Keith Cowing’s Devon Island Journal – 31 Jul 2002: Culture Shock and Flight Delays

I awoke this morning to a slight amount of disorientation: being inside a building in a bed with a TV in front of me – not in a noisy tent in an arctic desert. Yes, I was back in Resolute – the next best thing to “civilization”.

This was a familiar experience. Almost exactly 11 years ago to this day I awoke in my small condo in Virginia. Barely 24 hours earlier I had been asleep atop an 800 tall sheer pillar called the “Petit Grepon” in Rock Mountain National Park. We had just completed a multi-hour climb to get there. The summit was only a few feet across. When I awoke back home, for a moment my brain told me that I was sleeping in that same precarious location. It was exactly that feeling that I experienced this morning.

The entertainment and computer room at the Co-op where we sat and waited for our flights in and out of Resolute

I made certain to lavish myself with a breakfast composed of whatever they had to offer at the Co-op. The four of us (George Martin, Camp Doctor, Darlene Lim, Limnologist. Nesha Trenholm, geology undergrad and myself) were the only ones here. As such, the cook made what ever we wanted.

Just as I was all packed and ready for the trip from Resolute to Ottawa, we got word that the flight was cancelled for the day. I would later find out that the jet had flap problems. It was OK to land it at Iqualut and its larger airstrip – but they did not want to risk landing it on the shorter, gravel runway at Resolute. Besides, they did not have the maintenance infrastructure in Resolute to fix the flaps.

As such, I had another day to spend in Resolute. I managed to avail myself of the wonderful weather and get some nice photos of Resolute and the stark, but stunning, landscape that surrounds it. Resolute Bay was still partially frozen with larger chunks of ice here and there. All I had to do was frame the photo and snap – the scenery did the rest.

We stayed in the brown building on the left. On the right is a Co-op garage

The rest of the time I spent online tending to my various websites and catching up on other things that had slipped in the month I had been in Nunavut. Meals suddenly became a chance to reacquaint myself with familiar things. For some reason I found myself living on BLTs for the next several meals. I have no explanation whatsoever why this food fetish came upon me.

Technology not withstanding, being in this part of the world is a new experience. I can watch local news, weather and sports from Los Angles, Detroit, or Toronto via satellite. I can even see what the daily lucky local Lotto numbers are – yet I feel quite distant from the real world (or at least the one I live in).

On Devon Island, sans the TV, the feeling is much more pronounced. Our communication links were actually more sophisticated than what I used in Resolute and not that much different (in terms of speed) from what I have in my office at home – with one important exception: the cost of providing these services.

Resolute Bay. A Coast Guard ship is anchored offshore.

If I needed to, I could have made a phone all home to my wife via either an Iridium Phone, MSAT, or various Internet telephony software. I had no real reason to do so other than to say hello – and I had other ways to do that. Indeed, my wife and I interacted many times a day in near real time. Using AOL Instant Messenger (AIM) , I could chat with my wife at work, or after her commute home, as she sat and watched TV or did chores at night. There was a noticeable lag in the performance of AIM, but it was not at all cumbersome and I soon came to ignore it. No worse than a day of slow Internet service back home.

One of the things I thought about a lot while on Devon Island was how I would function if this were a real space mission on Mars. There will likely be advances in software and communications technology by the time we get around to sending people there. Yet I think that Internet messaging or chat software would work just fine for my wife and I – were I to find myself on such a mission. Augmented with occasional pictures, some sound files, and some movie clips, the interaction is enough that people can keep tabs on each other – in various approximations of real time.

Seal jawbone lying on the beach

The only major exception (other than bandwidth constraints) would be lag time depending on where Mars and Earth were with respect to one another. Still, a 20-minute lag (times 2) would still allow some semblance of a conversation. Whether this would be email or chat software I’ll will leave to someone else.

My wife tells me that being able to see images of me on Devon Island was good. By coincidence, one of our live webcams was positioned in the Comm Tent such that I was in the picture whenever I was in the tent – although the frequent heavy winds did cause the camera mount to walk around a bit and re-point the camera. With a 5-minute refresh rate, she could get an idea of what I was up to – including my apparent weight loss (when I was caught leaning back) and the Hamilton Sunstrand guys and their concept Mars Spacesuit being put onto various scientists.

But this may not work for everyone. One person in Base Camp made daily Internet calls home to his wife. Another used emails. Another (like me) used instant messaging to his extended family. I suppose before we send people off to Mars, we’ll need to place them in a situation like Devon Island and see how they handle the separation.

We’re so far north that people point their satellite dishes at the ground to get backscatter

Given all of the Internet access and interaction I had with my wife and friends, I never felt at all isolated. Given the large size of our camp (almost 30 people) and the new faces that would arrive every week, I never felt like I was forced to endure any one person or their habits for an undue period of time.

On a Mars mission, of course, there’d be a small group – and they’d be together for a very long time. My advice, as mentioned above, is to make sure the team works together in a variety of isolated locales on Earth (and in space first). Moreover, any mission to Mars should set aside considerable thought and planning to the communication capabilities of the mission. A crew that feels like they are still attached to their families back on Earth – and can share the experience with them is, in my estimation, one of the easiest ways to assure mission success from a human mental health perspective.

My wife saw me bundled up on the webcam and sent me a note “you look cold”

After several hours of work, and yet another BLT for dinner, I made a point of simply relaxing. For some peculiar reason, the satellite television seemed to be all Star Trek – all the time. Being a Star Trek fan, that was just fine with me.

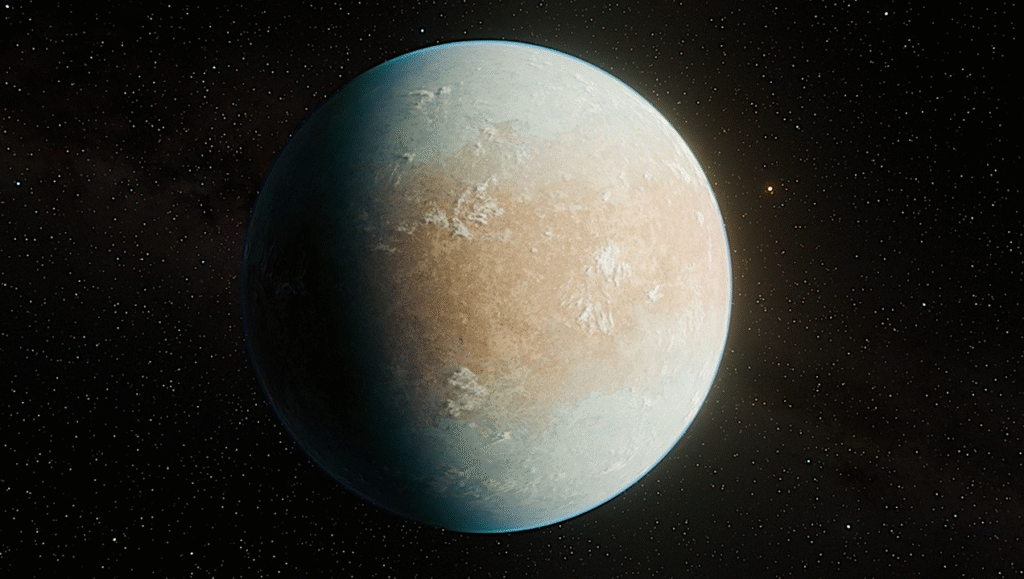

Mars crews will need to see the folks back home too (NASA image)

Astrobiology