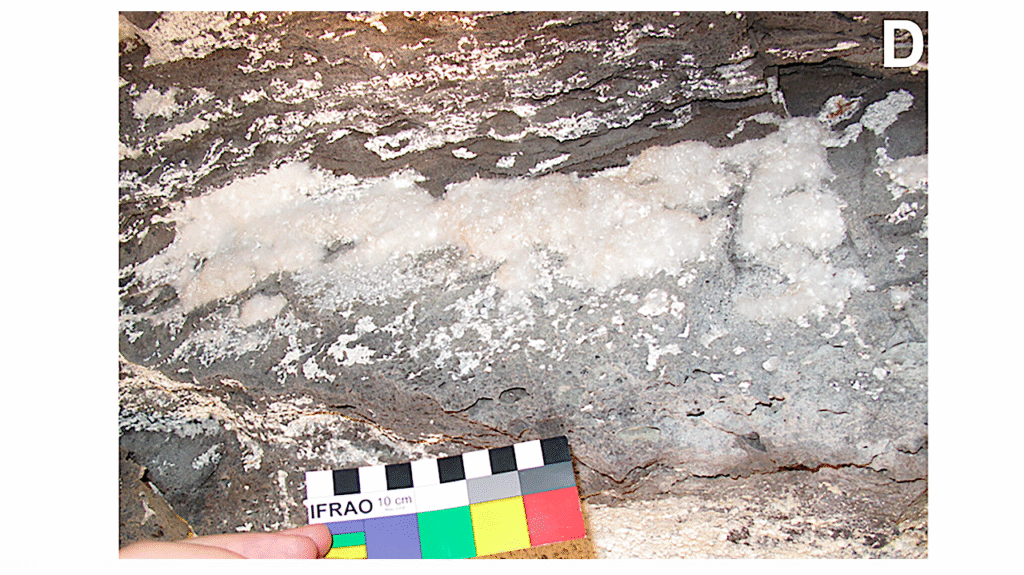

You get to go on field trips to the mysterious dry valleys where astrobiologists look for terrestrial analogs for conditions we may find on Mars – and whether we can expect to find life’s presence – or remnants when we get there. You also get to visit the preserved remnants of the great expeditions of the previous century.

As Fox reels out his travelogue, you also get a first hand description of what it is like to travel on land and by air across Antarctica and the slightly oddball human societies that you find when you get there. Perhaps his most endearing and fascinating depiction is life at McMurdo Station. As you read through his tales of quirky traditions and the ways that people adapt, you can almost start to envision what a permanent base on the Moon or Mars would be like a decade or so after being established.

