Kevin Hand’s Antarctic Journal 8 February 2005

Hello again from Antarctica,

Ok, well, I’m back at McMurdo Station. All went very well in the field – our instruments worked great, we collected lots of data, and had an amazing time exploring a phenomenally interesting and unique little nook on planet Earth. Now for the background on what exactly we’re doing.

I sent off my last email right before we were heading off via helicopter to our field site. The destination is called Battleship Promontory – it’s a beautiful band of sandstone towers nestled within the trans-Antarctic mountains and as you’ll see in the pics, the name suits the structures.

Pic 1. Battleship Promontory, Dry Valleys, Antarctica. Our camp can be seen (just barely) in the left-hand corner.

We were headed there to study the microbes that live within the rocks. Originally, no one thought life could exist in such a harsh, dry, cold environment, but back in the ’70’s Dr. Imre Friedmann, now at UW Seattle, inherited a rock sample from Antarctica that later led to him giving birth to the field of studying cryptoendolithic microbial communities (cryptoendolith – meaning within the pore spaces of rocks). Friedmann discovered complex communities of lichens (fungi + algae) and cyanobacteria thriving within the sandstone rocks of the Dry Valleys.

Much remains to be understood about how these communities live, die and ultimately modify the geological setting around them. On our team were two of Friedmann’s prodigies – Dr. Henry Sun of the Desert Research Inst. and Dr. Chris McKay, of NASA Ames. Their role was to help guide the rest of us through their well-trained eyes. As for the rest of us (8 people total), we had all been working on specially designed instruments that would help us study these life forms in the field. The idea was to bring the instruments to rocks, instead of bringing the rocks to the lab.

Pic 2: Me with our mid-infrared spectrometer. An instrument well suited for studying the mineralogy and organic chemistry of the rocks in this region.

Studying microbes is tricky in that regard, if you change the environment they often change what they’re doing. Thus, studying life in the lab often tells you one thing while in reality the little buggers may be doing something quite different in their home environs.

My role was primarily as an engineer working with Bob Carlson of NASA JPL on a set of three spectrometers (fancy prisms that split light and yield info about chemical composition) designed to study the mineralogy and organic chemistry of the rocks. Along with furthering our understanding of what makes these life forms tick, NASA is also interested in seeing how our field instruments perform.

The ultimate application would be for future robotic landers, a case where all of your instruments are sent off to a far and distant field with no one standing by to press the reset button if something goes wrong. At least two of our instruments had been proposed for the 2009 Mars Rover. Neither was selected, but we’ll likely try again during the next round.

So that’s the background, now for some stories and pics.

Pic 3: Helicopter taking off with part of our team and part of our several ton science load.

Flying machines will never cease to amaze me. They simultaneously seem to defy physics while at the same time serving as one of the most dramatic examples of physics beautifully at work. We boarded our helicopters, loaded with a few tons of gear, and headed across McMurdo Sound en route to Battleship Promontory.

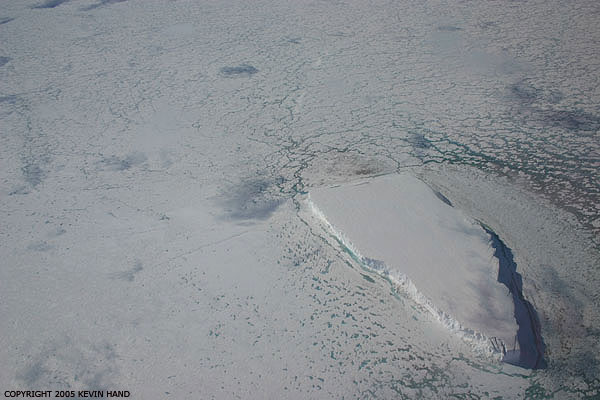

Pic 4: An iceberg trapped in the sea ice of McMurdo Sound. My guess is that the wall of this iceberg is somewhere in the range of 100 feet high.

Pic 5: The Trans-Antarctic Mountains, as seen from our helicopter.

After navigating through the labyrinth of mountains we came upon our destination and the helo pilots set us down. I personally, was incredibly excited, as were the others in my helicopter. But when we got out and had a chance to look around, I noticed a concerned look on Chris’ face. He and Pan and Henry had flown out in the first helicopter to scout out the location. When asked what the issue was, he pointed down the hill. We needed to be there. About 350 feet down a snowy talus field.

Pic 6: The view from “Upstairs”. All of our gear was dropped off on this plateau…but we needed to establish camp down below, in the sandstone rocks. The traffic of hauling our gear up and down inspired the name “Broadway”, given to the snow and rock gulley on the left, down which we hauled much of our gear. Our initial tent sites can be seen just past the shadow in the center of the picture.

The pilots had complications landing within the sandstone structures and so they dropped us up high on a flat plateau. That was all well and good – we could easily hike down and establish camp within the sandstone. The problem was our gear, in particular getting all of our heavy science gear down the hill. We spent the rest of the day shuttling essentials (tents, food, etc.) down to the desired campsite. As a result of all this traffic, our route up and down the mountain would later be named Broadway.

It took a few days, but eventually the helicopters were able to help us get our science gear down to the camp and before long we were up and running.

Pic 7: Help is on the Way. A helo lifts off with some of our gear as we pile on top of the rest of the gear to make sure it doesn’t get blown away.

Pic 8: Rho smiling after a close encounter with the helicopter. See pic 7 for ‘close’.

Conditions were beautiful and our science proceeded well. The pictures will give you a sense of this stunning landscape and some of the close-ups of the rocks will give you a sense of what we’re studying.

First, just look at the pictures of the cliffs and you see that the sandstone rocks are ‘painted’ with various colors.

Pic 9: Our camp at Battleship Promontory. After much hard work, we finally had a place we could call home.

Pic 10: View across the valley showing the cliff buttress that forms the base of the Battleship Promontory sandstone formation. The cliff is roughly 600 feet high.

Pic 11: A close up of one of the lichen-colonized sandstone rocks. The dimension of the picture is roughly 3 feet by 2 feet. Which colors are indicative of life beneath the surface? This is one of the many questions we sought to answer.

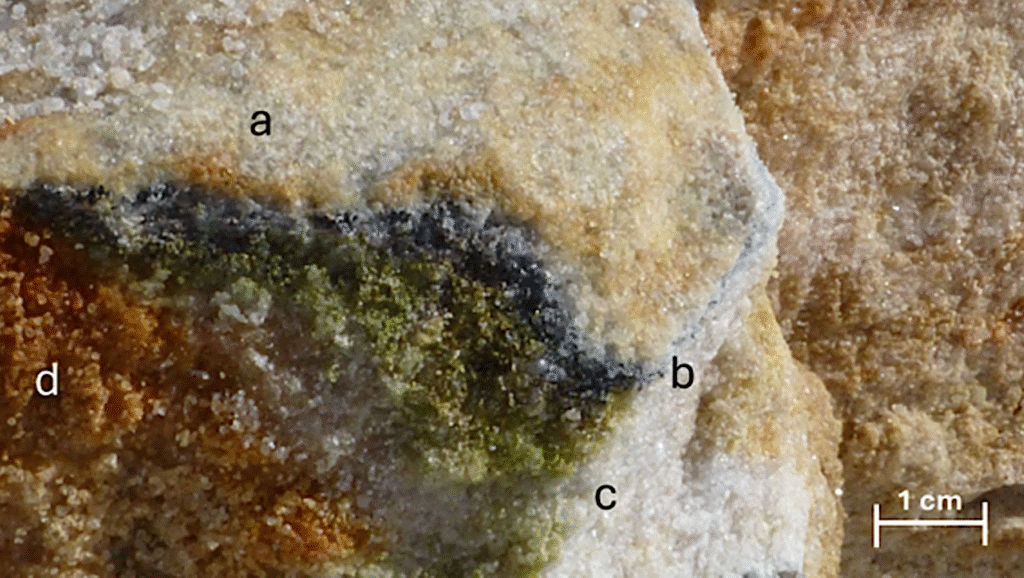

Upon closer inspection you’ll see that the surface of some of these rocks are covered by a mosaic of browns, yellows, oranges, and reds. These colors result from both inorganic (non-biological) and biological chemical reactions. The bugs (microbes) within the rocks play a role in how the rocks look and how they weather. Someone like Henry, who has a trained eye, can look at the colors and discern where the microbes live beneath the surface. Part of our technical challenge was to see if our instruments could accomplish the same task. In this particular picture, you can see some black spots around the edges of some of the rock flakes. This is the lichen poking out from under the rock. It has probably become exposed because a chip recently fell off the rock as a result of wind erosion.

Pic 12: A cross section view of one of the rocks we analyzed. Our mid-infrared spectrometer can be seen at top. The coloration of the interior of the rock results from an interaction of the lichen community (thin black line near the top of the rock) with iron that is deposited at the surface and transported to the interior (bright red line).

Pic 13: Through a hand-lens (magnification 15x) one can see the dark spots of microbes inhabiting the regions between the clear sandstone crystals.

Henry, Bob, and I worked together on our mid-infrared, near-infrared, and visible spectrometers. We had the system set up so we could be running 24 hours a day, collecting as much data a possible. We set up a rotating sleep schedule so that someone was always awake to check on the instruments and to make adjustments when needed. We had a bit of troubleshooting here and there, but overall things worked as planned. Bob and I had spent two days testing out our system in a walk-in freezer at JPL and that was proving to be time well spent.

Pic 14: Me, Henry, and Bob (L-R) during one of our ‘late-night’ hikes around the fascinating formations of Battleship Promontory.

Pic 15: Bob and Henry enjoying a warm drink in our ‘BP Cafe’ after working hard to get the instruments up and running.

Our biggest limitation was power – we had solar panels but we were expecting more of them from the supply shop at McMurdo. The team had a small generator and that worked well until the oil dried up. Then we had to resort to really optimizing for every possible photon we could collect from the sun. Henry, Bob, and I grabbed the extra solar panels used to recharged to the communications equipment and added them to our array. We lashed together some bamboo poles and set up shop on top of a small hill near the campsite. When we were done, our newly christened ‘solar city’ on top of Sun Hill looked like something straight out of Gilligan’s Island.

Pic 16: Solar City on top of Sun Hill, named both for the star that powered our instruments and the talented biologist, Henry Sun, who was on our team and who has done so much work in the area.

Recall that since we’re at ~77 degrees south, at this time of year the sun never sets. Thus, as the sun made its circle around the sky we would periodically go up to the hill and rotate our array. For a few hours each day the sun was eclipsed by the big mountain behind our camp, but other than that we had plenty of sunlight on clear days.

The rest of the team seemed to keep pretty standard hours, while Bob, Henry, and I got into this fun cycle of trading shifts during the day and then around 3 or 4 in the morning the three of us would set the instrument on autopilot and head off for a hike to explore some yet to be explored region of the mountainside. This lead to many great discussions, discoveries, and views (e.g. see meadowscliff.jpg). Hiking around the sandstone formations gave one the sense of hiking around some ancient ruins with meandering corridors and teetering towers. The silence and serenity is stunning. The cold air clears the mind. The timeless landscape is incredibly humbling, but invigorating.

More in a few days…

Pic 17: Me with the sandstone formations in the background and Mt. Morrison in the far background.

Astrobiology