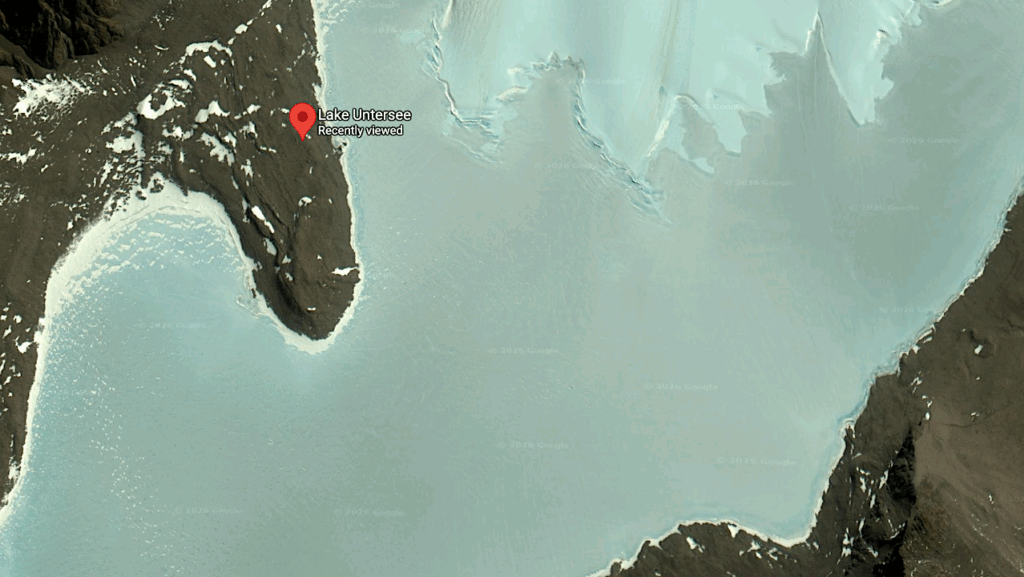

Yet, as pristine as Antarctica is – a place filled with novel, almost alien environments to study, it is often seen by many researchers as being “civilized” by virtue of the multiple bases and logistics system that has evolved over the last century. Some yearn for a place a little less developed to explore. There is such a location – one that is much more like the first bases we will establish on other worlds: Devon Island, located in the Canadian high arctic. This is the setting for much of Fox’s other book Driving to Mars.

As is the case with the Antarctic, the arctic offers many locations that are analogous to what we may find on Mars – and elsewhere in the solar system. In particular, Devon Island, home to the Haughton Mars Project (HMP) is such a location. While you can fly to the hamlet of Resolute Bay in an hour – and to full-fledged civilization in a few more hours, this logistics chain can be cut at a moment’s notice – and you are left with what you have on hand to survive. The veneer of connectivity to the rest of Earth is much, much thinner here. That is part of the value – and the allure.

HMP base camp is located next to the 38 million year old Haughton impact crater in a polar desert less than a thousand miles from the North Pole. Devon Island is largest uninhabitable island on Earth and is located in a region visited by many expeditions in the 19th century in search of knowledge – and the fabled Northwest Passage. Past, present, and future exploration co-exist in this place.

Visiting Devon Island evokes some truly alien impressions on all who visit. Having spent two one-month stints there myself, I speak from experience. There are places where your brain has no problem grappling with the idea that you are on Mars. It is there where I first met Fox who was researching Driving to Mars.

Driving to Mars makes a wonderful companion to Terra Antarctica. While both books cover similar and often overlapping themes, Driving to Mars is focused on this one location – and the natural history that makes it a good analog for Mars. As is the case with Terra Antarctica, you get to travel with Fox – on ATVs, modified Humvee rovers, and leap frogging in Twin Otter airplanes as he traverses the island. His travels take him to various locations where astrobiologists and geologists seek to understand this place on Earth – and yet place it into the broader context of comparative planetology. You also get to meet people who are trying to figure out how spacesuits need to be outfitted so as to allow people to truly explore the surface of Mars.

As you roam across Devon Island with Fox, you meet a variety of characters along the way (yes, I am one of them) who come from a variety of backgrounds. Everyone comes to this island every summer to not only study the place, but also learn how to conduct scientific and engineering research in a remote, hostile other worldly environment. All of these people also need to take something back from this place when they leave – their recollections being one of the most important.

Reading both books, you get a very good sense of place – not just what it is like to be there – but also what it is like for current visitors to walk in the footsteps of explorers who came before them – and (in the case of Devon Island) the indigenous peoples who explored the area thousands of years earlier.

The core theme of both books is how people take in what they see and then how they convey the experiences to others. Having spent two months myself doing precisely that in one of the locations Fox portrays (Devon Island), I have to say that he has aptly captured what it is like to be there – and the process whereby those experiences get interpreted and distributed.

As I write this review, new pictures are arriving on Earth from Mars. One set of imagery comes from the rim of Victoria crater as the Mars rover Opportunity seeks to find a way down inside. Meanwhile overhead the newly operational Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has begun sending back stunning high-resolution images of Mars. The first color image to be sent back shows the stunning vista of Victoria from above – including a recognizable speck on its rim – Opportunity itself. Yet as stunning and enticing as these images are – they are being sent back to us by a robot – without a human context. It can’t tell us what it is like to be there.

Right now we are exploring Mars by proxy using our amazingly resilient rovers. One day we will go there ourselves. Only then will we truly begin to know the planet in a human context. And when we do go there we will make the planet our own as we explore it, understand it, and then tell folks all about it back home. In so doing we’ll always be trying to strike a balance between what it is we have come to visit, what we bring with us, what we leave behind, and what we take back with us.

If you want to understand the people who are trying to figure out how to do this – and travel to remote locations on Earth in order to do so, then I heartily recommend both books.

Astrobiology